A timely science lesson for New Year’s Eve.

p.s. Don’t try this with champagne!

p.p.s. Do you hear the bird singing at 20 seconds into the video? Sounds like a Common Blackbird (Turdus merula).

A timely science lesson for New Year’s Eve.

p.s. Don’t try this with champagne!

p.p.s. Do you hear the bird singing at 20 seconds into the video? Sounds like a Common Blackbird (Turdus merula).

30 December 2015

Freeze. Thaw. Freeze. Thaw. In this non-winter of 2015 we’ve had days and weeks of warmth punctuated by occasional frosts. Eventually the freeze-thaw cycle produces fermented fruit and that leads to drunken birds.

Fruit ferments outdoors when freezing temperatures break down the hard starches into sugars and then a thaw allows yeast to get into the softened fruit and begin the fermentation process.

The sweet, soft fruit is particularly tempting to birds. After a good frost the ornamental trees in my neighborhood, like the one above, are swamped with hungry starlings and robins. When they swallow a fermented berry it has a fizzy zing, but so what? It tastes good.

But some birds don’t know when to stop. They eat so much fermented fruit that they walk with a wobble and can’t fly straight. When they’re falling-down drunk, they end up in “detox” at a wildlife center until they sleep it off. Bohemian waxwings are famous for this.

Back in 2014 National Geographic reported on an incident in Whitehorse, Yukon when a bumper crop of fermented rowan (mountain ash) berries were the waxwings’ undoing. The birds were in such bad shape that they ended up in Meghan Larivee’s “drunk tank” at Environment Yukon.

It turns out climate change is increasing the likelihood of these episodes up north. National Geographic explains:

Larivee’s recent waxwing patients were admitted to her Yukon animal unit following several frosts and thaws due to warmer temperatures. … While fermentation is most pronounced in winter, “we also likely have longer autumns, which gives more time for berries to ferment, but still have early frost that allow sugars to be produced in berries early in the fall,” she said.

The waxwings were drunk on climate change.

Read more here in National Geographic.

(photo by Kate St. John)

I don’t usually write about bridges, but there was big excitement only 1,200 feet from my house yesterday when contractors blew up the Greenfield Bridge. As you can see from the photo above, it connected my neighborhood to Schenley Park (right of photo) over the Parkway East I-376. I haven’t been able to walk into this part of Schenley since the bridge closed on October 17.

Even if you don’t live in Pittsburgh, the implosion made national news so you probably saw videos on TV. Here are some photos of the event, a bit of the birds’ perspective, and links to my favorite implosion videos.

Above, a birds-eye view of the bridge on Christmas Eve. Below, the bridge is wrapped, charged, and waiting on Monday morning, December 28.

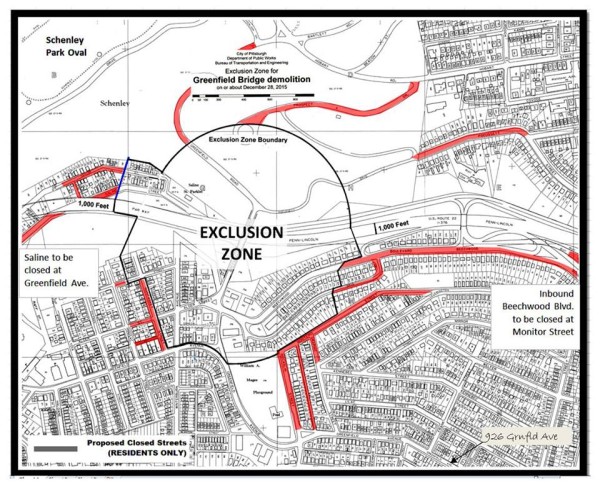

The implosion required a lot of warning, coordination, street blocking and police patrols. The map below shows the exclusion zone.

Folks could stay home if their house was inside the circle but they had to stay inside and away from windows. If you live that close to something this exciting, you either left home to watch nearby or you saw the best view of all on TV.

My house is outside the circle but I watched from one of the red roads closed to traffic. Those roads have good views but were open only to pedestrians to prevent gawkers’ cars from causing traffic and parking problems. It was fun watching with the neighbors. We were all in a party mood.

Starting an hour+ before the blast an infrared sensing helicopter circled overhead to make sure no one was outdoors within the exclusion zone. One guy snuck into the woods and had to be rousted out. We never saw him but he delayed the blast 20 minutes.

Back in October the neighborhood held a party and raffled off a chance to push the plunger and blow up the bridge. Sally Scheidlmeier, pictured below, won that honor. Here she is with the plunger (“Let’s Do It”) and the plunger’s victim in the distance, only minutes before the blast. She pushed the plunger …

… and then …

Here’s my favorite video of the blast from the Post-Gazette. Watch for the guy in the hard hat and orange-yellow vest who runs into the picture and down the road. That’s a man who loves his job!

Down in The Run (the neighborhood in the valley on the left side of the exclusion zone), Trinidad Regaspi took a video with her cellphone. Do you see that bird-like dot to the right of the telephone pole? It’s one of four wild turkeys that flew across the valley to escape the noise. They sure had a story for their friends last night!

… and then the bridge was gone.

It didn’t take long before the contractors were down on the Parkway picking up the pieces. Six pillars on the Schenley side didn’t fall during the blast but they came down shortly after I took this photo at noon. Alas, I missed it.

