5 September 2019

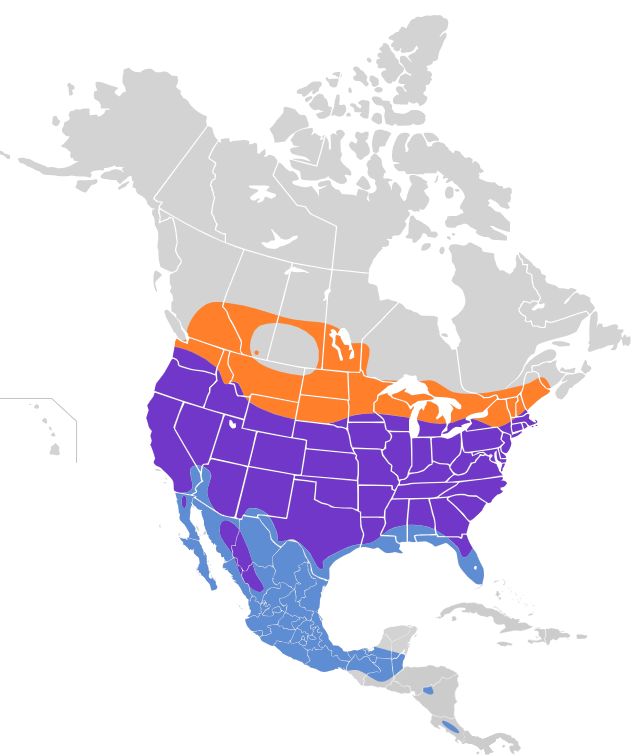

Songbird migration is underway across the continent but we can’t see it happening outdoors because the birds travel at night. However, we can watch them online.

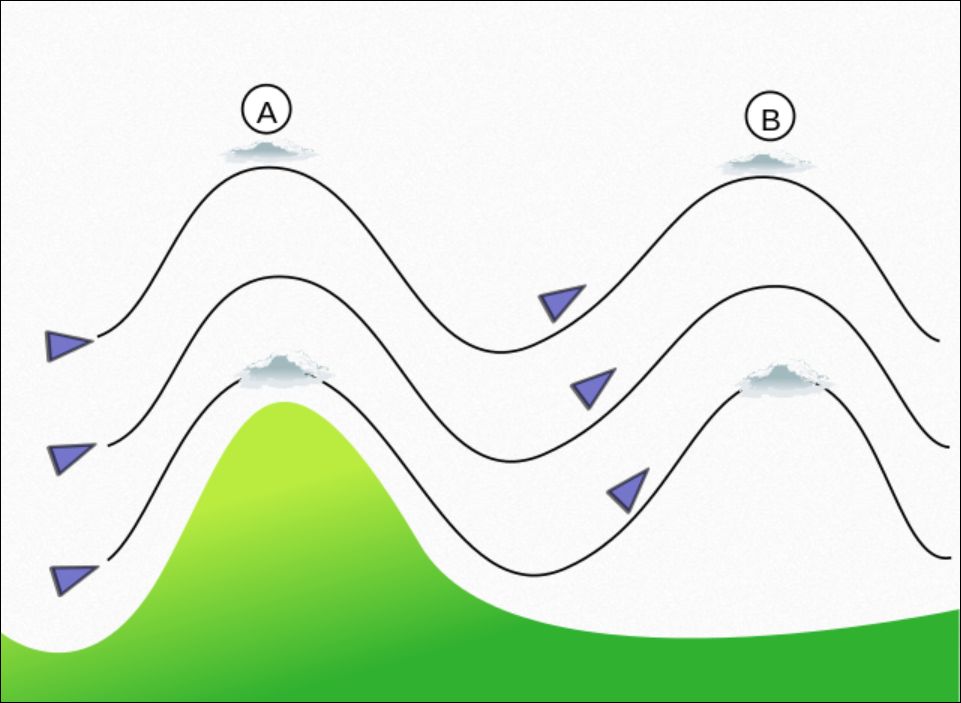

Radar can see birds in flight so Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s BirdCast uses national radar data to plot where, when and what direction the birds are moving. Click the BirdCast link to see the most recent video. Watch sunset (red bar) sweep across the continent and the birds start to move, then sunrise (yellow bar) sweep across and migration stops for the day. The date above the map is a pulldown menu for selecting prior nights.

