9 October 2024

Yesterday while Bird Lab was at Hays Woods, Nick Liadis captured and banded a Connecticut warbler! I was not there to see this rare bird (alas) but Nick sent me a photo. Notice that the warbler has an engorged tick at top right of his eye-ring.

Tick season has returned with a vengeance after a low period during August and September’s drought. Because they cannot live without moisture ticks hang out in humid vegetation, but there was very little available during the drought. All that has changed with the recent rains and black-legged ticks are now active for their mating season which they conduct on the bodies of deer. I was reminded of this yesterday when I saw a deer in Schenley Park with three engorged ticks on its face. (Ewwww!)

Birds that forage on the ground are likely to encounter ticks so its no surprise that the Connecticut warbler and this song sparrow acquired them.

(photo from Scott, & Clark, Kerry & Coble, & Ballantyne,. (2019). Detection and Transstadial Passage of Babesia Species and Borrelia burgdorferi Sensu Lato in Ticks Collected from Avian and Mammalian Hosts in Canada. Healthcare. 7. 155. 10.3390/healthcare7040155)

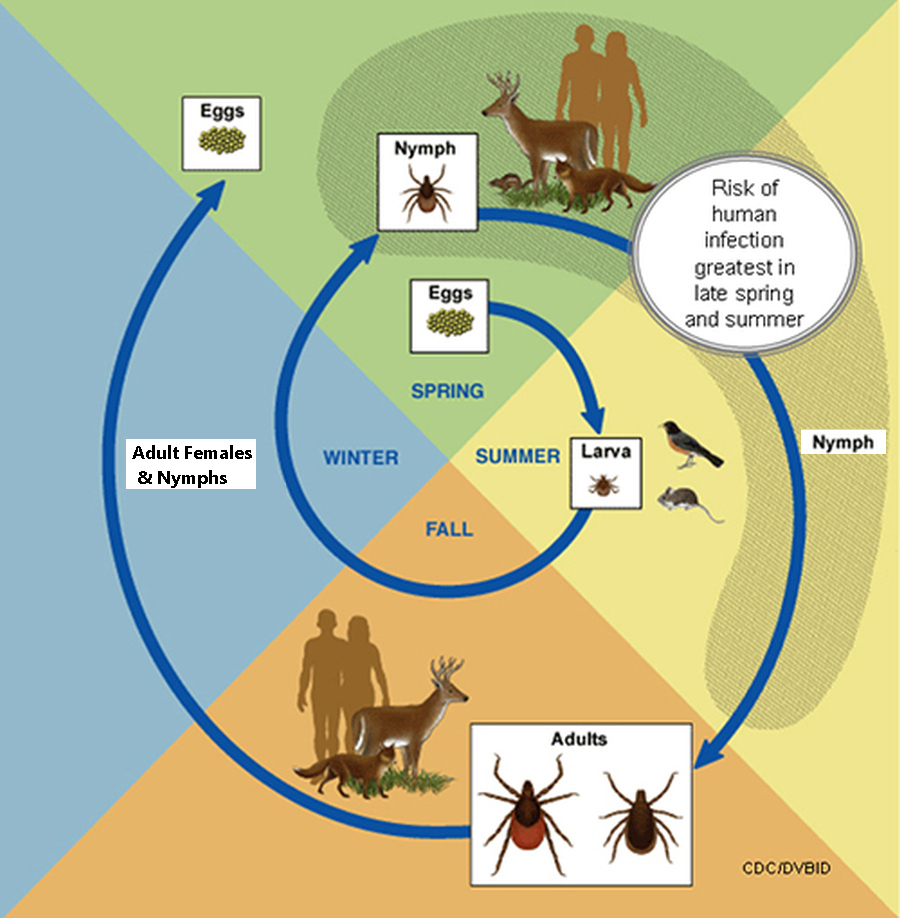

Birds, in fact, are an integral part of the tick’s life cycle. Notice the robin in the Summer section of the CDC diagram below.

I used to say that deer were the black-legged ticks’ long distance transport system but I’ve changed my mind. It’s birds. A 2015 study found that 3.56% of the songbirds migrating north into Texas in the spring are carrying tick(s), most of which are native to Central and South America.

The bird-tick transport system works both ways. A 2019 tick-host-pathogen study in Canada found that some birds carry ticks with pathogens on fall migration.

Poor birds! They need all the strength they can get to complete their migration. It doesn’t help when ticks are sucking their blood.

Meanwhile, be careful about ticks out there! Lyme disease, transmitted by ticks, is terrible. Check your clothing while you’re in the field and thoroughly check your body for ticks when you return home. Click here for ways to prevent infection by keeping ticks off your clothes and body.

p.s. Support Nick Liadis’ efforts with a donation at Bird Lab’s GoFundMe site.