If I had to pick a Best Bird on my trip to Alaska it would be the long-tailed jaegar (long-tailed skua, Stercorarius longicaudus), the most graceful arctic predator.

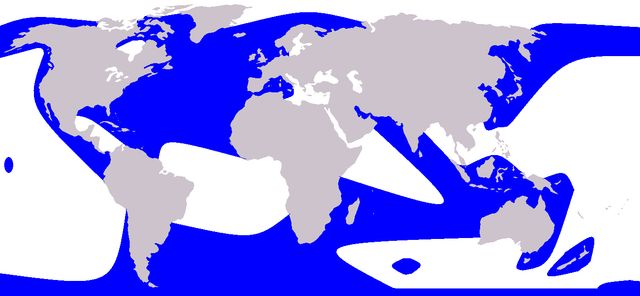

Long-tailed jaegars are the smallest of skuas, a genus of predatory seabirds that range from pole to pole. In flight their long tails and flowing movements remind me of swallow-tailed kites as they float over the tundra in pairs and loudly defend their territories. On the hunt they can hover like kestrels, as shown in the video below.

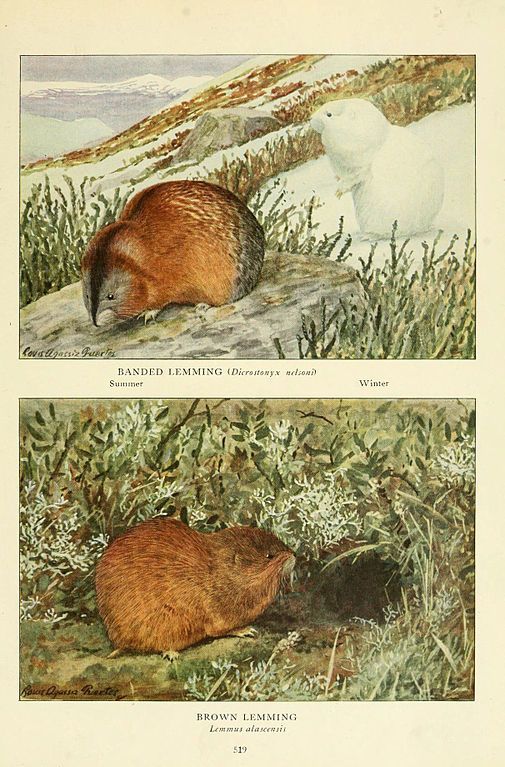

Though long-tailed jaegars are seabirds, their favorite foods in Alaska are collared lemmings.

How does a seabird without talons capture rodents? Well, he doesn’t use his feet.

Birds of North America Online explains his hunting technique …

Long-tailed Jaeger hunts these lemmings by hovering or poising in a headwind at height of 1-10 m [3-30 feet] (usually about 4 m) above tundra, like a kestrel unlike other jaegers, and by watching from perches on small rises or frost mounds … Having detected prey, often pursues it on foot and pecks it until it is dead; never uses feet to capture prey.

Birds of North America Online

Though both sexes can incubate, the male long-tailed jaegar spends two thirds of his time hunting for his mate while she warms the eggs.

We could see her white chest far away on the tundra, waiting for her graceful mate to come home.

(photos by Gregory “Slobirdr” Smith, Allan Hopkins and from Wikimedia Commons. Click on the captions to see the originals.)