This morning, 16 March 2019 around 10am, Hope laid her third egg of the season. Since she usually lays four eggs I expect she will begin incubation now.

(photo from the National Aviary falcon camera at University of Pittsburgh)

This morning, 16 March 2019 around 10am, Hope laid her third egg of the season. Since she usually lays four eggs I expect she will begin incubation now.

(photo from the National Aviary falcon camera at University of Pittsburgh)

If you like to watch the seasons change take some time to go birding this weekend. Ducks, robins and blackbirds are on the move.

Last Tuesday at Moraine State Park, my friends and I saw 16 species of waterfowl including tundra swans, three kinds of mergansers, a rare red-throated loon, and ruddy ducks like the one pictured above. (Notice his breeding plumage, blue bill.)

Migrating species change as you travel east. Last Tuesday at Yellow Creek State Park — only 70 miles east — there were 855 canvasbacks! We didn’t see any at Moraine.

Meanwhile American robins are arriving in good numbers. They sing at dawn in my neighborhood even though they haven’t reached their destination. Pretty soon they’ll be singing in the dark, too.

Watch for red-winged blackbirds, common grackles and killdeer. They’ve just arrived in Pittsburgh.

(photos by Lauri Shaffer, Birdingpictures.com)

Every spring we wonder where Downtown Pittsburgh’s peregrine falcons will decide to nest. Thanks to Lori Maggio’s recent observations and photos, we’re pretty certain they’ve chosen their favorite site at Third Avenue. We also think this pair is still Dori and Louie (more on that later). Here’s the news from the past two weeks.

Above, the Louie perches at the Third Avenue nest ledge on February 28. Below, the pair sits atop Point Park University’s Lawrence Hall.

Someone perched on a Lawrence Hall window ledge. I wish that bird was outside my window!

On March 1, Louie waited on the “rescue porch” railing while Dori was inside the nest area.

Lori snapped the following two photos while she walked across the Smithfield Street Bridge. Yes, you can see a peregrine standing in the nest area from that distance! Lori zoomed her camera.

On March 8 Louie was perched at the nest ledge and flew away.

Lori’s observations and photos helped us decide that these birds are still Dori and Louie because …

Here’s another photo of the ruffled-looking male. He looks like Louie to me.

p.s. In case you missed it, we knew the peregrines wouldn’t nest at Gulf Tower this year because of roof construction. The nestbox was removed (temporarily) in January; the Gulf Tower camera is not operational. Gulf Tower will install a new nestbox when construction is completed. For more information read No Nest at Gulf This Year.

(photos by Lori Maggio)

Seven years ago I wrote about the beautiful white eye ring on a bird named the silvereye (Zosterops lateralis), native to Australia and New Zealand. In Hawaii I saw a similar bird, the Japanese white-eye (Zosterops japonicus).

They’re different species in the same genus, Zosterops.

It turns out there are 100 species in the Zosterops genus (minus three recently extinct). They range from Africa to India, Southeast Asia, China, Japan, Australia and many islands in the Indian and Pacific oceans.

These versatile little birds — only the size of a chickadee — usually arrive at new locations on their own. They showed up in New Zealand in 1832 and 1856, presumably blown east in a storm from Australia.

Humans helped white-eyes get to Hawaii. We introduced Japanese white-eyes to Oahu in 1929, but these resourceful little birds have now spread to all the other Hawaiian Islands.

Wherever they go, Zosterops tend to differentiate themselves quickly and become new species. Maybe the Japanese white-eye in Hawaii will morph into the “Hawaiian white-eye” in a few hundred years.

See more about the silvereye in this vintage blog: Eye Ring.

Thursday morning, 14 March 2019 at 2:30am, the female peregrine at the Cathedral of Learning laid her second egg.

The snapshot below shows Hope just after she laid the egg, holding her feathers away to allow it to dry.

Watch the Pitt peregrine nest on the National Aviary falconcam.

p.s. Thank you to Luann Walz for alerting me to this event.

