6 December 2022

We humans used to think we were very special and very smart because we had language while other species did not. When we learned that other animals had language too our hubris diminished slightly but we still believed in our uniqueness: We were the only species that could think recursively.

In The Recursive Mind (Princeton University Press, 2011) Michael C. Corballis describes “a groundbreaking theory of what makes the human mind unique.”

The Recursive Mind challenges the commonly held notion that language is what makes us uniquely human. In this compelling book, Michael Corballis argues that what distinguishes us in the animal kingdom is our capacity for recursion: the ability to embed our thoughts within other thoughts. “I think, therefore I am,” is an example of recursive thought, because the thinker has inserted himself into his thought. Recursion enables us to conceive of our own minds and the minds of others. It also gives us the power of mental “time travel”—the ability to insert past experiences, or imagined future ones, into present consciousness.

— Princeton University Press Book description: The Recursive Mind

Our uniqueness suffered another blow last month when a study published in Science Advances revealed that crows can think recursively, too.

What is recursive thinking and how did crows prove they can do it?

Recursive thinking means “embedding thoughts within other thoughts” like nested Russian dolls.

For instance, my sentences are often recursive. If you put parentheses around the complete embedded thoughts they can be thrown away without hurting the sentence. As in: “Our uniqueness suffered another blow last month when a study (published in Science Advances) revealed that crows can think recursively, too.”