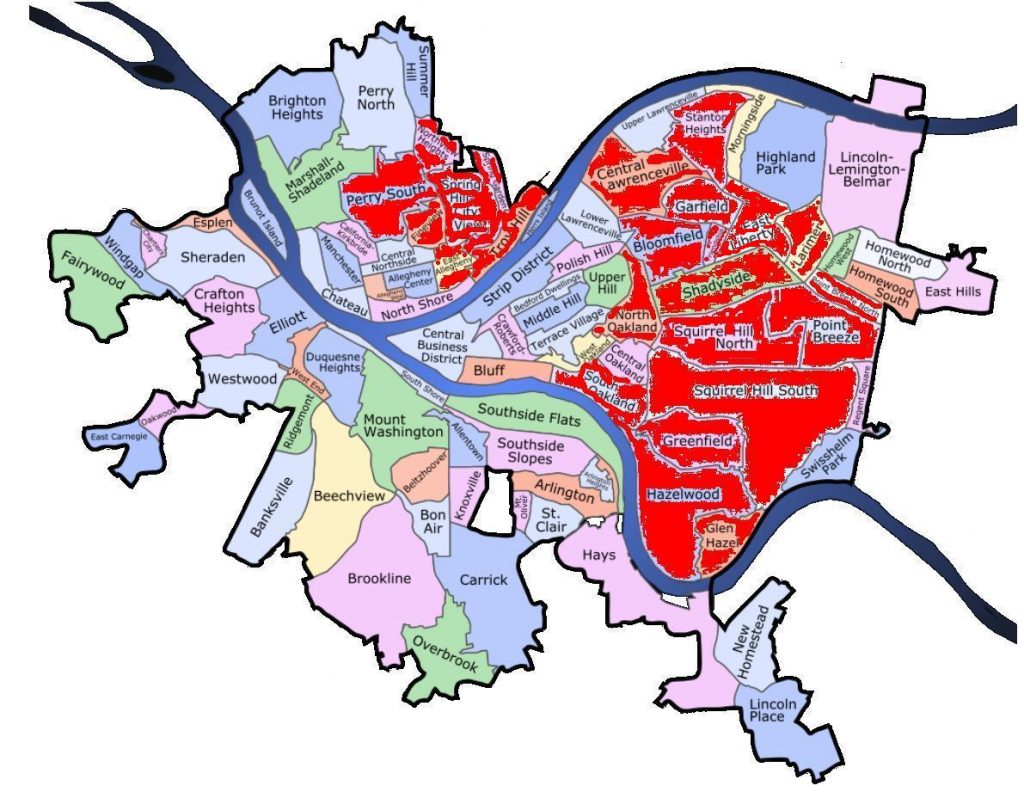

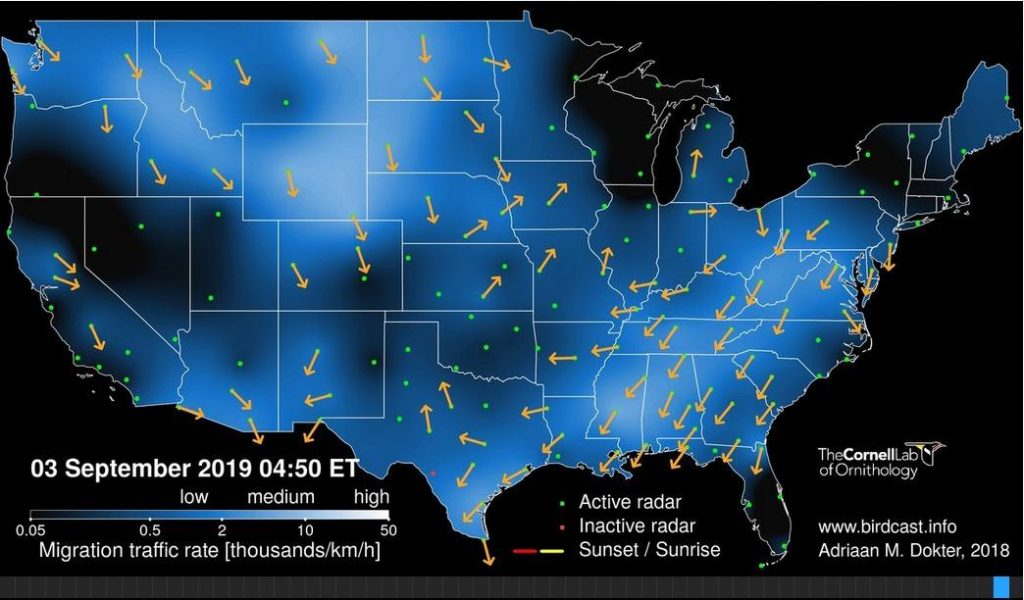

The BirdCast screenshot above was taken on Tuesday 3 September on a night when many birds left Pittsburgh on their way to the Gulf coast. At 4:50am you can see them lighting up the BirdCast map from southwestern Pennsylvania to Mississippi.