(photos from the National Aviary falconcam at Univ. of Pittsburgh)

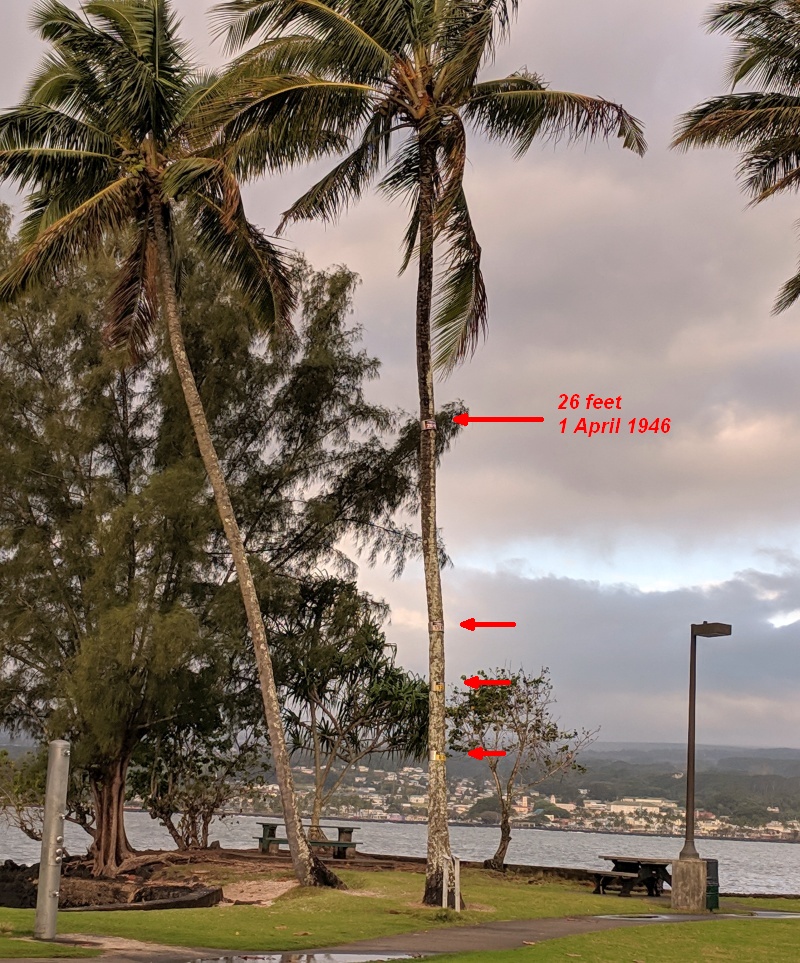

In Hilo, Hawaii there’s a palm tree in the city’s bayside park with metal rings on its trunk. Each ring is marked with a year and the height in feet. The highest one (arrow on my photo above) says “26 feet, 1946.” It memorializes a tsunami that spawned the Pacific Tsunami Warning System.

Tsunamis, sometimes called tidal waves, are seismic sea waves caused by earthquakes, underwater landslides or explosions. They happen when the ocean is abruptly displaced, as shown in this tsunami animation.

In the wee hours of 1 April 1946 a massive underwater earthquake struck offshore in the Aleutians near Unimak Island, Alaska. It was so massive that it created a 114-foot wave that swept away Unimak’s new lighthouse. The rest of it raced across the Pacific Ocean at 500 miles per hour and hit Hilo five hours later around 7am.

Hilo had no idea the tsunami was coming. Some people were mesmerized as the bay sucked loudly out to sea and exposed floundering fish. When the water returned in five surging waves, the highest was a 26 foot wall of water. Everyone ran away. 159 people died. The town was destroyed. (Note the wave in the background of this photo taken as the tsunami arrived in 1946.)

The palm tree was there when it happened. The 26-foot marker shows the debris line left by the 1946 tsunami plus three other large tsunamis that passed the tree: 15 feet in 1960, 12 feet in 1952 and 8 feet in 1957. This video from September 2018 explains the markers (starting at the 1:19 timemark with the narrator’s face).

