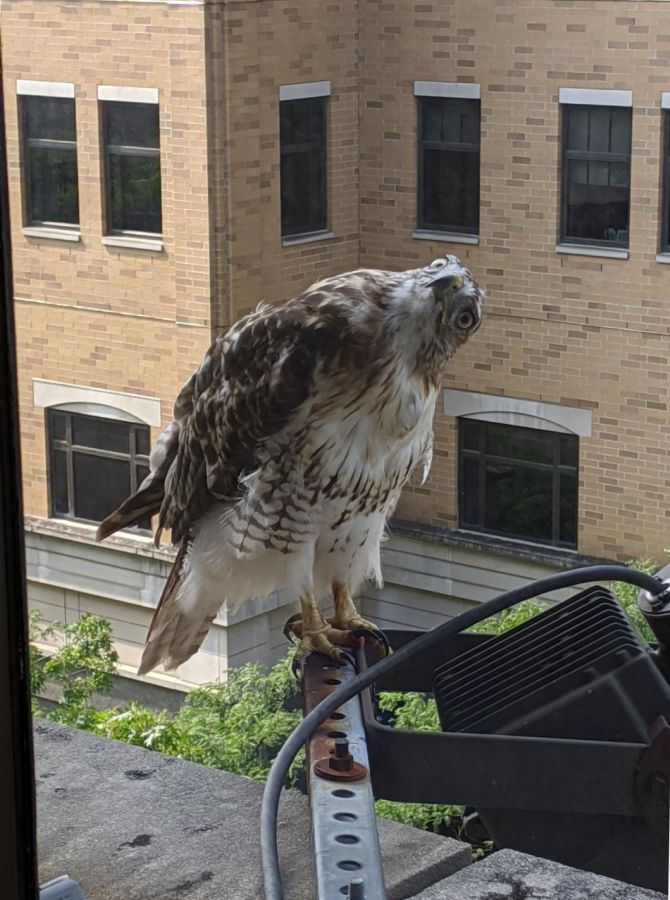

November is a busy time for raptors on the University of Pittsburgh campus. Migrating red-tailed and Cooper’s hawks pass overhead while the Cathedral of Learning peregrine pair, Terzo and Morela, watch the skies and defend their territory.

Morela is especially vigilant against red-tailed hawks. Months before we knew she was on campus, @PittPeregrines noticed a peregrine kept chasing red-tailed hawks away from the Cathedral of Learning.

- Aug 26, 2:40pm — Red-tailed hawk hovering over the 20th Century club is chased north and hit repeatedly by a Pitt peregrine.

- Sep 13, dusk — A peregrine leaps off the Oaklander Hotel and chases a red-tailed hawk, grounding it on the lawn at William Pitt Union.

Hope and Terzo didn’t bother with red-tails so something had changed. It was Morela.

