12 November 2023

Nowadays it’s rare to write anything by hand unless it’s the size of a Post-It note. When we really want to say something we use keyboards and touch screens to generate digital text read on screens or, less often, on paper. Our writing equipment becomes obsolete so rapidly that our computers and cellphones are replaced within a decade. (Who among us is still using the same cellphone since 2013? Do we even remember what model it was?)

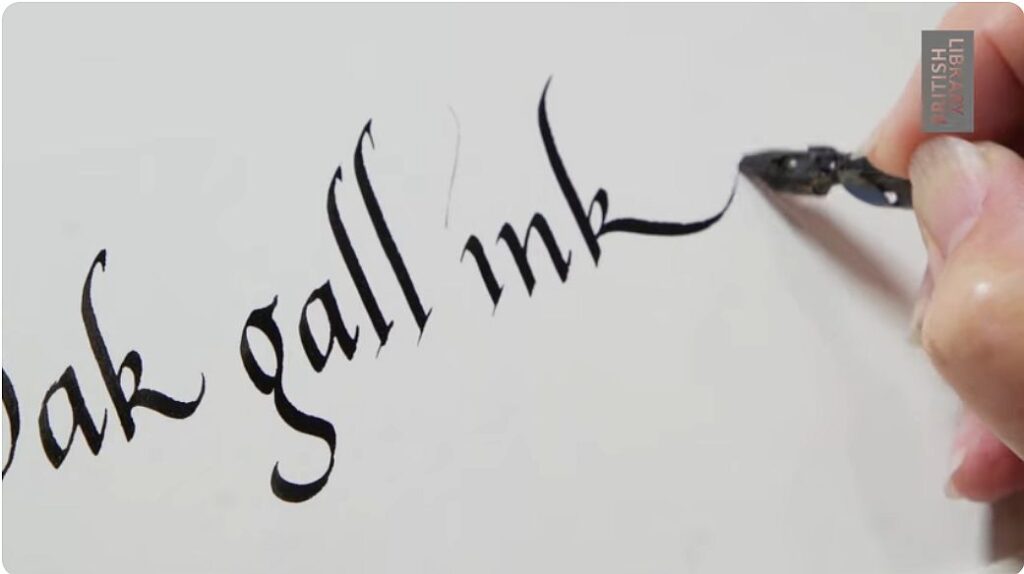

So consider this: Humans used the same writing tool, the same indelible ink, from the 5th to the 19th century. When applied to parchment, it is readable 1,700 years later. The ink is easy to make by hand from natural ingredients and is still used in calligraphy today. To make iron gall ink, the process starts with a wasp and an oak.

When a cynipid wasp lays an egg in a developing oak leaf bud, the hatched larva secretes a substance that makes the oak surround it with a gall. The wasp (Andricus kollari) and the oak marble gall below are from Europe but similar wasps and oak galls occur in North America(*).

The outer shell of the gall is rich in tannins whose presence protects the wasp from predation.

When crushed and soaked in water the galls’ tannins give color to the ink.

Two more ingredients transform the ink for final use: Iron sulfate dissolved in water makes the ink black.

Gum arabic dissolved in water makes the ink sticky enough to hold onto parchment or paper.

This video from the British Library shows how iron gall ink is made.

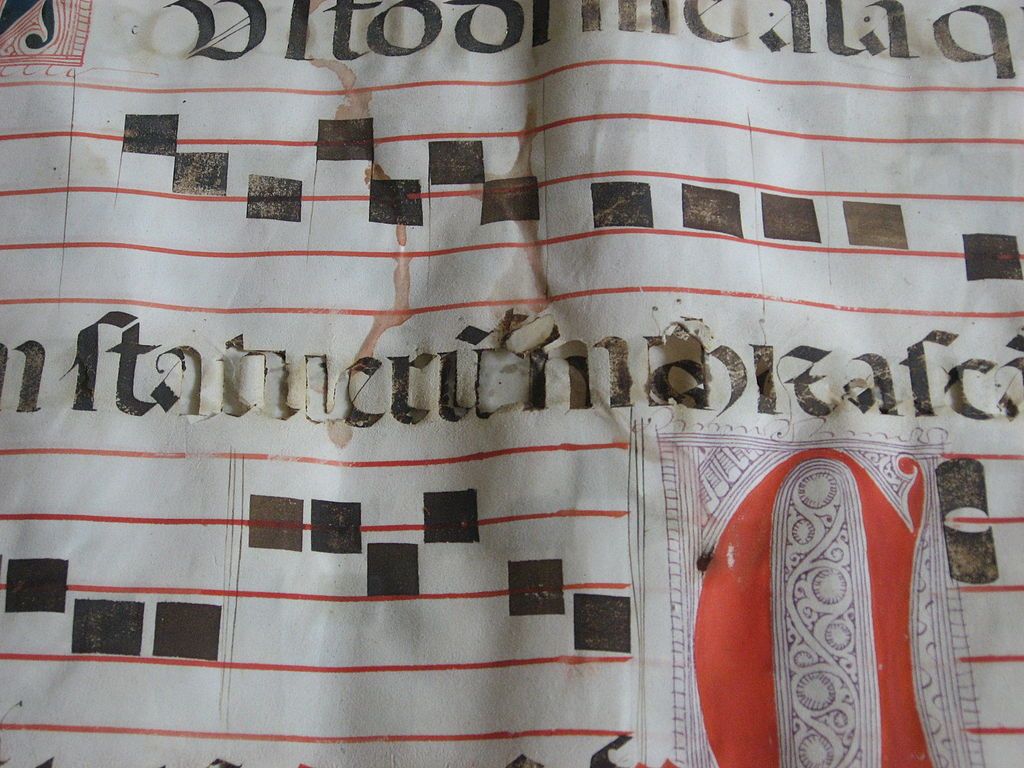

Eventually we used paper instead of parchment, even for important documents, and iron gall ink fell out of favor because the acid in iron sulfate makes the paper disintegrate. To solve that problem we invented paper-friendly inks and then computers.

Medieval manuscript creation used natural products from animals, plants and minerals. See the process from parchment to ink to binding in this 6-minute video from the Getty Museum.

Read more at Making Ink From Oak Galls: Some History & Science.

(*) p.s. The amount of tannin varies by type of gall and the tree species the gall came from. Galls with the most tannin work best.

(credits are in the captions)

Thank you for the post. Very interesting. The knowledge of ancient times is fascinating.

Thanks for posting Kate. I found this very fascinating as my Pin Oak was loaded with galls this year and last.

A belated congratulations on your 16th anniversary of writing this blog and giving your readers an insight into things we often overlook, take for granted, or have no knowledge about. It’s always a surprise to see what you have in store for us.

On another note, your blog about the piebald birds reminded me of a similar situation in humans called vitiligo where the skin loses its pigmentation.

Thanks for expanding our knowledge of what Louis Armstrong sang about—“What a Wonderful World.”

Kate, I found this fascinating as I’m reading a book about a scribe in a monastery in Europe in the early 1300’s!