29 August 2012

Smooth clouds like this are my favorite because they look like lozenges or flying saucers. Sometimes they’re in compound shapes like this “hat” on Mt. Hood.

Lenticular clouds are most common near mountains because the wind hits the mountain, creates an updraft and becomes a large standing wave. When moisture condenses at the top of the wave, a stationary lenticular cloud forms there. The long lozenge shapes are usually perpendicular to the wind. They sure don’t look that way!

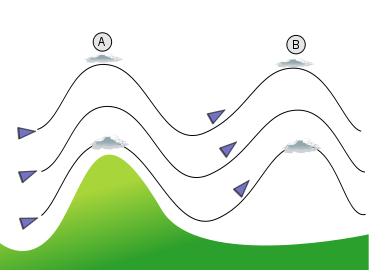

When the wind hits the mountain the waves look like this.

Notice the stationary clouds at crests A and B. The wind follows the shape of the mountain — twice! The updraft on the windward side of the mountain is provides uplift for glider pilots but the downdrafts can be deadly. There’s a lot of turbulence in those standing waves. Powered aircraft avoid them.

Pittsburgh rarely has lenticular clouds, though a front creates one occasionally.

For really cool clouds you have to visit the mountains.

(photo of cloud by Yapin Wu via Wikimedia Commons. Diagram of wave lift by Dake on Wikimedia Commons. Click the captions to see the originals.)

Thank you for this beautiful picture and for your interesting website. This cloud reminds me of the winter waterspouts I saw once in Maine over an inlet of Casco Bay. It was during a very cold winter a few years ago, while I was out running at 5 a.m. The temperature was below zero and I understand these phenomena are quite rare and there are only a handful of photos of them. While I was running around Back Cove admiring the gorgous white plumes that touched the water and went up into the sky, I also noticed a snowy owl nearby, following me as I ran by, with its head swiveling around. Can owls really turn their heads completely around more than 360 degrees?

Snowy owls can turn their heads 270 degrees – so far that it looks like full circle.

Very rarely Pittsburgh sees lenticulars forming atop and leeward of cumulus buildups, which are the closest things we have to big mountains in that respect. This is a very exciting development for pilots, particularly glider pilots, who can use the upward-moving currents to fly very high and very far. (This is noted on the Wikipedia page.)

Our soaring club (http://www.pittsburghsoaringclub.com) has a legend of a day in the ’90s when this condition was taking place—one club member was able to contact the wave, fly above the cumulus layer, and climb well over 10,000 feet. As for myself, I have climbed to 9,000 feet in wave over the Appalachian ridges, but wave in those places doesn’t reliably produce lenticulars.

I don’t think I’ve ever seen a cloud like that. Amazing!

It makes me think of a parked UFO.

Hello, I very much enjoyed your picture of the mountain wearing a hat. I am currently engaged in a long-running debate with my kids about whether mountains wear hats. Please confirm that mountains wear all kinds of hats by posting pictures of a mountain wearing each of the following kinds of hats: a baseball cap; a pirate hat; a top hat; old timey old lady hat; a witch’s hat; a cowboy hat; and a train conductor’s hat. Thank you in advance.