Fifteen months ago I started this Friday series on bird anatomy as a project for the winter of 2009-2010. Now, 67 entries later, I’m declaring that winter is over and freeing up my Fridays for time to write about spring flowers, bird migration, and peregrines. This is the last regularly scheduled anatomy lesson but it’s not the last blog I’ll ever write on anatomy. Who knows? I might change my mind and restart the series in July. 😉

Today’s topic was suggested by Tony Bledsoe when I posted a photo of a warbler whose belly feathers were blown aside to expose its fat reserves. We can see birds’ belly skin because their feathers are arranged in tracts.

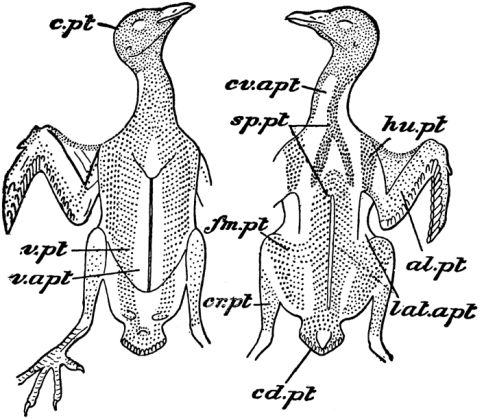

Unlike mammals whose hair sprouts uniformly from the skin, most birds’ feathers sprout in tracts called pterylae with bare patches of skin between them. Pterylae are like forests of feathers and that’s what the word means: pteron is “feather,” hulé is “forest.” The bare patches between them are called apteria: “without feathers.”

Shown above are the pterylae of a rock pigeon. You can see from the illustration that there are apteria on the neck and belly but we rarely see a bird’s bare skin because their feathers fan out to cover their bodies.

It’s interesting to realize that the bare spot on the belly (arrow points to v.apt) is a good beginning toward a brood patch for incubating eggs and brooding young.

Some birds are exceptions to this rule. Penguins’ feathers sprout uniformly across their bodies. You can’t blow on a penguin’s belly and see its skin.

I’ll bet the lack of pterylae explains why penguins don’t use their bellies to incubate their eggs. They use their bare feet!

(clip art from the Florida Center for Instructional Technology (FCIT) at University of South Florida. Click on the image to the see the FCIT clip art library.)

Kate, you are a genius; at least you know your stuff, thanks!

I have loved anatomy lessons and am disappointed to have them end. You have made it quite an interesting series. (I’m hoping for that July restart)!