6 January 2025

If you live in southwestern Pennsylvania you probably think red-headed woodpeckers (Melanerpes erythrocephalus) are rare birds as did I until I recorded one yesterday at North Park and eBird did not flag it. Yesterday’s red-headed woodpecker was the second I’ve seen in a week. The first was in Schenley Park during the Pittsburgh Christmas Bird Count on 28 December.

The North Park bird is an all-winter visitor, hanging out with one or two others at the Elwood Shelter (40.5876006, -79.9854305) since early November 2024. It posed for Justin Kolakowski in late December.

The Schenley Park woodpecker was a One Day Wonder found by Mark VanderVen. I tracked it down when I heard his rattle call, similar to this recording of two birds interacting.

Red-headed woodpeckers are still unusual enough in Pennsylvania to attract a small crowd, particularly after they were labeled “in decline” during Pennsylvania’s Second Breeding Bird Atlas (2004-2009) because their block coverage dropped 46% since the First Atlas (1983-1989).

But you don’t have to go far to see one during the breeding season. Just cross the Ohio border and keep heading west. The pair shown at top was photographed at Sheldon Marsh in Huron County, Ohio.

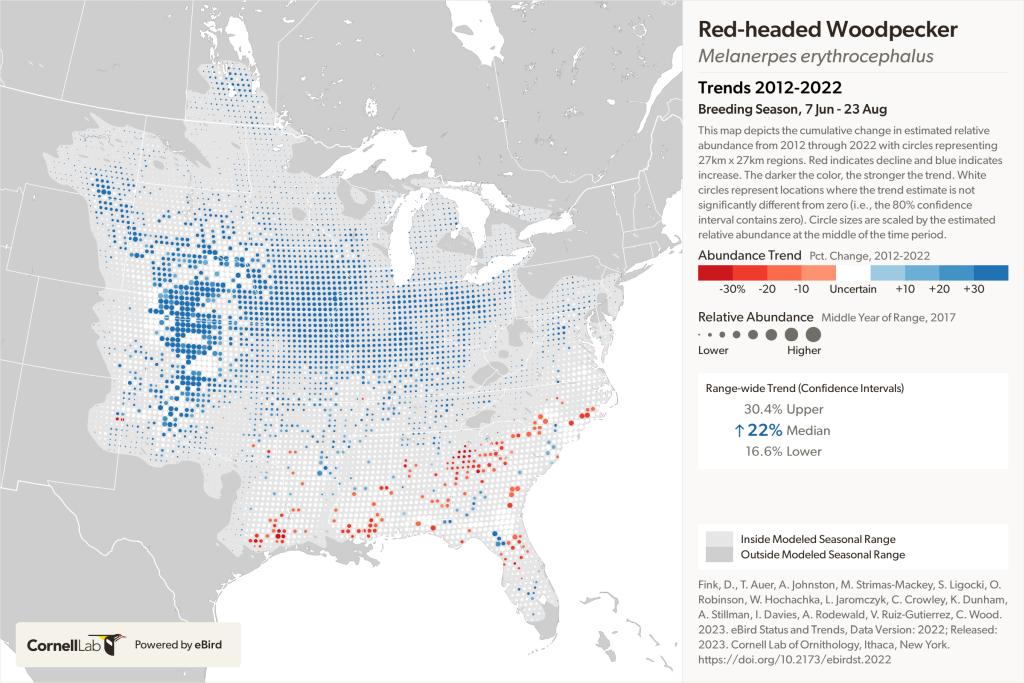

Red-headed woodpeckers are in fact increasing as their breeding population moves west. Their stronghold now is in the Great Plains. They are far less rare than we think.