What’s the difference between a moth and a butterfly?

The first and best clue is the difference in their antennae: Moths have a variety of antennae shapes, one of which is very feathery, but they never have knobs. Butterfly antennae always have knobs on the end and are often smooth.

The feathery antennae above are on an Agreeable Tiger Moth (Spilosoma congrua) photographed by Chuck Tague.

The knobbed antennae, below, are on a Pearl Cresent butterfly (Phyciodes tharos).

There are additional clues:

Second clue: Is it flying? Moths fly at night(*), butterflies fly during the day.

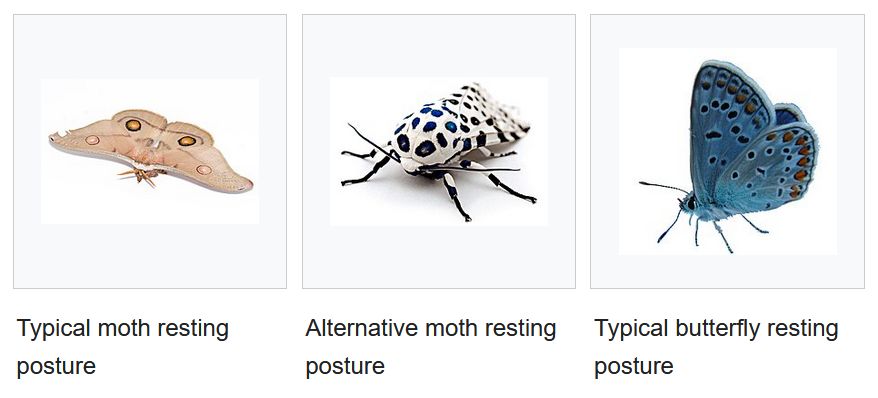

Third clue: How does it hold its wings when resting? Moths open their wings flat (as above) or fold them tightly flat over their backs. Butterflies hold their wings upright, clapped shut above their bodies(*).

(*) Of course there are exceptions. Read about them in Wikipedia’s Comparison of Moths and Butterflies.

(photo of Agreeable Tiger Moth by Chuck Tague. photo of Pearl Crescent Butterfly by Kate St. John)