22 October 2010

I thought my blog’s anatomy series was nearly over because I was running out of material. Then last night Chuck Tague presented an excellent program at the Wissahickon Nature Club on how bird anatomy is adapted for flight. Now I’m inspired.

What most impressed me is that birds have the same basic internal equipment that we do — lungs, backbone, arms, toes, etc. — but the location, proportions and shapes of their body parts are altered because they fly.

For instance, human heads can afford to be heavy (and they are!) because we walk upright and easily balance our heads at the top of our bodies. Birds’ heads cannot be heavy unless something equally heavy balances them horizontally at the other end. Their solution is to have lightweight heads and alter the shape of their bodies to change the weight distribution.

Which leads me to the keeled sternum or breastbone. It provides the anchor for the flight muscles. Notice that it’s huge and sticks out! When a bird flies its keel is positioned in the air the same way a boat’s keel is positioned in the water — one of many reasons why the sternum takes this shape.

If humans had keeled breastbones we’d tip over as we walk. Instead our sternum is flat and positioned vertically.

There are a few birds who don’t have keeled breastbones and they are… can you guess?… birds that don’t fly. Ostriches, emus, cassowaries, rheas and kiwis all have flat sternums. A keel would get in their way and possibly throw them off balance as they walk. Their unusual sternum (for a bird) gave their group a name. Ratites means “raft-like sternum.”

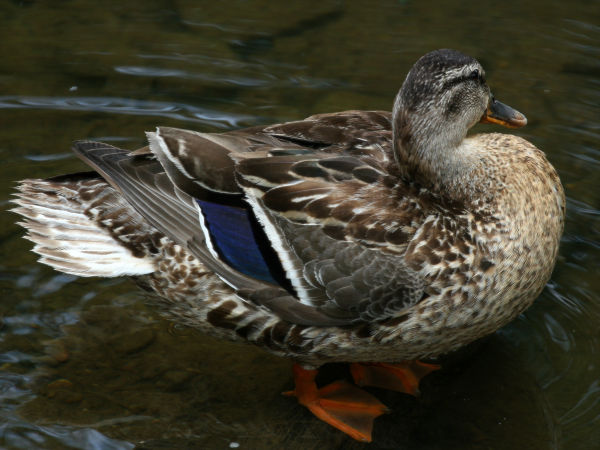

(photo from Wikimedia Commons. Click on the photo to see the original.)

A bird’s chin is exactly where you’d expect it to be — just under its beak — but of course birds’ chins don’t stick out like ours do.

A bird’s chin is exactly where you’d expect it to be — just under its beak — but of course birds’ chins don’t stick out like ours do.