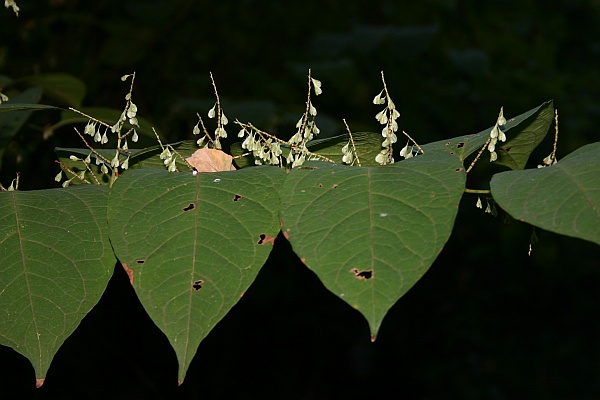

What are these spiky flowers Charlie Hickey found peeking out of a lake near his home?

Charlie identified them as Eurasian Water-milfoil (Myriophyllum spicatum) an invasive aquatic weed with soft, feathery, submerged leaves that form thick mats in North American lakes. Click on the photo and scroll down to read his description of it.

When I looked further I was amazed to learn that…

- Eurasian Water-milfoil can propagate from a small piece of stem so a little bit caught in the boat propeller in one lake can be carried to another lake and spawn a new invasion. I saw signs in Maine warning people to clean their boats after they take them out of the water.

- North America has its own native water-milfoil called Northern Water-milfoil (Myriophyllum sibiricum). The two species can be identified by their leaves but they hybridize and the hybrid inherits characteristics of both. Very hard to identify.

- The invader is hard to get rid of. Many techniques have been tried including imported biological controls using a moth, a weevil and a fish. The fish didn’t work out so well. It prefers to eat native plants so it denuded the lakes and left the Eurasian water-milfoil for last.

- In the Adirondacks and New England divers remove it by hand every year. This technique is so successful that according to Wikipedia: “After only three years of hand harvesting in Saranac Lake the program was able to reduce the amount harvested from over 18 tons to just 800 pounds per year.”

How did water-milfoil get its name? My guess is that “milfoil” is a contraction of the French “mille feuille” which means “thousands of leaves.”

When it overruns a lake it looks like an invasion of a thousand — no, a million — leaves.

(photo by Charlie Hickey. Click on the image to see the original)