I usually don’t chase rare birds because I am so disappointed when I drive a long way and don’t find what I came for, so in December 2005 when Andy Markel reported a juvenile prairie falcon in the open fields of Cumberland County north of Shippensburg I did not go see it.

Over the next few weeks Andy and others found and photographed the prairie falcon again and again. It was so far out of range that many wondered if it was a falconer’s bird but no one could prove it. The bird stayed through the winter and then was gone.

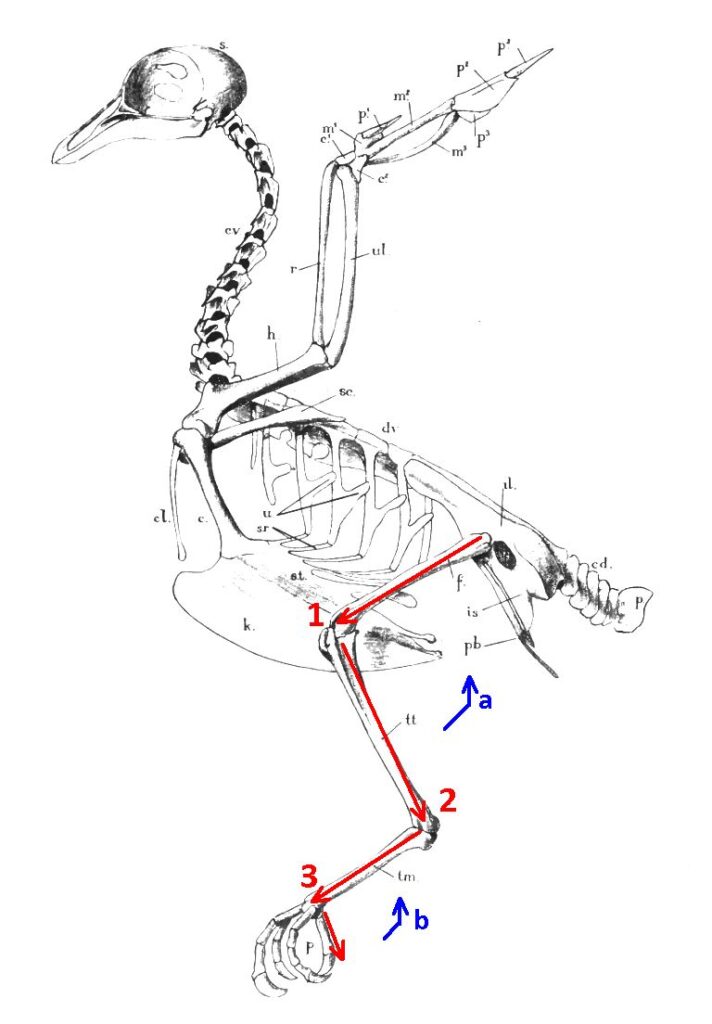

Prairie falcons (Falco mexicanus) are western birds of cliffs and open country. They’re the same size and shape as peregrines except that they’re pale brown and white with dark axillaries (armpits) and pale heads. They range from California to Colorado, from southern Canada to Mexico. They never come to Pennsylvania.

But this one does. Every winter the prairie falcon returns to the same place on Mud Level Road. Now, of course, it’s an adult. In February 2008 it was found so easily that many birders made the trek to see it and even discovered that it roosts at a quarry a mile away from its daytime haunts. (Prairie falcons like cliffs just as much as peregrines do.)

Still I did not go to see it. The 3 hour drive from Pittsburgh was too long for the disappointment I was bound to encounter.

But this year the falcon came back early — November 20 — and I was going to be in Hummelstown for Thanksgiving, only an hour away. Saturday morning, November 27, was my only chance to chase it.

Long before dawn I drove to Cumberland County and found two other birders already at the intersection of Mud Level and Duncan Roads. Neither had found the bird but with more eyes on the sky we stood a better chance.

Soon we saw a falcon hazing the pigeons northwest of Mud Level but even through a scope the bird was impossible to identify. Jonathan Heller and I drove to Brinton Road for a better look but could not relocate the bird. Mike Epler stayed behind, then drove the circle. No luck.

Back and forth we searched. Jonathan and I tracked a falcon that didn’t look quite right but it was our best candidate. We finally caught up to it just as it landed in a tree on Brinton Road. We screeched to a halt, jumped out of our cars and identified … a merlin.

At any other time and place a merlin is a good find but we were disappointed. This was made worse when Mike drove up and told us he had just seen the prairie falcon at Mud Level and Duncan. He had watched it retrieve a mourning dove dropped by a harrier, then perch and eat the prey close enough for a great look.

Aaarrrgg! We went back to our starting point but the bird was gone.

Jonathan was preparing to leave so I took a slow drive down Mud Level Road contemplating the ephemeral nature of rare birds. I told myself that on this trip I’d heard horned larks and seen a merlin, kestrels, northern harriers and red-tailed hawks — and that should be enough. Sigh.

No point in looking anymore. Sigh.

I drove away slowly down Duncan Road.

A pale brown hawk, very pale, on a hay bale, caught my eye. It had its back to me and was eating. Oh my! I pulled off the road and parked near the hay bale. I rolled down the passenger window and had an excellent view of the prairie falcon as it ate a bird.

The falcon looked around, his cere and eyerings yellow, his legs brighter yellow, his head quite pale.

Though I stayed in my car I made him nervous. He bobbed his head, then picked up his prey and flew to another hay bale. In flight I saw his dark axillaries. Again he was nervous, flew down to the ground, then eventually northwest across Mud Level Road. Good bird!

I’ve now seen every falcon that normally occurs in North America except the aplomado. (It occurs from Mexico to South America, rarely in the southwestern U.S.)

Needless to say the bird in this photo is not the one at Mud Level but it captures his look and posture. For an even better look, click here for a flight photo and you’ll see the dark feathers under the wing.

(photo of a prairie falcon by Matt MacGillivray via Wikimedia Commons. Click on the photo to see the original)