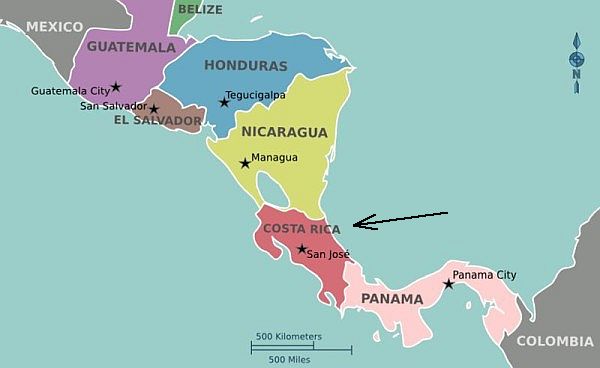

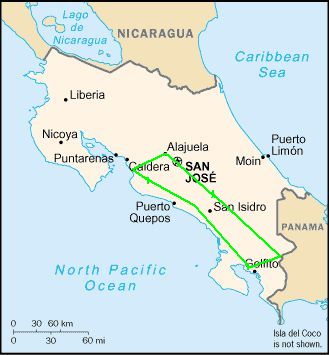

31 January 2017, On a birding trip in Costa Rica:

This beautiful bird is a male red-legged honeycreeper (Cyanerpes cyaneus) in breeding plumage in Costa Rica. He’s not the same subspecies as those found in Espírito Santo (ES), Brazil. (Alas, the beautiful video filmed at that location was deleted by the user.)

In southeastern Brazil the red-legged honeycreepers are members of the subspecies holti. Their “type specimen,” the bird that defines them, is in Pittsburgh at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History.

Back in 1940 when E. G. and M. L. Holt collected this bird in Espírito Santo, he wasn’t considered a separate subspecies. Then in 1977, Kenneth Parkes determined that he is indeed unique and named him Cyanerpes cyaneus holti. Field guides for southeastern Brazil refer back to this exact specimen at Carnegie Museum, placed here on his page in the Handbook of the Birds of the World.

Red-legged honeycreepers are common in Costa Rica, too, (subspecies carneipes) so I was looking forward to seeing this stunning blue bird while I’m here. However, I’d read on the same page (above) in the Handbook of the Birds of the World that Costa Rican males molt from blue to green right after the breeding season:

“In Costa Rica, male acquires eclipse plumage mostly between about Jul and Oct, and for the last few months of year almost all adult males are in eclipse; males in some stage of greenish “transition” plumage present in every month except Mar–May, when breeding.”

Oh no! Not always blue? What if they are all green like this?

Fortunately the males are very blue right now. Whew!

(video by Fabricio Vasconcelos Costa on YouTube. Type specimen photo by Kate St. John)

Day 5: Esquinas Rainforest Reserve