Eggs are familiar objects that miraculously become baby birds. The process is so amazing that I’m devoting two Tenth Page articles to it.

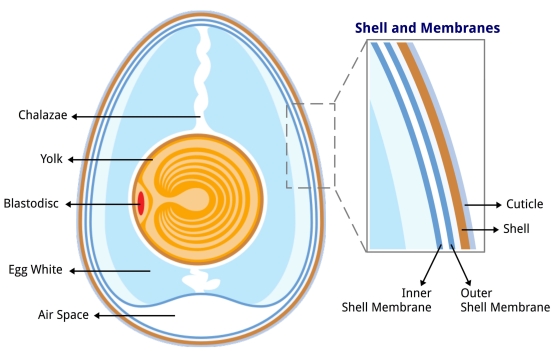

Shown above is the un-incubated egg we know so well. If fertilized before it’s laid, and then incubated, it becomes a bird. Each component plays a part.

- Blastodisc or germinal disc: Potential embryo. If fertilized and incubated this small circular spot on the yolk becomes a chick.

- Yolk: Food for the embryo. The female’s ovary deposits layers on the yolk to increase its size before ovulation. Yellow layers are laid on during the day, white ones at night, so the yolk has rings like a tree. It’s housed in a yolk sac which is why you have to “break” the yolk when cooking. The yolk is ovulated with the germinal disc attached (cradled by the yolk) so the food is next to the potential embryo even before fertilization. As the embryo develops, the yolk shrinks.

- Albumen = Egg White: Food, water, shock absorber, and insulation from sudden temperature changes. The albumen makes up 50% to 71% of the egg’s total weight. It’s laid on after fertilization while the yolk-with-germinal-disc rotates gently in the oviduct. As the embryo develops the albumen shrinks too.

- Chalazae: Because the yolk is rotating during albumen deposition, twists form in the albumen. Chalazae act like springs and stabilizers to keep the yolk and embryo in place inside the egg. They’re the white twisted bits in the egg white. (Totally amazing! Shock absorbers, insulation, springs and stabilizers!)

- Inner Shell Membrane: the first of two membranes that hold the embryo-yolk-albumen together

- Air Space: Between the inner and outer shell membranes the air space acts as a condenser for moisture exchange. This is where the baby bird takes its first breath before hatching.

- Outer Shell Membrane: The final packaging before the shell is laid on. It’s attached to the shell when you crack open an egg.

- Shell: The female’s uterus deposits calcium on the outer shell membrane to make the hard enclosure for the egg. The shell has microscopic pores to allow air exchange for the developing embryo.

- Cuticle: A thin layer on the shell that adds protection. The cuticle has caps on top of the pores that close when necessary to protect the embryo.

Eggs have the tools and potential to become baby birds. Click here to learn how the chick develops.

(illustration from Wikimedia Commons; click on the image to see the original. Today’s Tenth Page is inspired by page 420 of Ornithology by Frank B. Gill.)

Yes, but how many chicks have we now? I can only see two eggs in the most recent snapshot.

3 eggs still to hatch. One baby is hiding an egg with his body. A function of the camera angle.

Early this morning, the poor little second chick looked so exhausted after his hatching ordeal, and all the older one was doing was begging for food, of course!

Colleen, hatching is hard work! Just saw the second one joining in on lunch a while ago though. In peregrine nests, everyone gets as much to eat as they want. This even playing field started all the way back a month ago as Dorothy waited until all but the last egg were laid to begin incubating so that they’d all develop at about the same rate. This isn’t true for all raptors. Eagles for example will begin incubation immediately, and so the eggs hatch staggered as well. The first chick to hatch in an eagle’s nest can have quite an advantage by the time any siblings come along.

Now to keep an eye on the rest of those eggs and hope they’re all able to hatch soon! (just for hatching’s sake, not because I’d worry about the chicks being too far behind the first two)

There’s even a post on this blog about peregrine chicks and feeding if you want to read more. http://www.birdsoutsidemywindow.org/peregrine-faqs/question-are-the-chicks-getting-enough-to-eat/

Kate! How about where the calcium for the shell is derived from! It is scary to me…but just Another wonder of the bird!!!