22 August 2017

How do birds cope with heat? Like us they stand in the shade and bathe to cool off. They also pant, called gular fluttering, and press hot air out of their feathers. But some have a hidden cooling method inside their beaks called nasal conchae (pronounced KONK eye).

Nasal conchae are complex structures that moderate the temperature of inhaled air and reclaim water from exhaled air. A study published in The Auk: Ornithological Advances in 2016 found that birds who live in hot dry places benefit from bigger, better conchae.

Raymond Danner of UNC Wilmington and his colleagues used CT scans to display the internal beak structures of two subspecies of song sparrows. The specimens were collected in Delaware and Washington, DC.

Delaware and D.C. don’t seem to have different climates, but a bird of the dunes copes with a hot dry micro-climate compared to one that nests in a wooded inland park.

Indeed, as reported in Science Daily, the CT scans showed that “the conchae of the dune-dwelling sparrows had a larger surface area and were situated farther out in the bill than those of their inland relatives.”

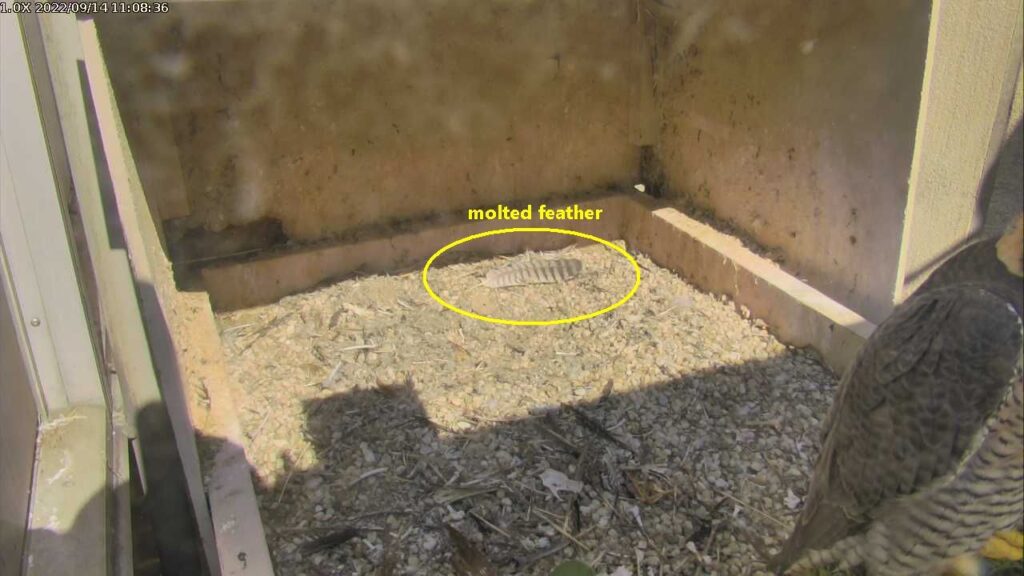

Here’s a dune-dwelling song sparrow beak with elaborate air conditioning structures.

This extra internal gear means the dune-based song sparrows (Melospiza melodia atlantica) have larger beaks than their inland cousins.

I have not noticed slightly larger beaks on song sparrows at the beach. Have you?

(photo by Peter Bell)