There’s a new 360o view of the National Aviary penguins on the Post-Gazette website. The P-G uses a special video camera…which the penguins jump up on. You can hear them chirr at it. Very cool!

Monthly Archives: February 2011

Courtship Flights

In February and March we see peregrines court at the nest on the falconcams but it’s much more exciting to watch these birds in the air.

In the weeks leading up to egg laying the pair engages in courtship flight. It’s a spectacular way to get in tune with each other and show off their flying prowess.

Here’s what you’ll see:

The male peregrine begins by circling high above the cliff. Sometimes he travels in an undulating pattern or a figure eight. His mate will rise up near him and circle high as well. Soon they’ll begin to play in the air and may roll upside down or make a big Z in the sky. Sometimes this playing looks dangerous because one will dive on the other as if he or she were prey — but of course the dive misses. Sometimes the male pretends to carry food and the pair does a mock prey exchange in the sky.

Back and forth, soaring high and diving low, their flight is breath-taking. Not only does this activity cement their pair bond but it advertises to any passing peregrine that their nest cliff belongs to them.

Eventually the pair zooms to the cliff and lands near the nest.

If you’re watching the webcam you’ll see them appear on camera at this point … but you’ve missed the big show!

(photos by Chad+Chris Saladin)

Vigil

At the Cathedral of Learning, Dorothy spent last night perched at the nest. Here she is sheltering from this morning’s pre-dawn thunderstorms.

As far as I know female peregrines don’t roost at the nest unless they’re ready to lay eggs in a couple of days.

However my knowledge of this is very limited. I only learned about it last year when we were able to see the nests at night for the first time.

It seems too early for eggs, but who knows. We’ll just have to wait and see what this means.

(photo from the National Aviary snapshot camera at University of Pittsburgh)

Open Wide!

What is this wood stork doing?

Is he yawning? Is he calling to a passing bird? Is he about to cast a pellet? Do wood storks even have pellets?

I checked Cornell’s Birds of North America Online and they said of the wood stork, “No information on pellet-casting.” However, wood storks eat fish so they might need to regurgitate fishbones.

I prefer to think he’s smiling for the camera. 😉

(photo by Chuck Tague)

Galling

Now that we’ve had a hint of spring it’s tempting to look for signs of it in the garden even though our calendars and today’s weather still say “February.”

Pussy willows are a good place to look because they’ll soon have fuzzy buds, soft as kitten fur. But don’t be surprised if you find some odd growths on the willow branches. Here’s one of them.

This is a willow beaked-gall caused by the Willow Beaked-gall Midge, a fly as small as a gnat. The gall is a malformed willow growth, the beaks are the willow’s buds poking out of the gall.

Nearly a year ago the female Willow Beaked-gall Midge laid her eggs in the willow buds as they began to open in the spring. The chemicals produced by her eggs and by the larvae that hatched from them caused the willow’s cells to grow into this misshapen ball.

At first the gall was green but later it hardened and turned red. Meanwhile it houses the Willow Beaked-gall larvae over the winter. In early April they’ll emerge as adults to start the whole process over again.

These galls don’t hurt the plant but they sure are ugly.

(photo by Marcy Cunkelman)

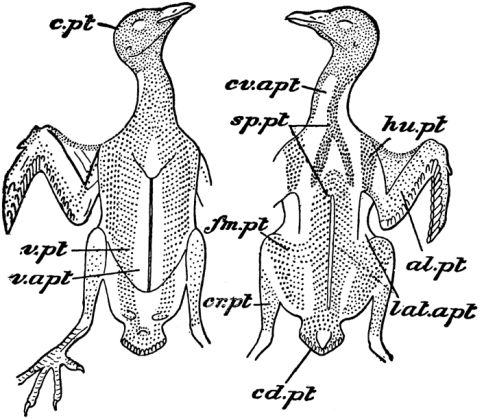

Anatomy: Feather Tracts

Fifteen months ago I started this Friday series on bird anatomy as a project for the winter of 2009-2010. Now, 67 entries later, I’m declaring that winter is over and freeing up my Fridays for time to write about spring flowers, bird migration, and peregrines. This is the last regularly scheduled anatomy lesson but it’s not the last blog I’ll ever write on anatomy. Who knows? I might change my mind and restart the series in July. 😉

Today’s topic was suggested by Tony Bledsoe when I posted a photo of a warbler whose belly feathers were blown aside to expose its fat reserves. We can see birds’ belly skin because their feathers are arranged in tracts.

Unlike mammals whose hair sprouts uniformly from the skin, most birds’ feathers sprout in tracts called pterylae with bare patches of skin between them. Pterylae are like forests of feathers and that’s what the word means: pteron is “feather,” hulé is “forest.” The bare patches between them are called apteria: “without feathers.”

Shown above are the pterylae of a rock pigeon. You can see from the illustration that there are apteria on the neck and belly but we rarely see a bird’s bare skin because their feathers fan out to cover their bodies.

