12 July 2022

Feathers are vital to a bird’s survival but they wear out and have to be replaced by molting. The best time to do this is when feathers are not urgently needed for migration, courtship or warmth. That makes summer the time to molt. Here are a few examples.

Ruby-throated hummingbirds (Archilochus colubris), above, have to look flashy at the start of the breeding season so they molt their body feathers from June to August. On the wintering grounds they molt flight feathers in preparation for their strenuous spring migration. Look closely at ruby-throats this summer and you’ll see that their body feathers are not as perfect as they were in May.

Northern cardinals (Cardinalis cardinalis) wrap up their last brood of the season in mid summer and begin to molt in mid July. By August they will look very ragged, male and female shown below. Some will be bald.

Male and female peregrine falcons (Falco peregrinus) molt at slightly different times. Females molt their primary wing feathers while they’re incubating eggs (March-May) because their mates are doing all the hard flying to provide food. The males molt their primaries in July after teaching the young to hunt.

Birds molt the same flight feather on each side of the body so that flight remains balanced. Morela’s wings look sleek while she’s sunbathing because she replaced her wing feathers a few months ago.

However she is molting her two central tail feathers. Click on the photo below for a highlighted version showing the two growing feathers.

Meanwhile Ecco is looking very ragged (below). I saw him flying yesterday with a feather obviously growing in on each wing.

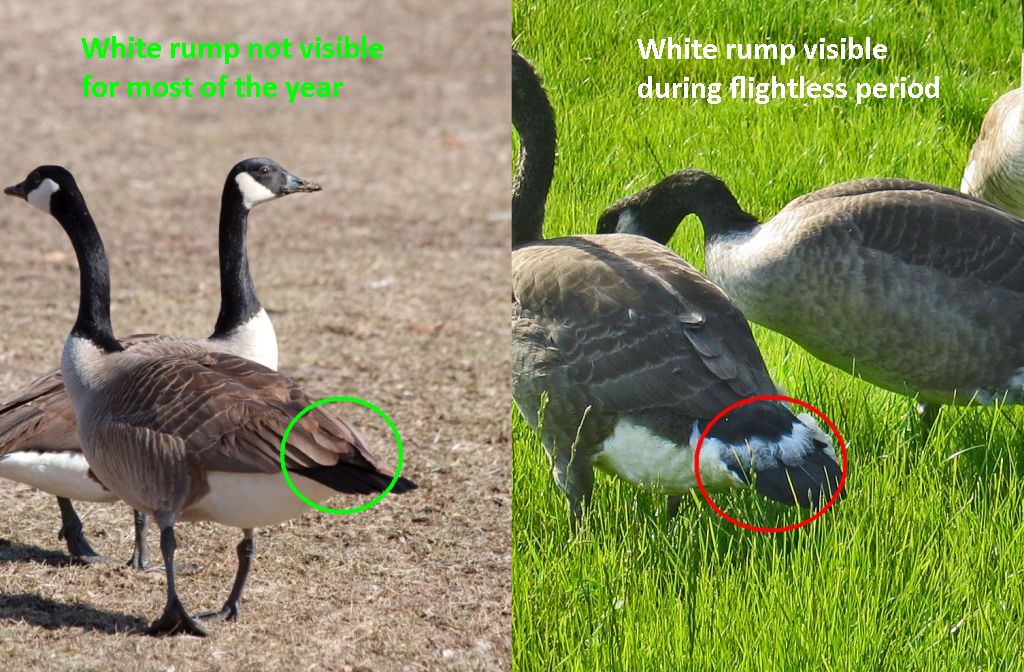

Have you noticed that Canada geese (Branta canadensis) are not grazing in their usual upland haunts? They are staying near water because they cannot fly while they molt all their primary feathers at once.

Read about their flightless period here.

For adult birds, summer is the time to molt.

(photos from Wikimedia Commons and the National Aviary falconcam at Univ of Pittsburgh)