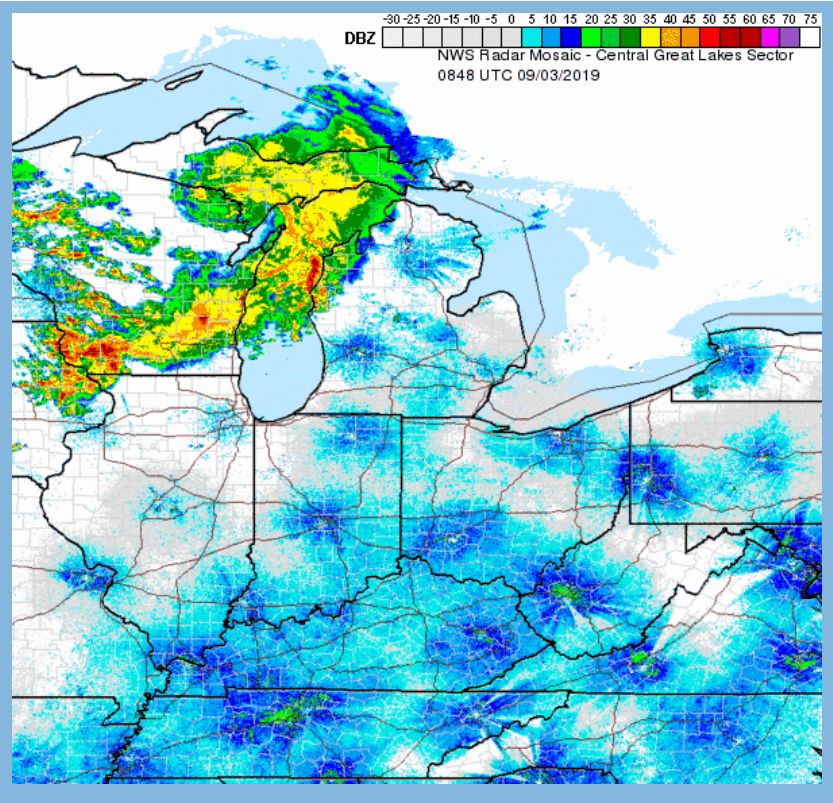

Before BirdCast existed, I watched weather radar for a snapshot of current bird activity. BirdCast filters the weather map so you see only the birds. The Weather Service does not so you’ll want to check out this vintage article — Watch Migration On Radar — for a quick tutorial on how to read the map.

The screenshot below was taken from Great Lakes weather radar on the same date and time as the BirdCast snapshot at top. Notice the differences!

Wisconsin and Lake Michigan are brightly colored on the weather map because of heavy rain. That same area is a dark spot on BirdCast because birds don’t migrate in a storm. BirdCast also shows no birds moving in Florida; Hurricane Dorian was there.

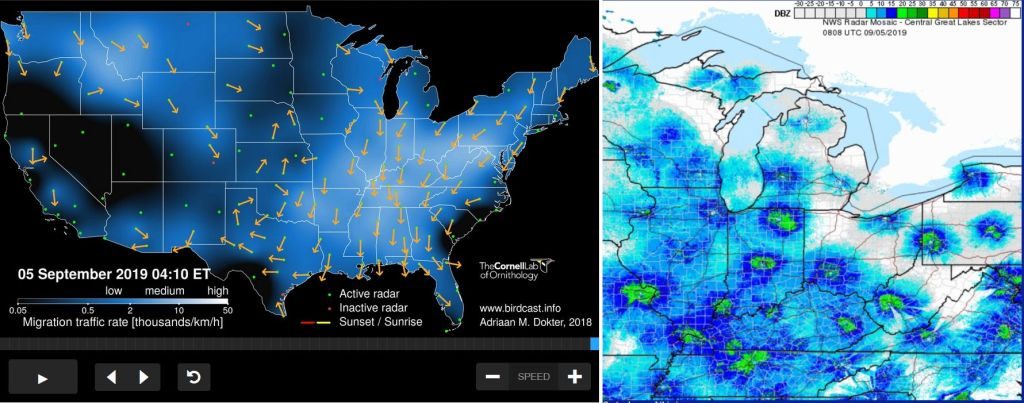

Last night, Sep 4-5, the wind was from the north and skies were clear west of the Appalachians. BirdCast and weather radar both show birds on the move from Pennsylvania and Illinois to the Tennessee and Mississippi Valleys.

It’s a good day to go birding.

(screenshot maps from BirdCast and the National Weather Service Great Lakes)