This week I found a bumper crop of haws littering the sidewalks in Schenley Park.

Haws are the fruit of hawthorn trees: short trees with low branches, tangled twigs and long, thin, leafless thorns (1″-2″ long). The thorns are a great clue for identifying the tree. Haw+thorn.

Hawthorn fruits look like small apples or rose hips, all members of the rose family. They’re a favorite food of robins and cedar waxwings, and people sometimes preserve or ferment them into jam, jelly, snacks and beverages. The trees occur worldwide in the northern hemisphere so there are many recipes.

Hawthorn trees are really easy to identify as a genus (Crataegus) but difficult as a species because they hybridize and speciate so often. At one point botanists listed more than 1,100 species in North America but they’ve since clumped them down to about 100.

The Sibley Guide to Trees says hawthorn species are so similar that identifying them is best left to experts. However, armed with rudimentary knowledge and my Sibley guide, I’ll go out on a limb for these Schenley trees.

My guess is that they’re a variant of Downy Hawthorn (Crataegus mollis) because the haws are ripening in August and the ripe ones soon fall to the ground.

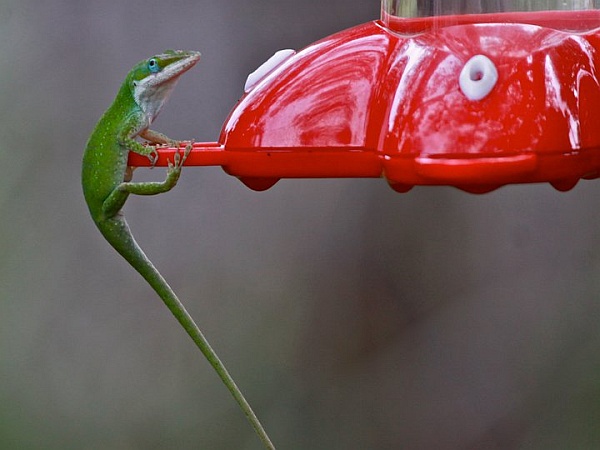

(photo by Kate St. John)