Some birds are canaries in the coal mine, telling us that something’s gone wrong long before we notice it. Harlequin ducks (Histrionicus histrionicus) are performing that service in Alaska.

A 2017 study by the Biodiversity Research Institute looked for mercury in Alaska’s coastal waters by testing blood samples and molted feathers from harlequin ducks at Kodiak and Unalaska Islands. Blood samples were used because they indicate recently consumed mercury. Molted feathers show mercury when the feathers were formed a year before.

The study found mercury in harlequins from both locations but those at Unalaska, midway in the Aleutian chain, had eight times more than those at Kodiak, nestled in the Gulf of Alaska. The study then tested the ducks’ main food at Unalaska — blue mussels — and found it there, too.

This is important news for Aleutian residents because they eat lots of seafood. It also matters to the rest of us since Unalaska’s main port, Dutch Harbor, is the largest fisheries port in the U.S. by volume caught.

Mercury apparently increases westward in the Aleutian chain. A 2014 study found mercury in fish above the human consumption limit at the western island of Agattu.

Where is the mercury coming from? In the continental U.S. airborne mercury comes from coal-fired power plants and is regulated and reduced by the EPA. It can also come from active volcanoes, obviously out of our control.

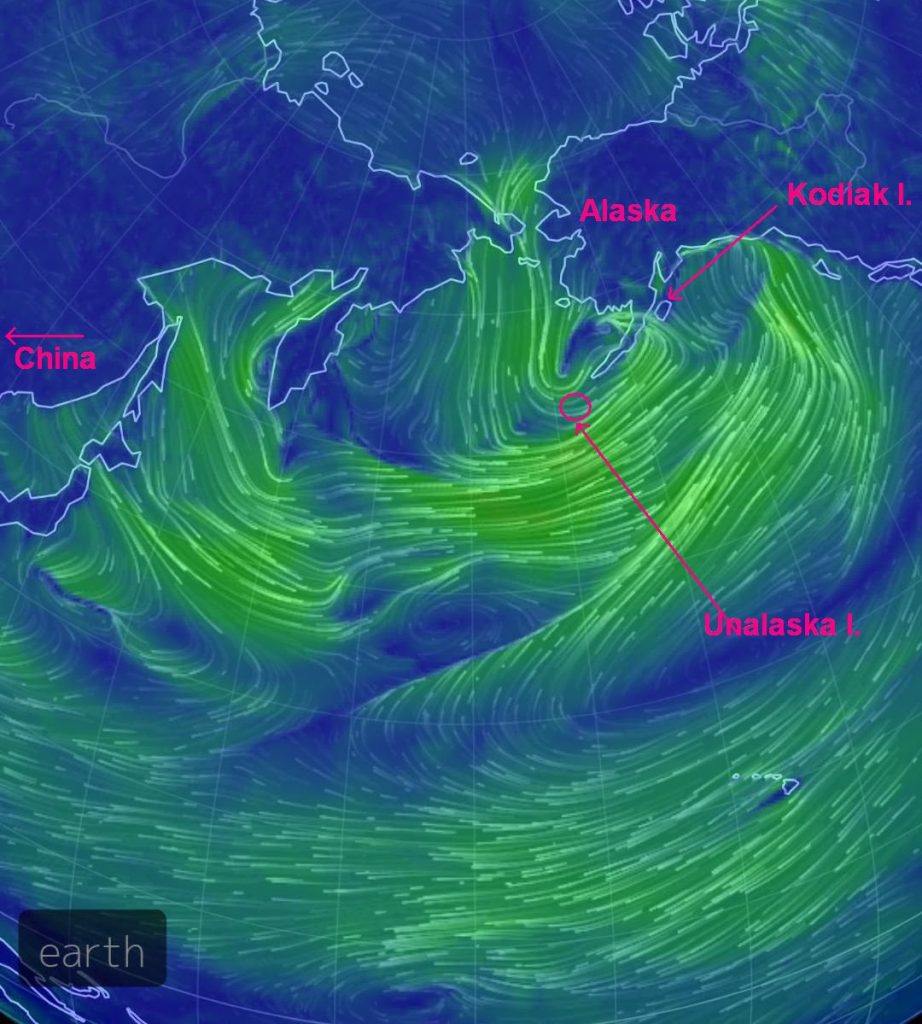

At this point scientists don’t know where the mercury is coming from, but China’s coal-fired industries are a good bet. The prevailing wind in the Aleutian Islands originates in Asia more than six months of the year.

Unfortunately Alaskans can’t prevent mercury pollution that reaches them from Asia. Meanwhile the harlequins warn of danger.

(photo of harlequin duck from Wikimedia Commons, screenshot of global winds from earth visualization website; click on the caption links to see the originals)

My dad was in Dutch Harbor while in the Navy during WWII. Interesting.

Dutch Harbor was probably fine back then for mercury.