Though peregrines have spent the winter in Williamsport, PA for more than a decade, none nested there until a pair claimed the Market Street Bridge in 2013. This year’s nest produced one chick with an unusual condition called angel wing. It would have died if it hadn’t been rescued. Fortunately the young bird fully recovered at Red Creek Wildlife Center and was released on Monday, 12 August 2019 at Middle Creek WMA.

Most of the story is told in this video on Red Creek Wildlife Center’s Facebook page. Here’s a little more information from PA Game Commission Peregrine Coordinator Art McMorris who took the video.

“The peregrine nest on the Market St. Bridge in Williamsport is in a location that’s very difficult to see. Members of the Lycoming Audubon Society monitor the nest and on June 9 they saw a nestling, the first evidence that the peregrines were even nesting this year.

“On June 15 Bobby Brown got a photo of the nestling, near fledging age; the photo showed defective feather development on its left wing. This couldn’t be seen when looking at the bird with binoculars or scope. In that condition, if it tried to fledge, we feared it would spiral like a maple seed and end up in the river, so a rescue mission was hastily organized.

“PennDOT District 3 provided a snooper crane, and on June 19, with a storm rapidly blowing in, PGC’s Dan Brauning, Sean Murphy and Mario Giazzon rescued the bird from the bridge and took it to Red Creek Wildlife Center.

“On the video, Peggy Hentz of Red Creek describes the bird’s condition, prognosis and treatment with the help of Radnor Veterinary Hospital. In early August the bird was ready for release so on Monday August 12, Peggy brought it to Middle Creek, Patti Barber banded it and attached a Motus nanotag, and we released her. A great success story all around!”

Click here to watch the video on Red Creek Wildlife Center’s Facebook page. (You don’t have to be on Facebook to see it.)

p.s. You may be wondering: What is angel wing?

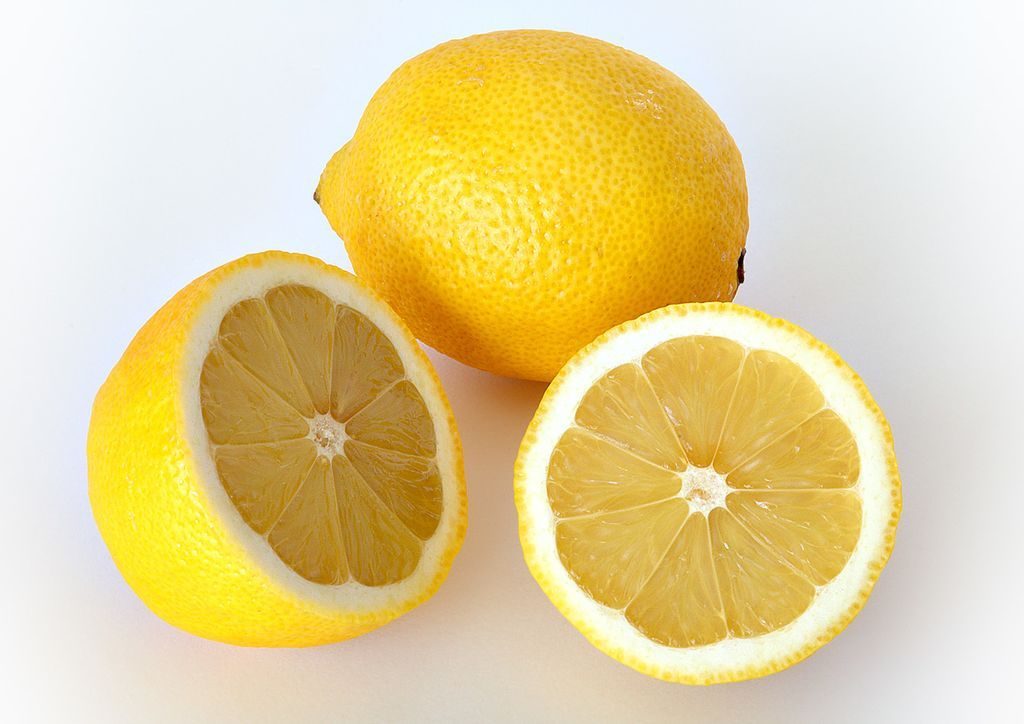

As Peggy Hentz explains in the video, angel wing is a syndrome normally seen only in ducks and geese, especially those fed a poor diet. (Bread is the usual cause of angel wing.)

The syndrome is acquired in young birds while forming their wing feathers and can be treated in rehab if caught early. It’s incurable in adults.

In the photo below, this muscovy duck has angel wing. The last joint on both wings is twisted and the deformed (white) feathers point out instead of lying flat against the body. Like all birds with angel wing, this duck cannot fly. It will lead to his early death.

(screenshot from video at Red Creek Wildlife Center Facebook page; angel wing photo from Wikimedia Commons; click on the captions to see the originals)