24 August 2011:

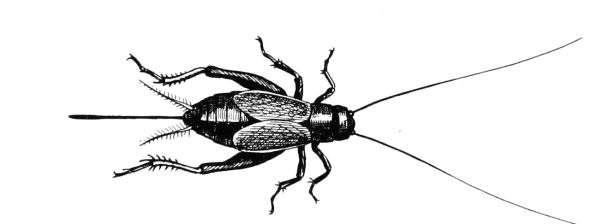

Most moths are nocturnal but Dianne Machesney found this Chickweed Geometer Moth during the day at Hillman State Park.

How can you tell it’s a moth?

First clue: Is it flying? Moths fly at night(*), butterflies fly during the day.

Second clue: How does it hold its wings when resting? Moths open their wings flat (as above) or fold them tightly flat over their backs. Butterflies hold their wings upright, clapped shut above their bodies(**). Click here to see an illustration of these postures.

Third and Best Clue: Look at its antennae. Moths have fuzzy antennae with many tiny branches. Butterflies have smooth antennae with little knobs at the end.

Of course there are exceptions. The Chickweed Geometer moth flies during the day (* erf!). However, the males have very fuzzy antennae. You can tell this moth is a boy.

For more information on the differences between moths and butterflies, see a summary at Live Science or this detailed discussion at Wikipedia.

(photo by Dianne Machesney)

(**) p.s. Skippers are butterflies but their resting posture is halfway between that of a typical moth or butterfly.

A bird’s chin is exactly where you’d expect it to be — just under its beak — but of course birds’ chins don’t stick out like ours do.

A bird’s chin is exactly where you’d expect it to be — just under its beak — but of course birds’ chins don’t stick out like ours do.