6 November 2022

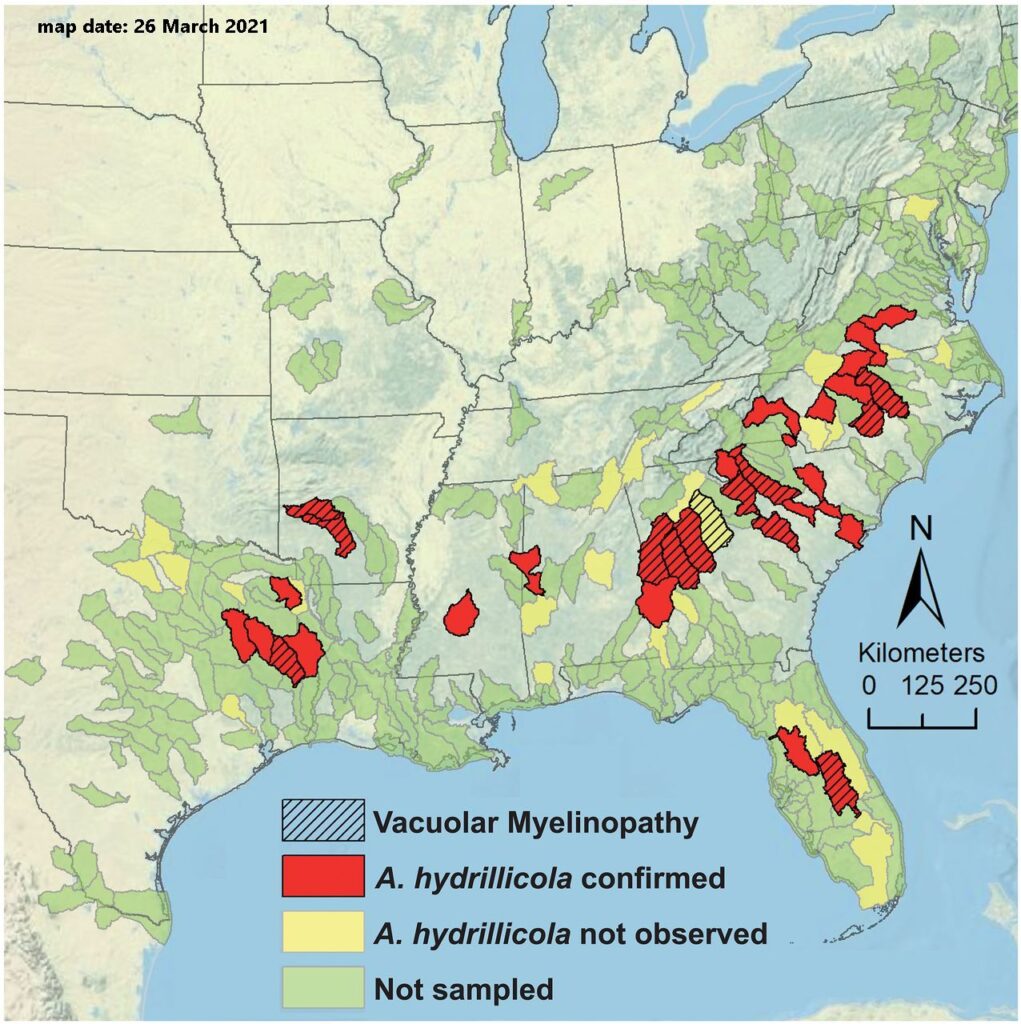

In 1994 dozens of bald eagles were found convulsing, dead or paralyzed near Arkansas’ DeGray Lake. Autopsies revealed the eagles died of a new disease called avian vacuolar myelinopathy (VM) that manifests as brain lesions. The dying spread to Florida, Georgia, the Carolinas and Texas (hashed areas on the map below) and continues to this day. In 2021 scientists discovered what causes VM. It’s a chain of events that begins when we use an aquatic weed killer to control an invasive weed.

The invasive weed is hydrilla (Hydrilla verticillata) that spreads easily and clogs waterways. It’s a huge problem in many southeastern states, especially in Florida.

