Last week I told you why museum collections are valuable. Today I’ll show you what’s in them.

Bird collections are like libraries. Instead of books on shelves, they have study skins in drawers.

These two drawers at Carnegie Museum contain study skins of the scarlet tanagers collected in western Pennsylvania from 1879 to 1995. The drawers are partly obscured but together they hold approximately 100 Piranga olivacea study skins collected during a period of almost 120 years. The average speed of collecting was very slow: less than 1 bird per year in a 16,000 square mile area.

Study skins are all prepared the same way. The dead bird is skinned, the body and skeleton removed leaving the skin, feathers, beak and lower legs. It’s then stuffed with cotton and sewn up. When completed the skin is positioned on its back with wings folded and beak extended so that it fits in a drawer.

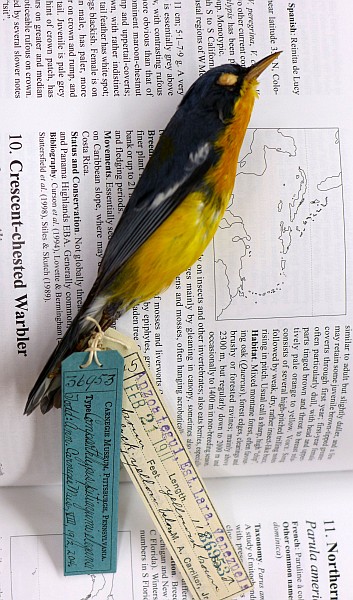

Study skins play a key role in the definition of bird species. To determine a new taxon ornithologists examine many skins. Then for each taxon one study skin on earth is chosen as the holotype for that bird, the single physical example used to describe the genus-species-subspecies.

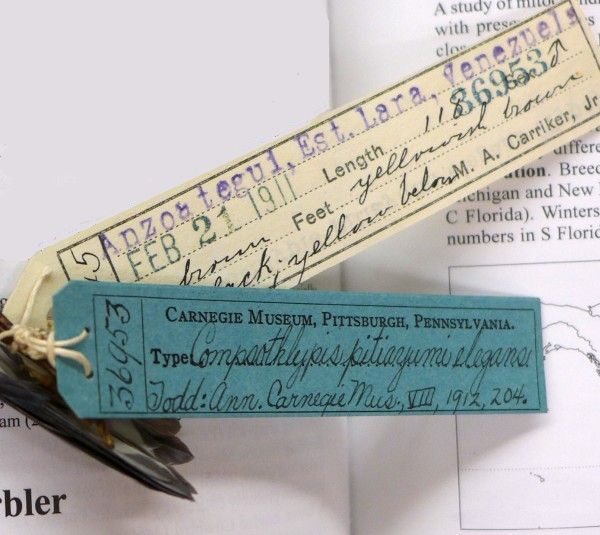

The tropical parula above is the holotype for the elegans subspecies. Housed at Carnegie Museum, it has two descriptive tags.

The white collection tag lists the specimen number, when, where, and who collected it: Number 36953, collected 21 Feb 1911 at Anzoategui, Venezuela by M.A. Carriker, Jr.

The blue holotype tag includes its scientific name, who described it, and where and when its description was published: W. E. Clyde Todd, Annals of Carnegie Museum, vol VIII, 1912, page 204. Only holotypes have the blue tag.

Because holotypes are physical examples, they can be re-examined as we learn new scientific techniques. In 1912 this bird’s scientific name was Compsothlypis pitiayumi elegans or Parula pitiayumi elegans. Since then ornithologists have learned about DNA and placed him in the Setophaga genus with the other warblers. Today his scientific name is Setophaga pitiayumi elegans.

Steve Rogers manages the herpetology and bird collections at the Carnegie and showed me how museums share their data via the iDigBio.org portal. Researchers can look up a species of interest on the website and find every study skin on earth including tag data and museum location. Here’s what the initial search result looks like for the species pitiayumi

Steve receives several requests a day from scientists around the world who need more data or want to visit the Carnegie’s collection.

Study skins are indeed studied.

(photos by Kate St. John)

How did these bird’s die?

Karen, the answer to your question is not on the label for each bird so I don’t know the answer except in general terms.

The likely answer for those collected before 1962 is here in the paragraph beneath the photo of W.E.Clyde Todd: http://www.birdsoutsidemywindow.org/2016/11/22/the-golden-age-of-collecting/

After that, collecting dropped off considerably and didn’t even occur in most years, indicating that they likely died by accident, usually a window kill.

The photo of the scarlet tanager study skins represents the death of one bird per year. Here’s a display of window-killed birds in one year, 2009, in one city, Toronto, Canada. http://www.cbc.ca/radio/thecurrent/isis-vote-fatherland-and-bird-friendly-architecture-1.2907445/up-to-a-billion-birds-die-flying-into-windows-in-north-america-each-year-better-design-could-change-that-1.2907446

Windows kill more birds now (one billion per year!) than collecting ever did.

Unbelievable!

It makes you sick to see all of the glass mirrored buildings going up. Those have to be a huge problem for the bird’s too

Hello Kate,

I was delighted to run across your blog when I was looking for a picture of study skins. I became a birder during my teenage years in the Future Scientist program at CMNH – right when Harvey Webster started out.

I’m a psychiatrist writing an article on Medium.com about labels used for mental health conditions, and comparing and contrasting that with how we categorize and name birds. Your photo of the tanagers would be wonderful to illustrate my article, especially if I can crop it to a horizontal format. May I use your photo with proper attribution?