30 July 2019

How do birds stay cool in hot climates, especially when there’s no shade?

A 2018 Australian study in the journal Nature found that some birds can reflect the hottest part of sunlight, the near infrared (NIR) spectrum.

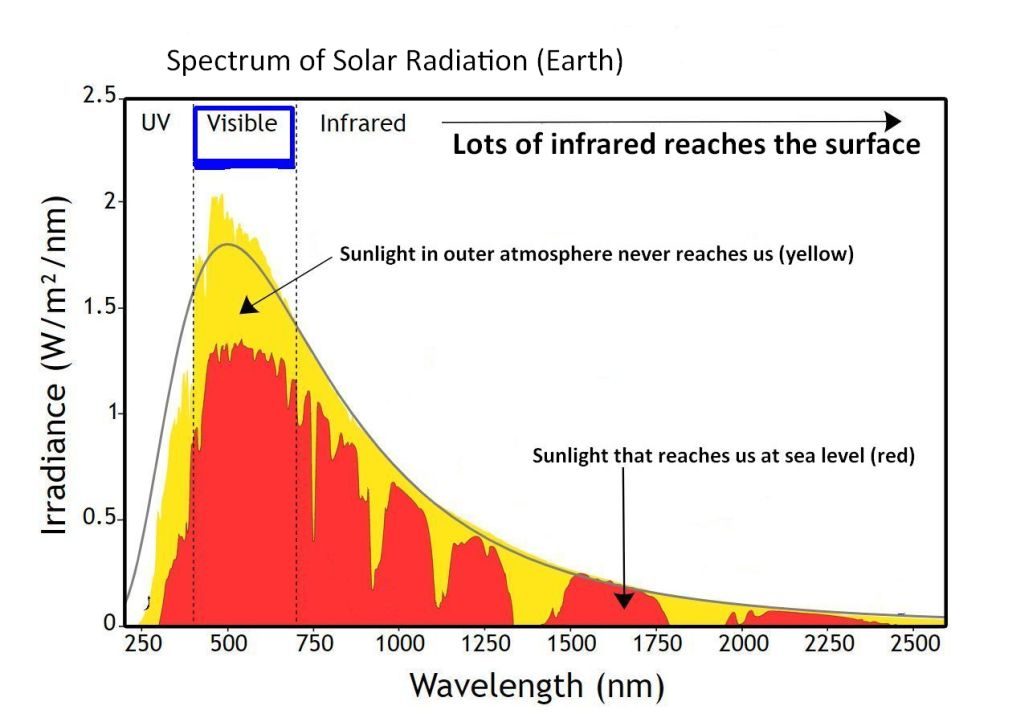

Near infrared is long-wavelength light beyond the red end of the visible spectrum. Though we can’t see this wavelength we can feel its heat. In fact more than half the sunlight that reaches Earth is in the infrared spectrum, as shown in the graph below.

Australia is a good place to study cooling techniques in birds because 70% of the continent is hot, dry and very sunny. The Australian study examined museum specimens of 90 species, classifying them by habitat and testing them for their NIR reflectant properties. Two species stood out.

The nankeen kestrel (Falco cenchroides), named for his yellow color (above), reflects near infrared light from the crown of his head. The azure kingfisher (Ceyx azurea) stays cool by reflecting NIR from his chest. Their feathers can reflect NIR because they have rounder barbs and denser barbules.

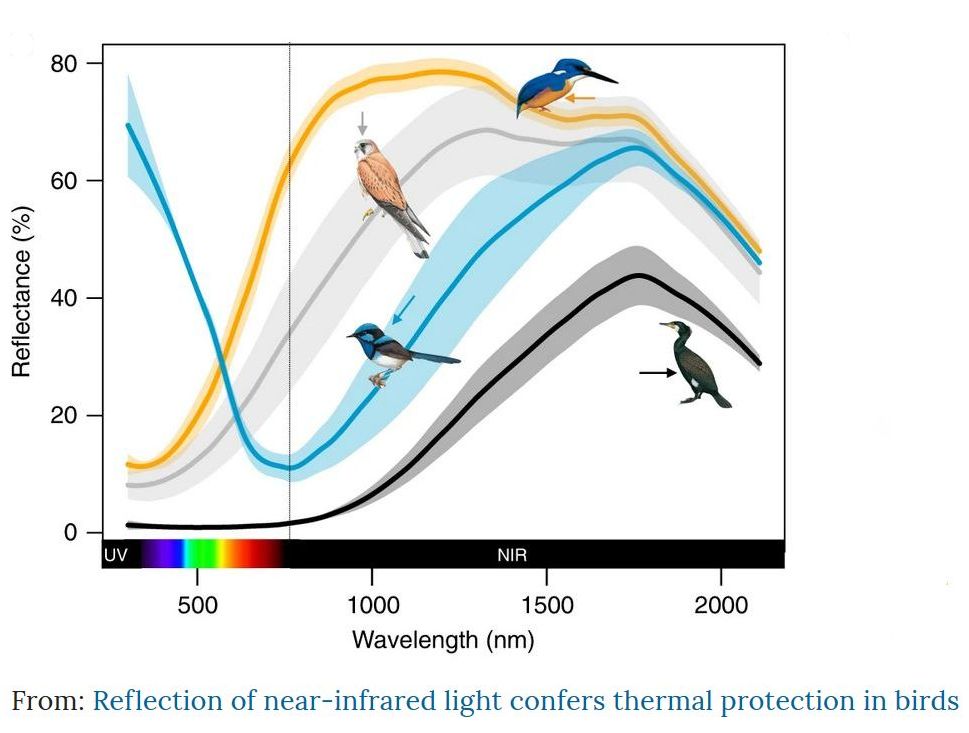

Here’s a graph from the study that compares them with two other species.

The nankeen kestrel and azure kingfisher are at the top of the NIR reflective scale but low reflectors of visible and UV light. The reverse is true of the blueish bird, a male superb fairywren (Malurus cyaneus). He’s great at reflecting UV and visible light, probably because he lives where it’s moist and shady. The great cormorant (Phalacrocorax carbo) doesn’t reflect much light at all.

Interestingly, near infrared reflectivity is more prevalent in small birds because they benefit more for their size. You can’t tell it from the photo but the azure kingfisher is only as big as a sparrow.

Too hot? Reflect near infrared light to stay cool.

(image credits: nankeen kestrel, sunlight graph and azure kingfisher from Wikimedia Commons. Graph from “Reflection of near-infrared light confers thermal protection in birds” at Nature.com, Creative Commons license. Click on the captions to see the originals)