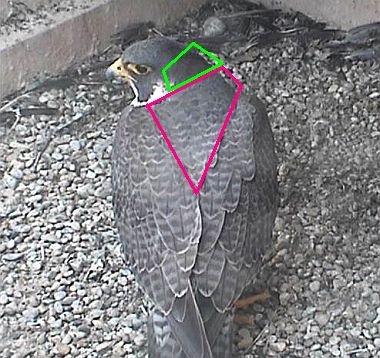

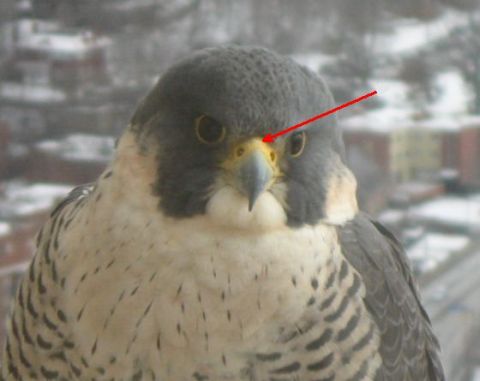

Dorothy has agreed to pose for another anatomy lesson so today I’ll cover two of the features she’s showing in this picture: nape and mantle.

Dorothy has agreed to pose for another anatomy lesson so today I’ll cover two of the features she’s showing in this picture: nape and mantle.

Just as in humans, the nape on a bird is the back of its neck, marked here in green.

Mantle among humans means a cloak or covering. On birds it refers to the feathers on their backs which I’ve outlined here in pink. When a bird is at rest the mantle is often hard to distinguish from its wings if there’s no color contrast.

Mantle is also used as a verb as in, “She mantled over her prey.” In this case it means “to cloak” and describes how the bird uses its wings and body to hide something from those who might steal it. Click here for a good picture of a red-tailed hawk mantling over its prey in Downtown Pittsburgh.

…Now, if you’re new to this blog you may be wondering who Dorothy is. She’s a wild peregrine falcon who nests at the University of Pittsburgh with her mate E2. She received her name in Wisconsin when she was banded in 1999. Sometimes I pretend to know what she’s saying (witness the beginning of this blog) but she keeps her own counsel. I can only guess her meaning.

On the other hand, I see her nearly every day when I walk by the Cathedral of Learning so if you’re anxiously awaiting peregrine nesting season I know you won’t have long to wait. Dorothy and E2 are courting now and on sunny days they zoom around the Cathedral of Leaning in beautiful courtship flights. Sometimes E2 brings her food to prove he’s a good provider and cement their pair bond.

In a few weeks the National Aviary’s peregrine webcams will be running at Pitt and the Gulf Tower so we’ll be able to see the birds at their nests. In the meantime you can watch Dorothy and E2’s occasional visits to the Pitt nest on the Aviary’s snapshot webpage.

Perhaps you’ll see Dorothy pose like this, showing her nape and mantle.

(photo of Dorothy, the adult peregrine falcon at University of Pittsburgh, from the National Aviary webcam in June 2009)

Last week I read a post on

Last week I read a post on  After last week’s foray into the subject of coverts I’m happy to shift gears and talk about peregrines again.

After last week’s foray into the subject of coverts I’m happy to shift gears and talk about peregrines again.

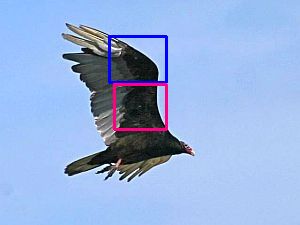

I came across the term “patagial mark” at the Allegheny Front Hawk Watch in November when I was having trouble identifying a passing red-tailed hawk.

I came across the term “patagial mark” at the Allegheny Front Hawk Watch in November when I was having trouble identifying a passing red-tailed hawk.

If you’ve been birding for a while you’ve probably heard, even used, the word “primaries” but the word remiges could be new to you. It was to me.

If you’ve been birding for a while you’ve probably heard, even used, the word “primaries” but the word remiges could be new to you. It was to me.