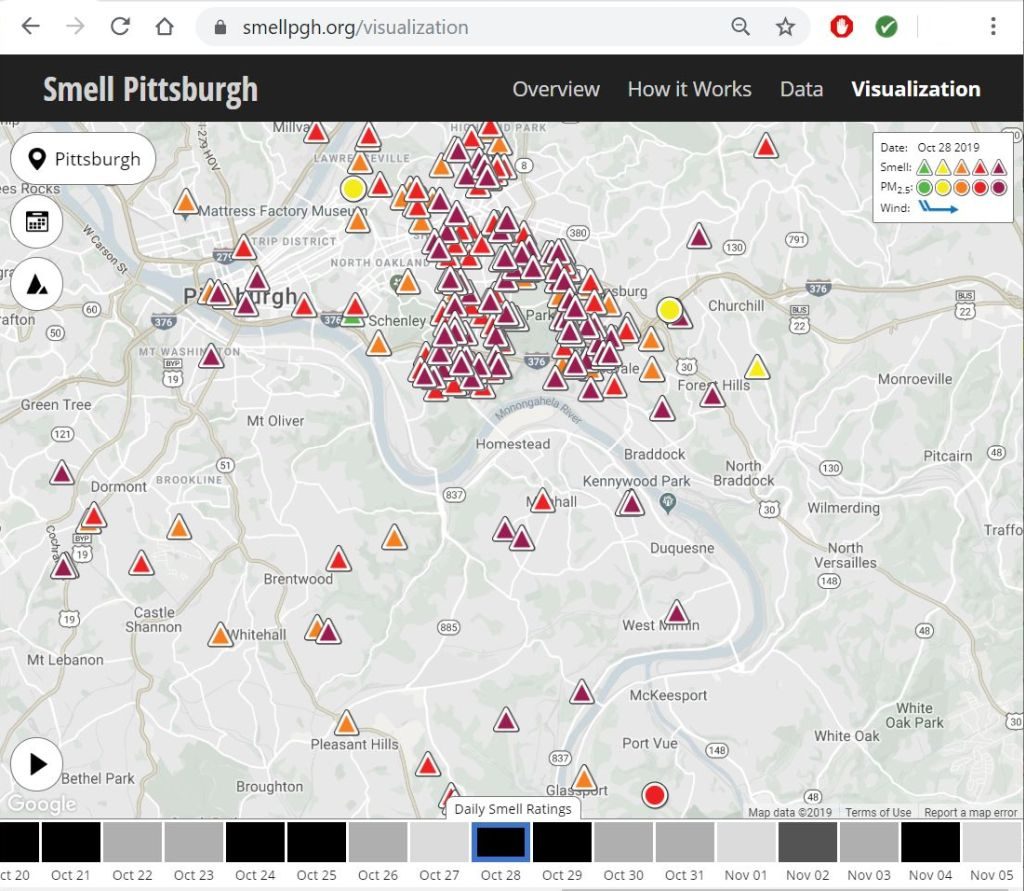

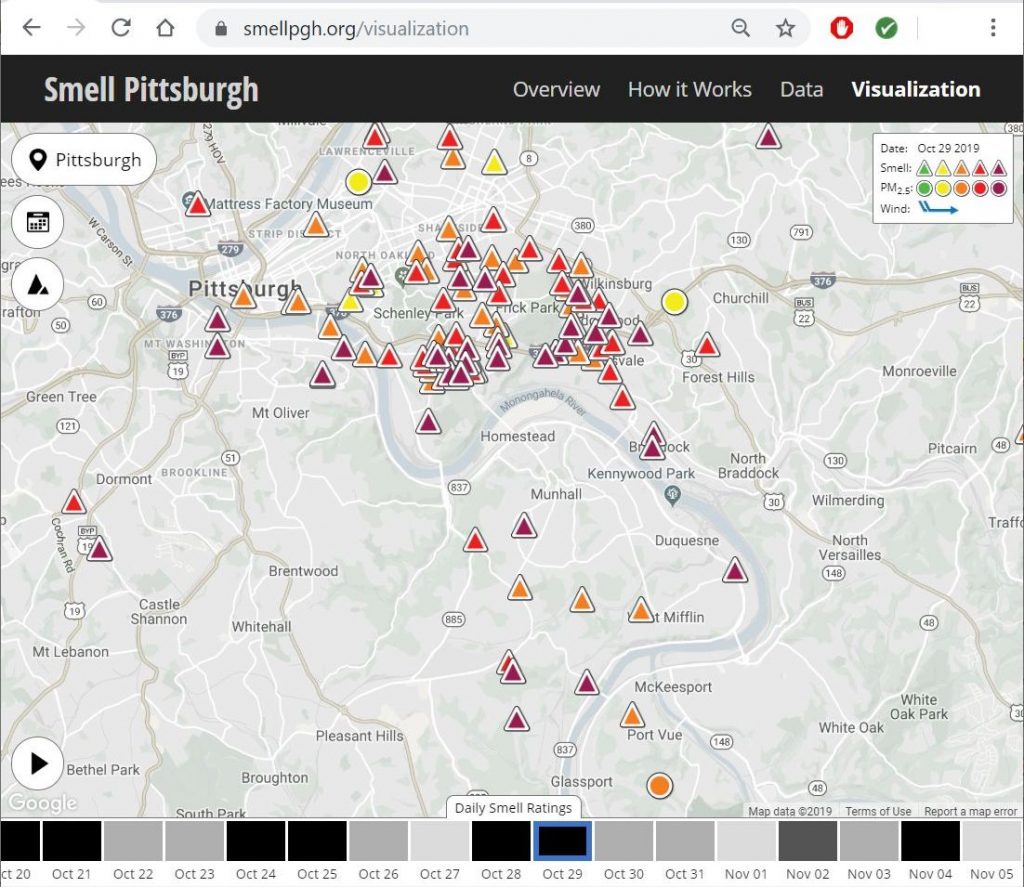

Was she involved in this incident? On Friday Nov 8, Pitt Police and a PA Game Commission Game Warden rescued an injured red-tailed hawk from the patio at Tower B. (The tweet says “falcon” but don’t worry, it’s a hawk. No news on its injury.)

Thank you to the Pitt students and PA Game Commision Game Warden who helped care for this injured falcon on Tower B’s patio yesterday. #PittPolice #h2p #Pitt pic.twitter.com/BUyIwPi2dg

— Pitt Police (@PittPolice) November 9, 2019

In their photo tweet you can see the Barco Law Building in the background. Kim Getz works there and has been keeping track of the red-tailed hawks that hang out at the Law School. She hopes the injured bird wasn’t this adult that keeps the rodent population under control …

… or this curious youngster.

By 3pm Saturday afternoon, 9 November 2019, I was sure that at least one adult red-tailed hawk was doing just fine. I watched it glide low just below tree height on its way to Frick Fine Arts while Terzo and Morela performed a courtship flight at the Cathedral of Learning.

At 4:12pm Morela made a round of her territory from Schenley Plaza to Heinz Chapel and the Cathedral of Learning.

All is calm. Morela rules.

(photos from the National Aviary falconcam at Univ of Pittsburgh, @PittPolice and Kim Getz)