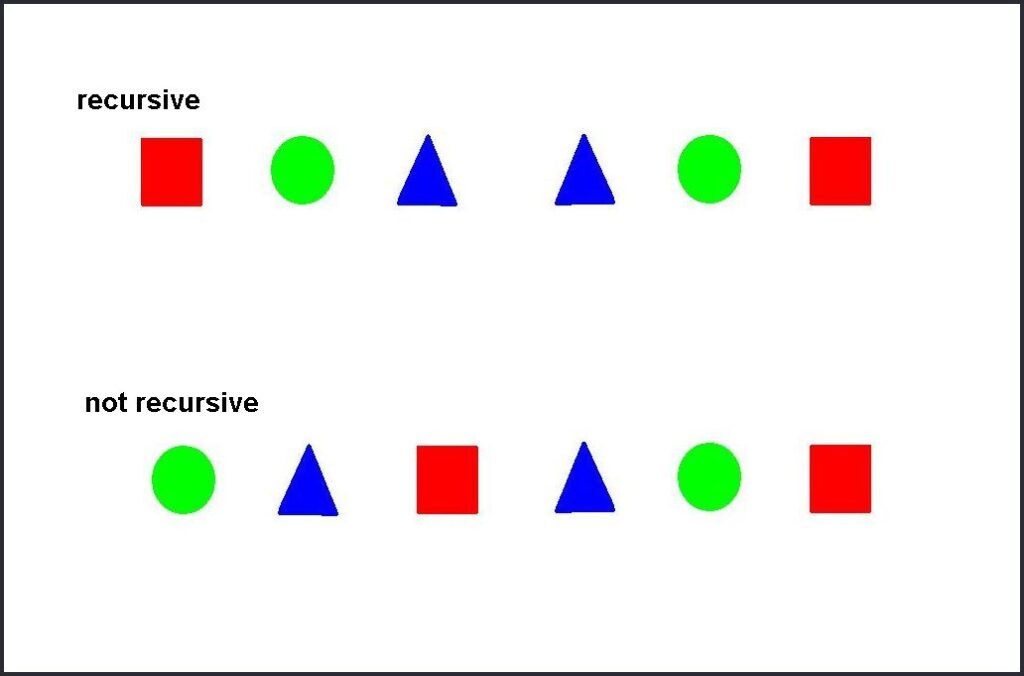

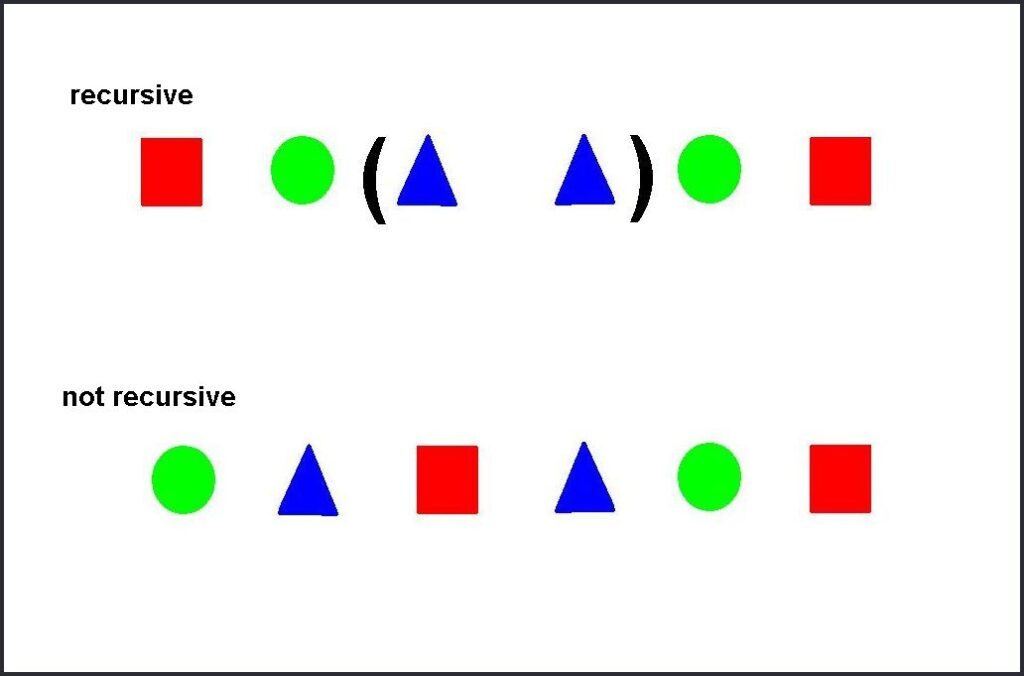

To test the birds researchers trained two crows to peck pairs of brackets in a center-embedded recursive sequence. They used differently shaped brackets, some in proper order, some not. Like this:

[ { () } ] or { ( [ ) } ]

The brackets make my head hurt. It’s easier to see in this diagram.

If you put brackets around the starting and ending “thoughts” you’ll see a pattern. The brackets fail in the non-recursive example.

According to Scientific American, after the crows were trained to peck bracket pairs, the researchers tested the birds’ ability to spontaneously generate recursive sequences on a new set of symbols. The birds were successful about 40 percent of the time, on par with 3 to 4 year olds in a 2020 study. The crows were better than monkeys who needed extra training to reach that level.

So another unique human trait is toppled by Corvids.

Hooray for crows and ravens!

p.s. Not all the scientists agreed with the study’s conclusions. Read more at Scientific American: Crows Perform Yet Another Skill Once Thought Distinctively Human.

(photos from Wikimedia Commons, diagrams by Kate St. John. Click on the caption links to see the originals)

What if the crows just preferred symmetric patterns, like they do shiny things and trinkets?

Apparently the real clincher is that they built them on their own.

Not surprising but I’m a big fan. Thank you for a crow post Kate!

My local rooks and crows will go about their day, possibly foraging, and although i will see and hear a single bird I will hear a number of calls from unseen birds. I interpret this in human terms as them calling to know the whereabouts of their colleagues. Thus one could say they call in a bracketed way, ie in relation to the other birds, in relation to themselves as individuals. This self referring phenomena is recursivity, expressed through their spoken language, but as embodied cognition. It is sensory.

So wrote this poem

The Song of the Crow

I is Croci

I sing my name

I am not me

I am we

I am all Crow

We all croak I

We rehearse

We recurse

All thee that are not Crow

You go

We flow

We flew

Liquid as the air

One river

Called Croci

One black Crow

One black flow

We go

We sing

The singular song

Of flow of us Crow

I is Croci

I sing my name