10 December 2024

A sinkhole topped the news in western Pennsylvania last week when a 64 year old grandmother, Elizabeth Pollard, fell into one after sunset in Unity Twp, Westmoreland County, located 40 miles from Pittsburgh.

Ms. Pollard was last seen Monday [2 December at 5pm] while searching for her cat, Pepper, outside Monday’s Union Restaurant. She fell through the sinkhole that had “just enough dirt” for a roof system and grass to grow, Trooper Limani said.

— Post-Gazette: Crews find body of missing Westmoreland County grandmother at bottom of sinkhole

It took four days to find her body 30 feet down in the Marguerite mine whose roof and pillars are slowly collapsing after it was abandoned in 1950. It’s horrifying to think that when she stepped on a patch of grass a hole opened up and swallowed her. [More news at end.]

Meanwhile an ever-growing sinkhole began in late November in South Wales (news here) and on 4 December the Guardian ran a photo essay of sinkholes around the world.

So I began to wonder: What causes sinkholes? Where are they likely? and Why are they round? My answers will be briefly paraphrased from PA DEP, Wikipedia and USGS.

What causes sinkholes?

Sinkholes are all about water. Water drains rapidly into the ground or runs underground and dissolves the subsurface, creating a void. For a while the surface remains intact, then it collapses into the void.

Most sinkholes are caused by karst processes – the chemical dissolution of carbonate rocks such as limestone or gypsum.

Human activity can cause sinkholes, too, including:

- Groundwater pumping

- Digging, drilling or removing soil

- Water main breaks and intense concentrations of storm water

- Dams large and small

- Mining

- Heavy loads on the surface.

Where are sinkholes likely?

Naturally occurring: According to American Geosciences, the most sinkhole-prone states are Florida, Texas, Alabama, Missouri, Kentucky, Tennessee, and Pennsylvania because these have naturally occurring karst beneath the surface. Three kinds of karst are shown on this USGS map.

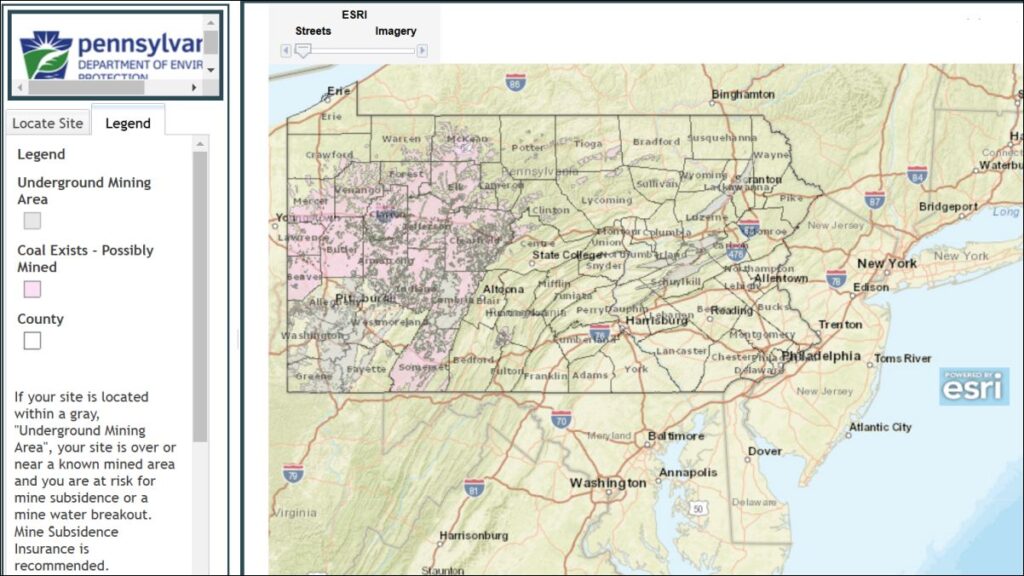

Caused by mines: Mine subsidence is a big problem for abandoned mines in Pennsylvania. As the Post-Gazette points out, sinkholes form when the old mine roof is less than 100 feet below the surface. Nowadays a coal seam just 20 feet below the surface would be strip-mined, not deep mined.

The PA DEP Mine Subsidence Insurance Risk Map shows coal and mine locations. If you live in an undermined area (gray on map), PA DEP says you should get Mine Subsidence Insurance. See the full map here at PA DEP where you can zoom in to your address and get info about insurance. Homeowners Insurance usually does *not* cover mine subsidence so be sure to check PA DEP’s Frequently Asked Questions for important information.

Why are sinkholes round?

Wikipedia says sinkholes are usually circular. Gizmodo explains why in “Ask a geologist.”

When a void occurs in sediment that has a certain amount of cohesion (‘stickiness’ among sediment grains), the most stable configuration of the roof of the void is a dome, like the dome of the U.S. Capitol building. If that dome collapses, the vertical sides may remain upright, and the open hole will be circular.

— Gizmodo: Why are sinkholes round?

Learn more about the sinkhole tragedy in western PA at:

- WTAE: Body of grandmother found in Pennsylvania sinkhole after 4-day search.

- Post-Gazette: Crews find body of missing Westmoreland County grandmother at bottom of sinkhole

- Post-Gazette: The sinkhole where a Westmoreland County woman died is unusual. But sinkholes themselves are not.

Learn the warning signs of sinkholes at the 7 Most Common Signs of Sinkholes.