22 January 2024: Day 4, Victoria Falls, Zimbabwe — Road Scholar Southern Africa Birding Safari. Click here to see (generally) where I am today.

Today we fly north from Johannesburg to the town of Victoria Falls, Zimbabwe, a distance of 574 miles (925 km) — about the same as Atlanta to Pittsburgh. I’m looking forward to my first sight of Victoria Falls, a Wonder of the Natural World.

Locally called Mosi-oa-Tunya [MOsee O TOONya] , “The Smoke That Thunders” is well named in the Sotho language. Its thundering noise can be heard 25 miles away while its mist rises to 1,300 feet. When David Livingstone was scouting the Zambezi River in 1855, looking for a trade route to the sea, guides helped him get to an island near the cliff edge where he looked down on the cascade and named it for Queen Victoria — Victoria Falls.

While it is neither the highest nor the widest waterfall in the world, the Victoria Falls is classified as the largest, based on its combined width of 1,708 metres (5,604 ft [more than a mile]) and height of 108 metres (354 ft), resulting in the world’s largest sheet of falling water. The Victoria Falls are roughly twice the height of North America’s Niagara Falls and well over twice its width.

— Wikipedia: Victoria Falls

Before I saw an aerial photo of the falls I thought its entire span could be viewed from a distance as we do at Niagara Falls, but it’s impossible to see the complete sheet of water from the ground because Victoria Falls plunges into a crack!

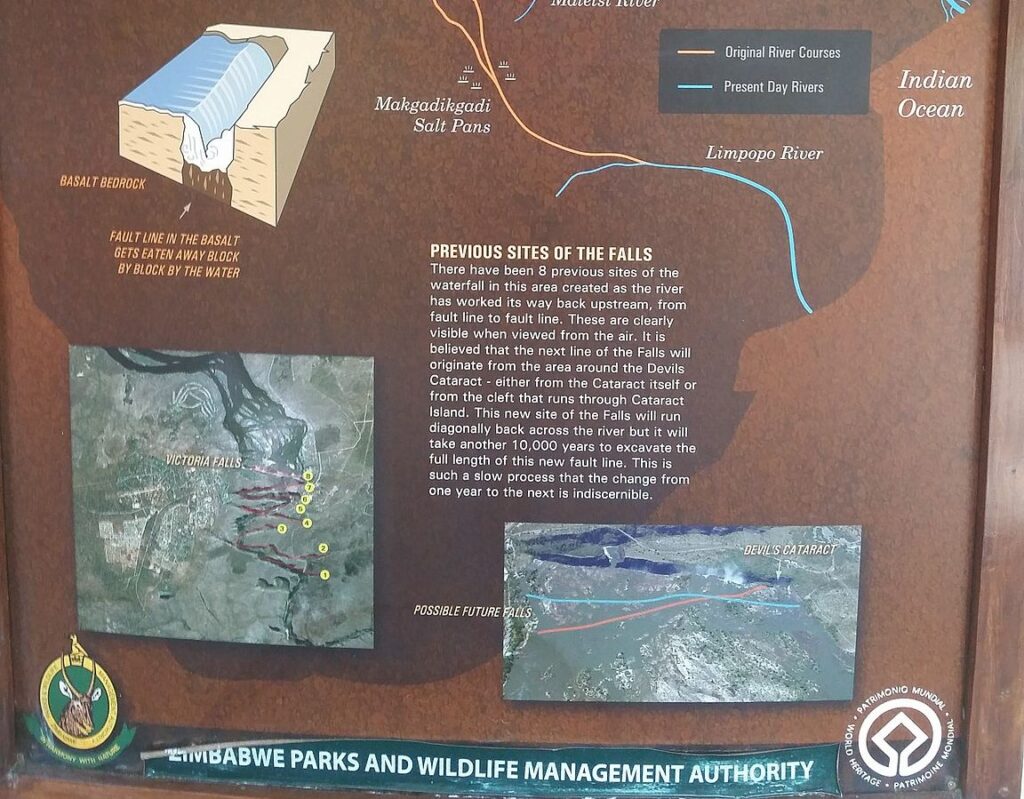

This is due to its unusual geology, illustrated on this National Park marker in Zimbabwe. Take a look and I’ll summarize it below. (I have divided it into two pieces so it is readable.)

