Lunch hour in Downtown Pittsburgh was extra exciting yesterday when one of the three peregrine nestlings made his first flight. Fledgling #1 landed safely on BNY Mellon’s plaza at Fifth and Grant and was rescued promptly by PGC Officer Kramer who placed him high on a nearby building to start over.

Michael Leonard, an Aviary volunteer and Pittsburgh Falconut, was passing by the area and helped guard the bird until the PA Game Commission arrived. Then he snapped this rescue photo. Great job, everyone!

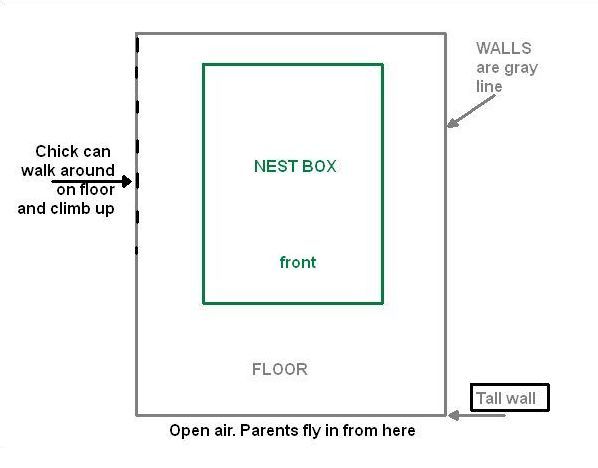

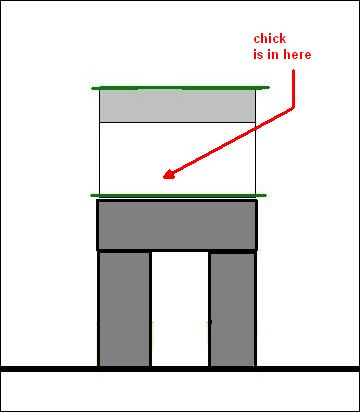

Fledgling#1 is just fine so he’s ready to make his second flight from a much higher location than his inaccessible nest. WCO Kramer put him on the “rescue porch” where he immediately and actively(!) checked out his surroundings. He was not banded (no bands available at time of rescue).

His June 11 flight was two days earlier than I expected but weeks of preparation paid off.

Knowing that Fifth and Grant was likely to be Ground Zero for fledglings, I circulated this flyer with the PGC phone number to nearby businesses and security guards. Perhaps someone used the flyer to make the call.

I also knew that rescued fledglings would need a higher zone than the 7th floor nest for their second take-off so I proposed a location, Art McMorris approved it, and Larry Walsh cleared the way. Thanks to John Conley who handles on-the-ground details and to The Business Most Affected By This (whom I won’t reveal for privacy of the porch & fledgling.) Many thanks to all!

Meanwhile two youngsters were still waiting for take off yesterday afternoon. The brown one looks like he might fly today. The other is younger and will wait a while. But who knows how long? I’m afraid to predict at this point.

Downtown Fledge Watch starts tomorrow where Fledgling#1 landed. Chances are there will be some excitement this weekend. Click the link for details.

C’mon down!

p.s. Check Matthew Digiacomo’s Flickr page for recent photos from the nest.

(photo credits: PGC rescue by Michael Leonard, Fledgling#1 on the “rescue porch” by Kate St. John, two nestlings by Matthew Digiacomo)