16 March 2025

When a female peregrine is getting ready to lay eggs she spends the night at the nest ledge. As egg laying becomes imminent she doesn’t have far to go to crouch over the scrape.

Last night Carla spent five hours at the nest and, from the start Ecco encouraged her to do so.

This Day-in-a-Minute timelapse video shows nest activity from 10:30 on Saturday night through 7:00am Sunday morning, 15-16 March, as follows:

- 15 March 2025: The nest is empty from sunset until 10:30pm, not shown in the video.

- When Ecco arrives he pops in and out so fast that you might not realize it’s him. Carla arrives soon after.

- Carla stands on the gravel or the green perch for most of the night; she leaves at 4:40am.

- A few minutes later Ecco arrives, checks the scrape and spends a while on the green perch.

- Ecco leaves near dawn.

The real time video clip below shows the most interesting segments. With audio on you can hear Carla calling before she leaves the nest, perhaps wailing to Ecco for a snack. After a short gap with no peregrines, Ecco comes to the nest.

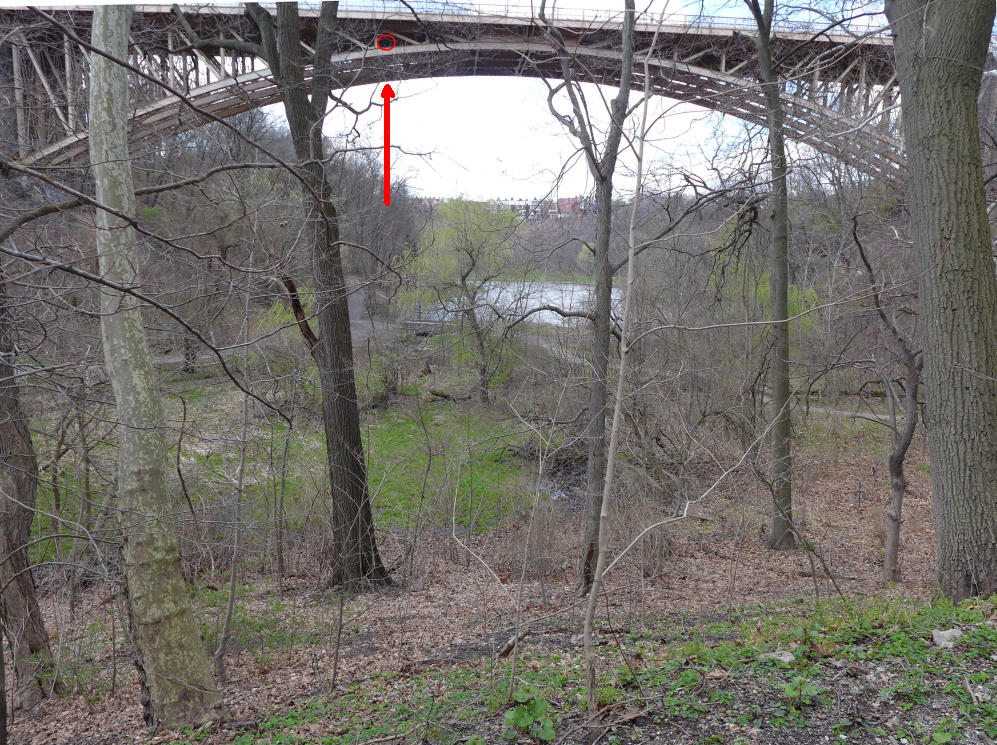

Fingers crossed we’ll see the first egg this week. Watch for it at the National Aviary falconcam at the University of Pittsburgh’s Cathedral of Learning.

p.s. Nighttime activity is not unusual among peregrines. Fifteen years ago Louie was famous for it at the Gulf Tower. See Remembering Louie: 2002-2019