It’s interesting to realize that the bare spot on the belly (arrow points to v.apt) is a good beginning toward a brood patch for incubating eggs and brooding young.

Some birds are exceptions to this rule. Penguins’ feathers sprout uniformly across their bodies. You can’t blow on a penguin’s belly and see its skin.

I’ll bet the lack of pterylae explains why penguins don’t use their bellies to incubate their eggs. They use their bare feet!

(clip art from the Florida Center for Instructional Technology (FCIT) at University of South Florida. Click on the image to the see the FCIT clip art library.)

White Winged Gulls

February gull watching was a bust here in Pittsburgh.

Yes, we’ve had some gulls, but in most years harsh weather freezes the Great Lakes and pushes the waterbirds south. This makes for spectacular (and very cold!) birding at the Point in February when the “white winged gulls” visit our three rivers and roost overnight at the head of the Ohio.

But it didn’t happen this year. The rare gulls stayed north or they went somewhere else.

This glaucous gull skipped the Great Lakes and went to Florida where Chuck and Joan Tague saw it during their annual North American Shorebird Survey in Volusia County on February 4th.

See what I mean about white wings? Here in Pittsburgh we were hoping for Iceland and Thayers gulls, too.

Oh well. We can’t have both. It’s either a harsh winter with white winged gulls or a mild winter without them.

What should we should hope for next year?

(photo by Chuck Tague)

Foxtail Grass

This grass is aptly named because its seed head resembles a fox’s tail.

Foxtail grass can be a weed or an ornamental depending on your point of view. The small version (Setaria glauca) is annoying in the “perfect lawn” but giant foxtail (Setaria magnus) is quite beautiful with its large fuzzy tufts that hold seeds at the base of the hairs.

You don’t have to cultivate foxtail grass. It grows easily by the side of the road and in waste places. And without any effort it will grow in your lawn.

Foxtail grass is in the same genus as cultivated millet. I’ve often watched house sparrows jump up to pull seeds from the plumes of foxtail grass in my backyard. Oddly, they refuse to eat the millet in mixed birdseed — they literally throw it on the ground.

Hmmm… Is that where my foxtail grass came from?

(photo by Marcy Cunkelman)

False Advertising!

Only four days ago we had clear skies and 66o.

Spring was here, I shed my coat and took a long walk, enjoying the new season, making plans for spring activities. Oh, how happy!

Four days ago the weather forecast said it would be colder today but it didn’t sound bad. Then yesterday morning the weatherman predicted 2″-4″ of snow. By afternoon he’d changed his mind and was calling for 3″-5″ starting at 6:00pm.

Instead the snow started at 4:00pm and fell heavily, snarling rush hour traffic. I didn’t have my snow boots on (it was spring, wasn’t it?) and I didn’t want to walk far, so I waited for the bus that stops 300 feet from my house.

It never came. After 50 minutes I took the bus that stops a half mile from my house. Grrrr!

Our official snow total is 8.4″ at the airport. As you can see, there are 8 inches in my back yard.

I’d have nothing to gripe about if there hadn’t been so much false advertising.

(photo by Kate St. John)

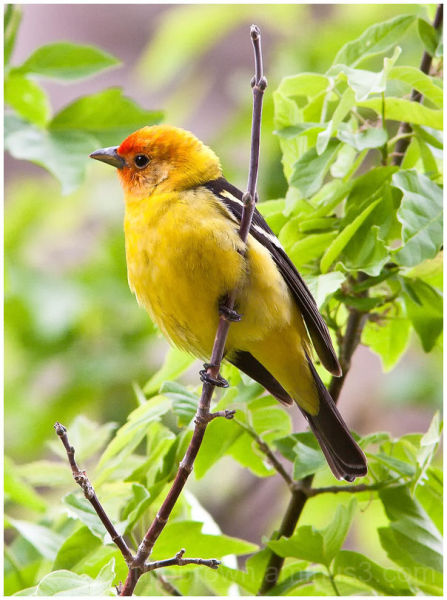

Not Here, Not Now

This beautiful bird is a male western tanager.

Because I don’t go west very often, I’ve only seen one once — at Donner Pass in the Sierra Nevadas. At the time it was July and he was in breeding plumage with a completely orange-red face.

Western tanagers (Piranga ludoviciana) are truly western birds. If you draw a line down the middle of North America they’re always west of it (the 104th meridian). Even then, they spend most of the year outside the United States in southwestern Mexico, south to Costa Rica.

Western tanagers breed in North American forests and travel farther north than any other tanager, ranging all the way to Canada’s Northwest Territory. The birds who travel that far have such a long trip that they spend only two months on their breeding grounds.

Right now, except for a small winter range in coastal southern California, these birds are still in Mexico and Central America. They’ll head north with the main body of spring migrants, arriving at this latitude in late April or early May. It’s something to look forward to out west, just as we look forward to scarlet tanagers in the east.

But, alas, it’s still winter. The tanagers are not here, not now.

(photo by Julie Brown)