At road level there’s a lot of debris.

The contractors are out there picking up the pieces all day and all night (we can hear them). They have to work fast because they only have permission to keep the interstate closed for 5 days after the blast.

I-376 is slated to reopen on January 1 at 6:00am. The new bridge will take 18+ months to build.

Read more and see additional videos here at the Post-Gazette.

(photos from Pat Hassett, Geoff Campbell, Trinidad Regaspi and Kate St. John)

UPDATE DECEMBER 31, 2015: The cleanup finished ahead of schedule! The Parkway East opened INBOUND today at 2:00pm. OUTBOUND will reopen between 10:00pm and midnight because of another project down the road at the Birmingham Bridge.

This month I hiked the Wetlands Trail at Raccoon Creek State Park in Beaver County where I found many small trees chopped down next to Traverse Creek lake. Across the water, cut treetops and shrubs lay in a messy half-submerged brush pile against the opposite shore.

The stumps don’t show the straight-edge cut of human activity. If you look closely you see tooth marks. Big incisors were at work.

Beavers!

Beavers (Castor canadensis) are obviously here now, but that wasn’t always the case.

When Beaver County was named for the Beaver River in 1800, their namesake was already hard to find. The North American beaver population was 100 to 400 million before Europeans arrived to trap them but 300 years of over-hunting took its toll. According to the PA Game Commission, “the last few beavers known to naturally exist in Pennsylvania were killed in Elk, Cameron, and Centre counties between 1850 and 1865.”

Game laws and reintroduction programs have brought beavers back to 10% of their former population. Today there are 10 to 15 million beavers in North America.

In Pennsylvania one indication of the beavers’ success is the number of complaints they generate, mostly about flooding including plugged culverts and flooded roads. A lot of complaints often means there are a lot of beavers.

Where were the most complaints in 2008 in southwestern Pennsylvania?

In Beaver County.

(photos by Kate St. John)

Back in November I found these round hairy growths on the backs of many oak leaves at Hillman State Park in Washington County, PA.

From above they look furry but up close I can see that they’re fibrous.

No doubt these are galls, structures grown by the tree itself in response to chemicals deposited by a tiny insect that laid eggs on the underside of the leaf. The insects are usually gall wasps (Cynipidae) whose larvae are protected by the gall.

There are 750 species of Cynipidae in North America, best identified by the characteristics of the gall and the plant it’s growing on. What does the gall look like? What species is it growing on? Where is the plant located (geographically)? What part of the plant is the gall growing on? If on a leaf, is it on the upper or under side? Is it on a twig? A bud? Etc. etc.

Extensive searches of bugguide.net produced similar photos but no final identification. The closest was this one: A gall wasp (Cynipidae) in the genus Acraspis, photographed in Guelph, Ontario.

So I’m back where I started. I know the name of the wasp (as far as I care to know) but what is the name of the gall?

(photos by Kate St. John)

When my camera couldn’t capture this horizontally, I turned it sideways to photograph the trees.

I like them this way better than in the “normal” orientation.

Put your left ear on your left shoulder to see what I mean.

p.s. I took this photo four years ago but didn’t label it. Based on their bark I think these are sugar maples … but their branches don’t look right.

(photo by Kate St. John)

Merry Christmas, everyone!

This beautiful Christmas Star Dahlia from Paul Staniszewski reminds me that there are gorgeous flowers and light displays at Phipps Conservatory’s annual Winter Flower Show and Light Garden, open tomorrow through Sunday January 10.

Do they have this dahlia? I’ll have to go and see …

(photo by Paul Staniszewski)

This year’s El Niño has made it too warm for snow on Christmas. Way too warm!

Today’s forecast high of 65o F is almost 30 degrees above normal.

In Pittsburgh it’s going to feel like Christmas in Florida without the palm trees. Florida will be hotter than normal, too.

No snow, no skiing east of the Mississippi.

We’ll just have to dream …

(photo by Steve Gosser)

Here’s a bird whose migration takes him through four hemispheres and two oceans.

Thanks to a tiny tracking device placed on 10 male red-necked phalaropes on Fetlar Island, Scotland in 2012, the RSPB learned that these North Atlantic birds fly west and south to spend the winter in the Pacific Ocean off the coast of Ecuador and Peru.

Their amazing route starts in the Northern and Eastern hemispheres and ends in the Southern and Western hemispheres. They spend the winter at sea in the plankton-rich Humboldt Current.

Red-necked phalaropes (Phalaropus lobatus) are small birds with a circumpolar distribution. The European group is thought to winter at the Arabian Sea but the Fetlar Island birds follow the same southward migration route as those from eastern North America, so it’s likely the Scottish phalaropes are related to that population.

Read more and see a video about their long migration here at BBC News.

And if you want to see a red-necked phalarope, your best chance is in the Bay of Fundy during spring or fall migration. Two million have been counted there in the months of May and August(*).

(photo of male red-necked phalarope in San Jose, CA in the month of July from Wikimedia Commons. Click on the image to see the original.)

How fast do peregrines dive?

Watch this National Geographic video of Ken Franklin — pilot, falconer, sky diver — as he clocks his peregrine falcon, Frightful, diving for the lure.

Talk about fast!

(YouTube video from the National Geographic Channel, December 2007)