15 January 2025

After the big push to find Pittsburgh’s winter crow flock for the Christmas Bird Count in late December I took a break and merely enjoyed them. Searching and counting is hard work so I didn’t look for crows and if I saw them I certainly didn’t count them. Thankfully, you’ve been letting me know what you see.

Fred’s comment yesterday makes me wonder if crows are roosting on Downtown buildings.

Last Friday, 1/10/25, just before 7 am there were thousands of crows flying around and roosted in trees of the little park on First Ave downtown (across from PNC) and perched on all the buildings around. Their collective cawing would have made conversation at normal levels difficult. Having seen similar numbers in Oakland and Schenley in the early evening, made me wonder if they make the pre dawn rally to town.

— Comment from Fred, 14 Jan 2025

Frances and Sue indicate crows might be tucked in across the river at Southside.

In recent days I have noted them flying west to east over Southside Flats early in the morning (dawn).

— Comment from Frances, 13 Jan 2025

Lots of crows roosting on E Sycamore St in Mt. Washington, starting about 30 minutes ago (4:30pm).

— Comment from Sue Thompson on 8 Jan 2025

In the past two weeks I’ve noticed crows flying east to west toward Schenley Park and the Hill District and staging briefly in Schenley before dusk.

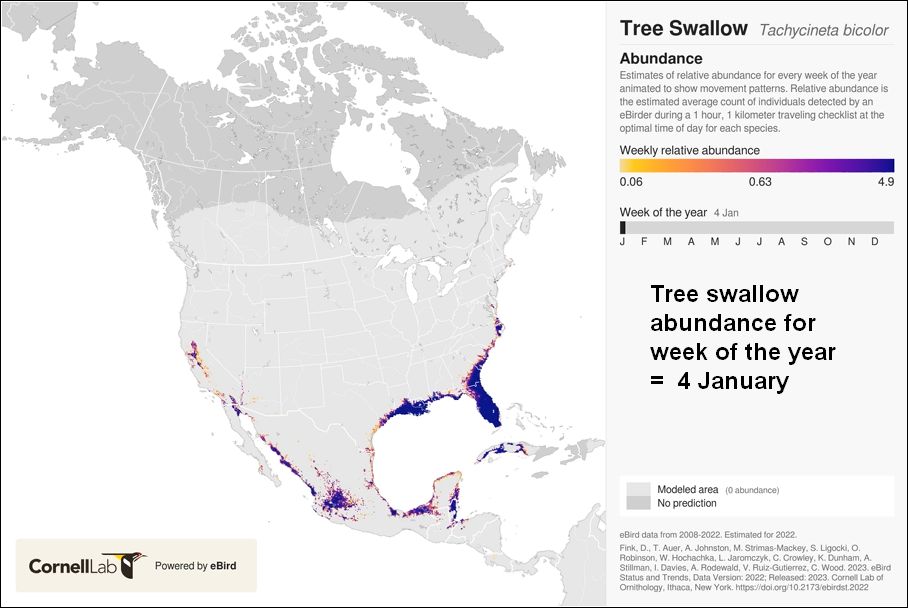

So I put these 5 observations on a map. Orange is dusk, pink is dawn, the dots are staging areas.

Pittsburgh’s crows may have split or moved their roost this month and I wouldn’t be surprised if they did. Bitter cold temperatures like last night’s 7°F prompt crows to spend the night on a warm rooftops rather than in bare trees.

UPDATE: check the comments for additional news on 15 Jan.

And here’s a treat for crow watchers: In Lawrence, Massachusetts the Crow Patrol sees crows after dark on roofs and trees using infrared cameras. Notice how crows’ eyes glow white in infrared light. 🙂