The following video shows After and Before photos taken in 2010 and taken at the moment the tsunami hit the trees.

Ultimately, the disaster had a positive outcome. By 1949 the U.S. had installed a warning system, now called the Pacific Tsunami Warning Center, to detect earthquakes and warn of potential tsunamis. Throughout Hawaii you’ll see signs and sirens to tell you where to evacuate and when to leave.

It was a terrifying 26-foot wall of water but it led to a safer future.

(photo credits: palm tree by Kate St. John, 1946 photo from Wikimedia Commons, videos by Aaron and by the Center for the Study of Active Volcanoes, Warning sign and siren from Hawaii Emergency Management)

With 10,000 species of birds on earth, there’s a lot of variety in their methods for nesting, incubating eggs, and raising young. You can see this on the Hays bald eaglecam and the Cathedral of Learning peregrine falconcam, now that there are eggs in both nests. Here’s what we’ve seen already.

Bald eagles …

Peregrine falcons …

The photo above shows Hope perched at her nest before dawn without “sitting” on her first egg. Even though the temperature was close to freezing at the time, she didn’t have to keep the egg warm because she hadn’t begun incubation.

And here’s Terzo guarding the egg while Hope eats breakfast.

If you’re used to nesting robins, chickens and bald eagles, peregrines are certainly different.

Watch the Cathedral of Learning peregrines on the National Aviary falconcam. For more cool facts about them see my Peregrine FAQs.

(*) Incubation is when the bird opens its belly feathers and lays its bare skin against the eggs to heat them. Constant warmth is required for the embryo to develop.

(photos from the National Aviary snapshot falconcam at Univ of Pittsburgh)

Monday, 11 March 2019:

This afternoon at about 5:22pm Hope, the female peregrine falcon at the Cathedral of Learning, laid her first egg of the season.

Here she is in two snapshots, above and below.

Every year she lays an egg approximately every other day until she reaches a total of four. Expect her next egg on March 13.

Watch her on the National Aviary falconcam.

(photos from the National Aviary falconcams at University of Pittsburgh)

11 March 2019

Have you ever wished for a tool that could accurately count a single bird’s voice among dozens of singers? You aren’t alone. Ornithologists are eager for a way to census birds using field recordings, but the sheer volume of data and complexity of bird song makes this a daunting task. A free tool that can identify huge volumes of song data doesn’t exist yet, but the Kitzes Lab at the University of Pittsburgh is creating one.

In December 2018 Assistant Professor Justin Kitzes of the Department of Biological Sciences won an AI for Earth Innovation Grant, awarded by Microsoft and National Geographic, to develop the first free open source model for identifying bird songs in acoustic field recordings. Its name is OpenSoundscape.

OpenSoundscape uses machine learning, a subset of artificial intelligence (AI), to scan recorded birdsong and algorithmic hunches to arrive at a song’s identity. To do this the Kitzes Lab starts with real life recordings.

