Among the heroes of the peregrine falcon’s restoration in North America, Tom Cade was legendary. During his lifetime peregrines went from plentiful to nearly extinct. Today their population is healthy and growing, thanks in great part to Tom Cade’s efforts and dedication. He died this month at age 91.

Tom Cade was a falconer nearly all his life. He became hooked on peregrines at age 15 when one flew close overhead on its way to capturing prey. That was in the early 1940s when the peregrine population was still healthy in North America.

By the mid 1960s Dr. Cade was the head of Cornell Lab of Ornithology, the peregrine population was in free fall, and he could see it happening. The situation so alarming that he and other raptor experts were desperately trying to find out why before it was too late.

In 1965 they convened a conference about the peregrine’s decline at the University of Wisconsin, Madison that became the catalyst for peregrine recovery. At that point they knew the decline was due to DDT and dieldrin but they had no proof. (Proof came later from Derek Ratcliffe.) Meanwhile, agricultural experts argued it couldn’t be caused by pesticides; the pesticides were so useful.

In a 2015 video on the 50th anniversary of the Madison Conference, Tom Cade told how the conference changed the peregrines’ future. The transformational moment came when Jim Rice, a renowned falconer and naturalist from Pennsylvania, spoke nine words. It changed Tom Cade’s life. See him tell the story here.

After the conference Tom Cade was key in all that happened next, especially in shaping the captive breeding program and peregrine reintroduction. DDT and dieldrin were outlawed in the early 1970s. By 1999 peregrine falcons were plentiful enough in the western United States that they were removed from the Endangered Species List.

In 1970 Tom Cade co-founded The Peregrine Fund and worked with them for the rest of his life to conserve raptors around the world. See their tribute and remembrance video here.

We all stand on the shoulders of the great conservationists who went before us. We mourn Tom Cade’s loss but we celebrate his incredible contribution to conservation and to peregrine falcons.

Thank you, Tom Cade. Your inspiration lives on.

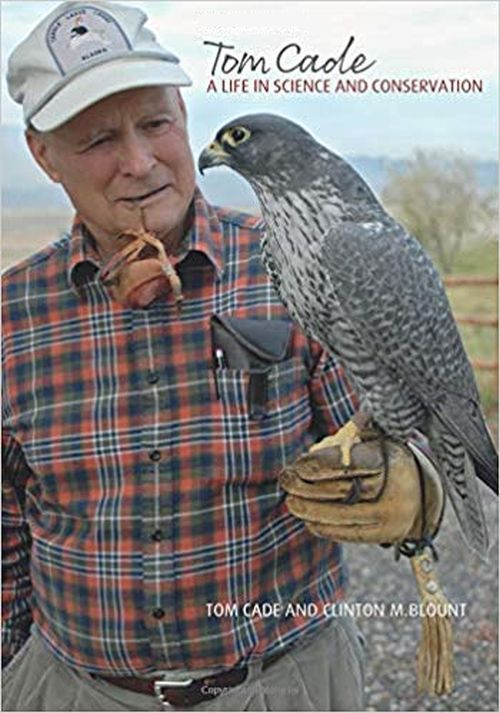

Read Tom Cade’s obituary in the New York Times. His book, Tom Cade: A Life in Science and Conservation by Tom Cade and Clinton M. Blount is available here on Amazon. The cover, which illustrates this article, shows Tom Cade with his gyrfalcon, Krumpkin, 2008.

(credits: Information on Tom Cade’s life is drawn in part from his obituary in the New York Times. photo: Cover of Tom Cade: A Life in Science and Conservation by Tom Cade and Clinton M. Blount via Amazon)