The origin of Victoria Falls began in the Late Jurassic during the time of the dinosaurs.

- 150 million years ago a volcano erupted and poured a lake of lava at the site of Victoria Falls. The lava hardened into basalt rock. The rock cooled and cracked into fault lines.

- Sand blew in and deeply filled the faults and covered the basalt. The Zambezi River was far away as it flowed south to join the Limpopo.

- 5 million years ago the south land in present day Botswana rose up and divided the Zambezi River from the Limpopo, forcing the Zambezi to go east.

- The Zambezi eroded the sandy surface and flowed widely over the basalt. When it found a fault it fell into the crack as a waterfall.

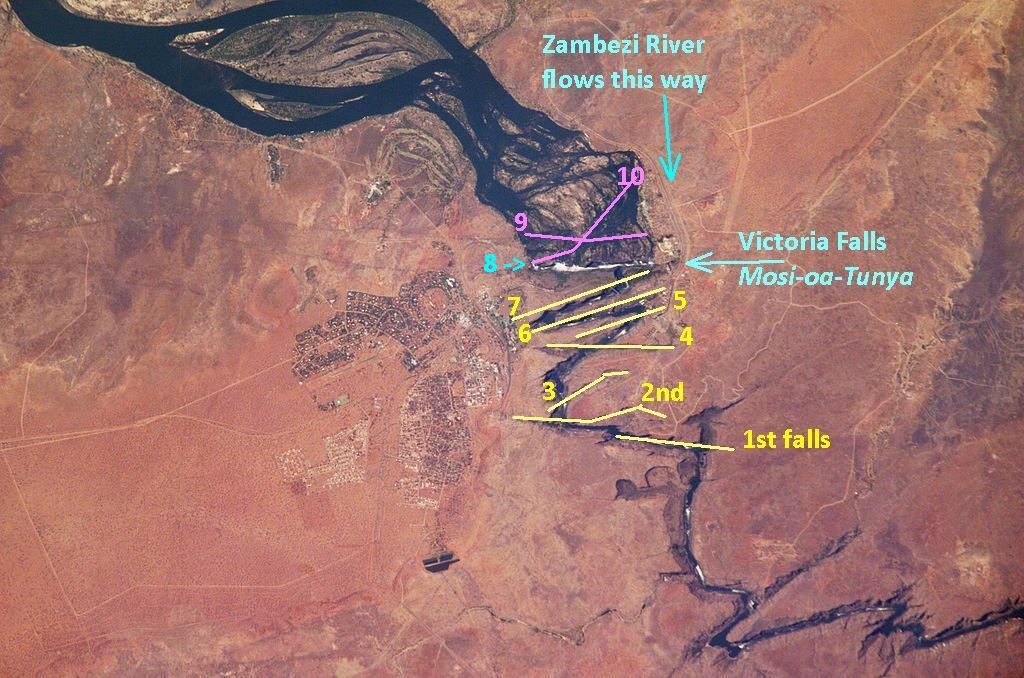

- The river is wide on the flat basalt then zigzags after the falls as it follows the fault lines, as seen in this photo from the International Space Station.

- The present day waterfall is the 8th location since the falls began. Erosion continues up the watershed. A marked up map below shows the first seven falls in yellow, the current waterfall in blue, and two future fall locations in pink.

The big question as I write this article a month ahead of time is this: How much water will be coming over the falls? October to March is the wet season so the river should be running high. However this is an El Niño year and one of its global effects is to lower rainfall in this part of Africa. So we shall see …

Five years ago the dry season in 2019 was so severe that the falls slowed to a trickle.