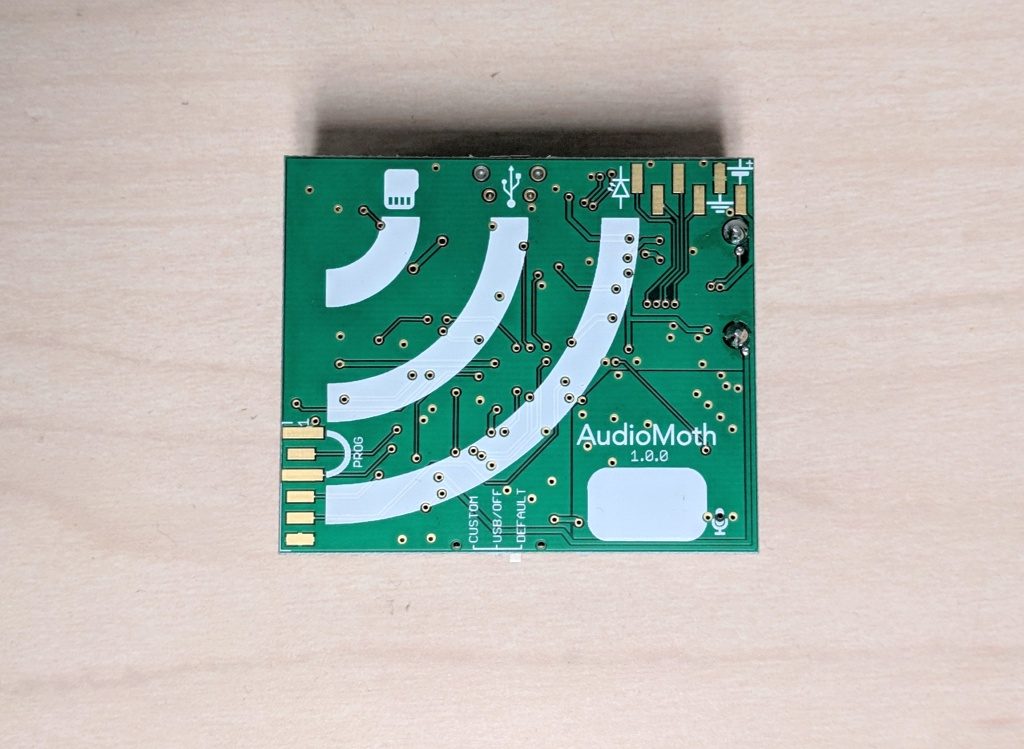

The team places small AudioMoth recorders in an array in the forest, much the same way human observers do point counts except that the Audio Moths are all recording at the same time.

The team brings the recorders back to the lab and downloads the sound files to the database. (Some day the software will be able to triangulate GPS from several Audio Moths and determine a single songbird’s location!)

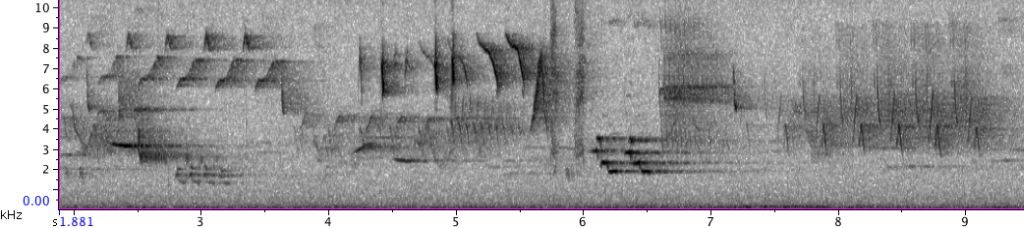

Here’s one recording of at least six individual birds. OpenSoundscape is learning how to identify them.

It makes a spectrogram of the sound file (below), then picks out each pattern and uses algorithms and the classifier library to identify the individual songs.

The more songs it successfully identifies, the better its algorithms become.

By the end of 2019 the OpenSoundscape models, software, and classifier library of birdsong will be ready for researchers on a laptop, cloud service or supercomputer. Ornithologists will be able to gather tons of data in the field and find out who was singing.

p.s. WESA featured this project in their Tech Report on 26 Feb 2019. Click here to listen.

(credits: photo of ovenbird by Aaron Budgor on Flickr, Creative Commons license. Photo of Audio Moth on a desk by Kate St. John. All other photos and sound file, courtesy the Kitzes Lab)

At last it feels like spring is coming. Let’s get outdoors!

Join me on my first bird and nature outing of 2019 at

Duck Hollow and Lower Frick Park on Sunday, March 31, 2019 — 8:30am to 10:00am.

Meet at Duck Hollow parking lot at the end of Old Browns Hill Road.

We hope to see migrating ducks on the river and and songbirds along lower Nine Mile Run Trail in south Frick Park.

Dress for the weather and wear comfortable walking shoes. Bring binoculars, field guides and a scope for river watching if you have them.

Hope to see you there!

NOTE! Check the Events Page before you come. Construction of the new McFarren Street Bridge at Duck Hollow begins on Monday March 11. If it affects this outing I’ll let you know on the Events page.

(photo by Steve Gosser)