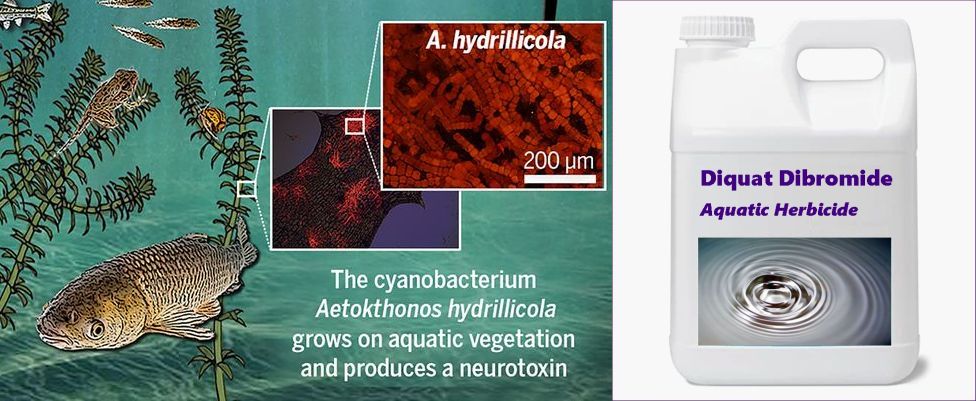

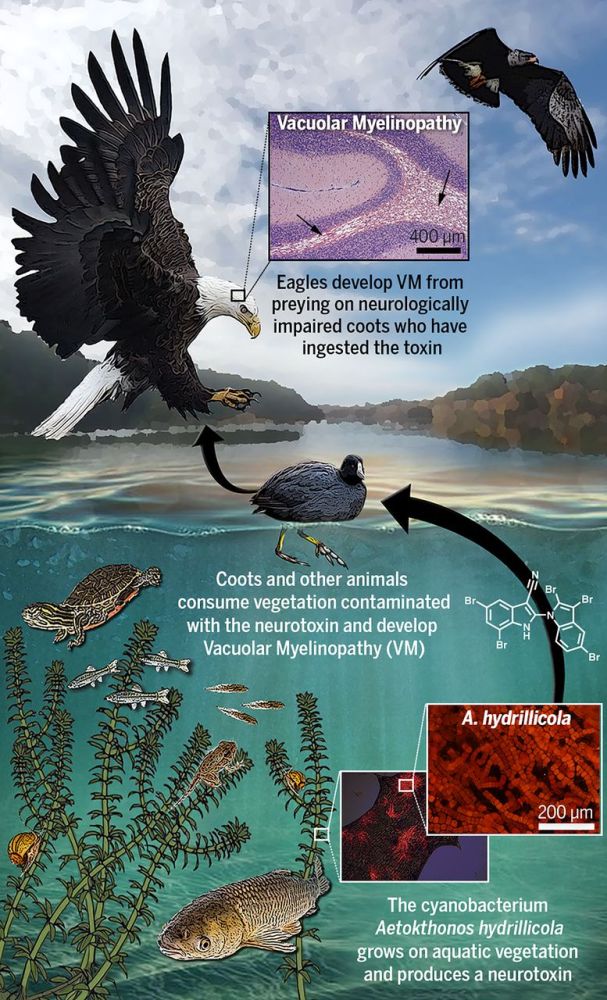

Hydrilla hosts a cyanobacteria called Aetokthonos hydrillicola which does not produce toxins by itself(*). However when it comes in contact with bromide-containing aquatic weed killer, meant to kill hydrilla, it produces a neurotoxin.

Fish and waterbirds, including American coots, eat the hydrilla and consume the neurotoxin. Soon they develop VM brain lesions.

Bald eagles and other predators eat the fish and coots, often preying on sick ones because they are easy to catch.

And so bald eagles develop brain lesions and die of vacuolar myelinopathy.

The way to stop the dying is described in this NIH article Hunting the eagle killer: A cyanobacterial neurotoxin causes vacuolar myelinopathy:

Integrated chemical plant management plans to control H. verticillata should avoid the use of bromide-containing chemicals (e.g., diquat dibromide). [The neurotoxin] AETX is lipophilic with the potential for bioaccumulation during transfer through food webs, so mammals may also be at risk.

— from NIH: Hunting the eagle killer: A cyanobacterial neurotoxin causes vacuolar myelinopathy

Thus if you use a bromide-containing chemical (e.g. diquat dibromide) to control hydrilla you will unintentionally kill bald eagles.

Other solutions for controlling hydrilla without herbicide are highlighted in Florida Today (article and video): Melbourne-Tillman harvests hydrilla to avoid herbicides.

Meanwhile bald eagles aren’t out of the woods yet because we don’t know how long it will take for the neurotoxins to clear from infected lakes.

For more information see the article that inspired this topic: Science Magazine: Mysterious eagle killer identified: A new species of cyanobacteria that lives on invasive waterweed produces an unusual neurotoxin.

(photos and diagram from Wikimedia Commons, map embedded from NIH; click on the captions to see the originals)

(*) The mystery was solved when scientists discovered that the toxin came from bromides that did not occur naturally. From NIH, Hunting the eagle killer: A cyanobacterial neurotoxin causes vacuolar myelinopathy: “Laboratory cultures of the cyanobacterium, however, did not elicit VM. A. hydrillicola growing on H. verticillata collected at VM-positive reservoirs was then analyzed by mass spectrometry imaging, which revealed that cyanobacterial colonies were colocalized with a brominated metabolite. Supplementation of an A. hydrillicola laboratory culture with potassium bromide resulted in pronounced biosynthesis of this metabolite. H. verticillata hyperaccumulates bromide from the environment, potentially supplying the cyanobacterium with this biosynthesis precursor.”

Hello Kate, I was on vacation for several weeks and am just catching up with your blog. I am wondering, if eagles die from eating birds and fish that ingested the neurotoxin, could people also be affected by the neurotoxin if they ate infected birds (maybe geese or ducks) or fish? I think that the poisoning of our waters (in this case, inadvertently) is a huge problem that not enough people are concerned about.

Mary Ann, The NIH article about “VM” disease concluded with this sobering note:

“AETX (the neurotoxin) is lipophilic with the potential for bioaccumulation during transfer through food webs, so mammals may also be at risk. Increased monitoring and public awareness should be implemented for A. hydrillicola and AETX to protect both wildlife and human health.”