5 September 2012

When I wrote about lenticular clouds last week Tom Stepleton of the Pittsburgh Soaring Club commented on how useful they are for glider pilots — a sure sign of an updraft that will take a glider high and far.

He also mentioned another orographic cloud that’s more common above Pennsylvania’s mountains: the wave.

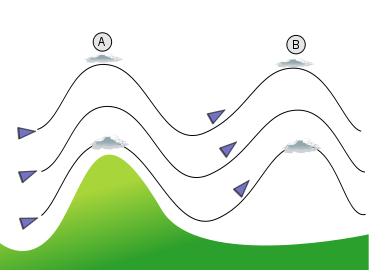

This photo, taken by a glider pilot, shows two waves with a window over Bald Eagle Valley in north central Pennsylvania. The clouds are formed by the same wind pattern that creates lenticular clouds but instead of creating a lozenge-shape the long ridge produces a wave.

The best conditions often occur in the fall when a cold front brings northwest winds that hit the mountains at a 90 degree angle.

Pictured here the wind hits the Allegheny Front (on the left) and rises up to create the first wave. The air drops and creates a window over the valley, then rises again to create the second wave.

The pilot was flying north but I’m sure he saw hawks heading south using the same updraft to make their journey easy. (This photo was taken in autumn; the trees are changing color.)

It would have been a good day to be at the Allegheny Front Hawk Watch … as long as that cloud stayed well above the ground.

(photo by Dhaluza on Wikimedia Commons. Click on the photo to see the original and read more about it.)