When I wrote about skunks last Friday, I said that “skunks carry rabies” but revised the text when Nathalie Picard pointed out that “carry” is misleading. Today I’ll explore the subject of rabies, who is at risk, and why the word carry is used for this disease.

Rabies is a virus that causes inflammation of the brain and death in mammals. Its pathway to humans is by a bite or scratch from an infected animal. When the virus first enters a human there are typically no symptoms for one to three months, though that period can range from 4 days to several years. During the asymptomatic period the victim feels fine.

When symptoms finally appear rabies has reached the fatal stage and the victim will die in 2-10 days. The only cure is a preventive vaccine (PEP) which must be administered within a few days of the original bite, long before symptoms appear. (Read more here.)

Dogs are the main hosts and transmitters of rabies. Worldwide more than 17,000 humans die of rabies every year, 99% of them from dog bites. 95% of the deaths occur in Asia and Africa where dog rabies is poorly controlled and the post-exposure vaccine is unavailable. More than a third of the deaths occur in India. (quoted from World Health Organization)

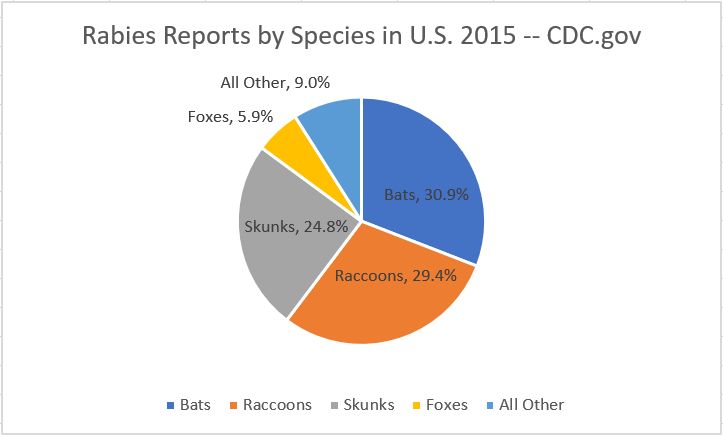

In the U.S. 92% of rabies comes from wildlife — bats, raccoons, skunks and foxes — called “rabies vector species” because they are at high risk for catching the disease. Since post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) is readily available here, only 2 or 3 people die of rabies per year.

Bats are the main cause of rabies death in the U.S. because people either do not realize they were bitten by a bat while sleeping/drunk/disabled or they do not seek treatment. Those who handle wildlife are vaccinated against rabies in advance.

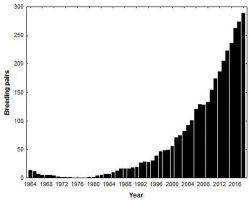

Here’s a graph of the CDC’s rabies statistics by species in the U.S. in 2015. All mammals can catch rabies. The low percentage species are lumped in the “All Other” category.

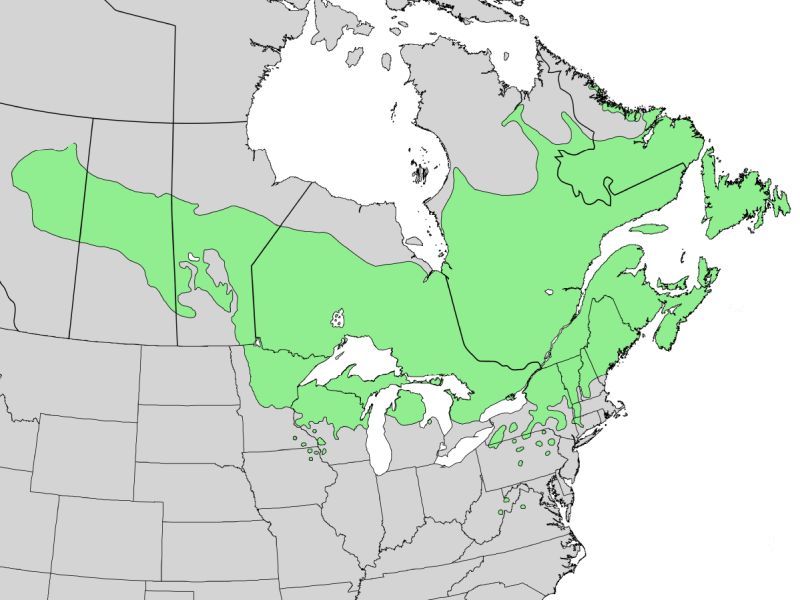

Aside from bats, raccoons are the main rabies vector in the eastern U.S. while skunks are the main vector elsewhere. Foxes are also a vector in Arizona, New Mexico and Alaska. (See CDC map here)

And finally … Why is the word “carry” used about rabies?

Wikipedia defines a disease carrier as a person or organism who’s infected by a disease but displays no symptoms. Since rabies has no symptoms at first, those with early stage rabies can be described as carrying it. High risk species are “vectors” not carriers. They don’t carry rabies until they catch it.

The bottom line is this: Avoid approaching wildlife, especially rabies vector species. Most of them are fine but you never know. If you are bitten or scratched, don’t wait to visit the doctor.

(photos from Wikimedia Commons; click on the images to see the original. In the composite photo at top: raccoon by D. Gordon E. Robertson and skunk by K. Theule/ USFWS)