25 February 2025

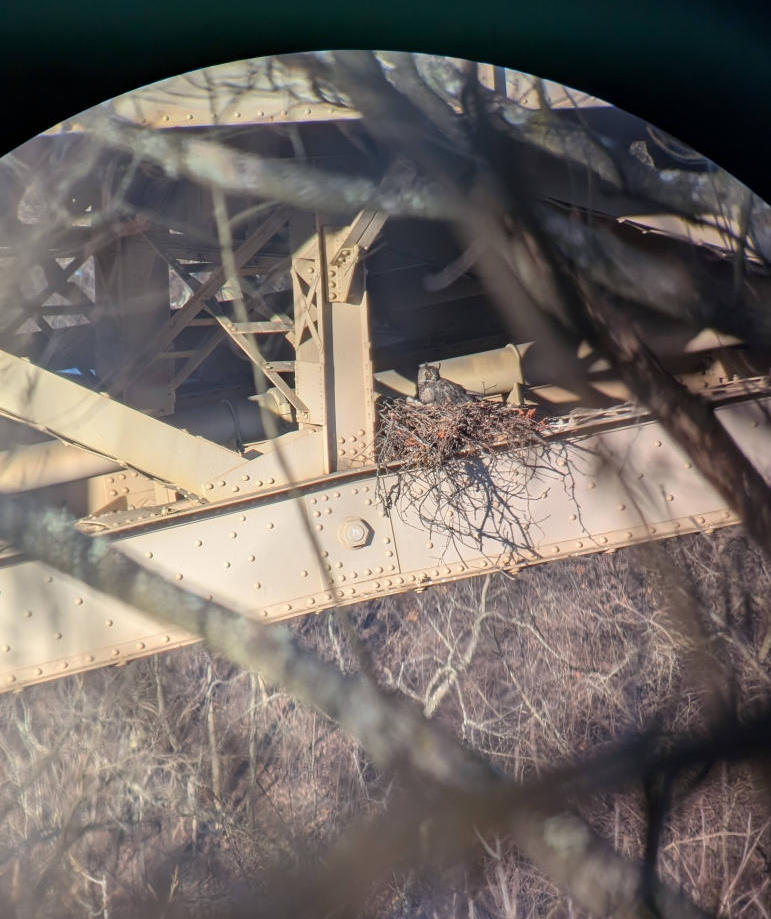

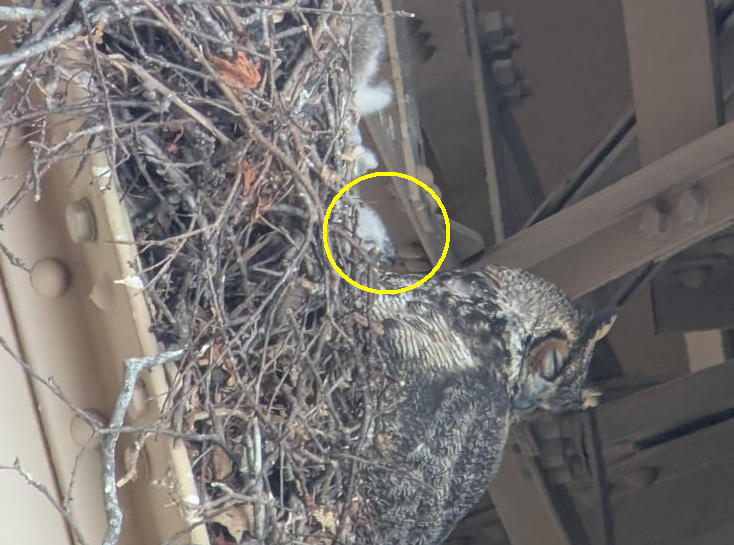

After a month of excitement over Schenley Park’s great horned owls nest, I’m switching gears this week to find the owls I missed in Minnesota eleven years ago.

Back in 2014 I attended the Sax-Zim Bog birding festival during one of the coldest winters of the century. I had a wonderful time full of new experiences and Life Birds but I never saw my target bird, the great gray owl, so I’m going back this week with Frank Nicoletti as my guide to find one.

From the top of their heads to the tip of their tails great gray owls (Strix nebulosa) are the world’s largest owl by length with a wingspan up to 5 feet long.

Although it appears to be more massive than other owls of the northern forest, its actual body mass is at least 15% smaller than the more common Great Horned Owl (Bubo virginianus), with which it shares habitat. Thus its plumage makes up much of the bulk of the bird, allowing it to withstand the bitter cold of northern winters.

— Birds of the World: Great Gray Owl — emphasis added

This cross section of a taxidermied model at the Zoological Museum in Copenhagen shows how small the bird’s body really is.

To give you an idea of their size, here’s a video from the Owl Research Institute of banding an adult male great gray owl and his chicks in (probably) northern Montana in 2020. Note that the male is smaller than his mate.

Perhaps I’ll only see one from a distance but you can tell by its shape that this is a great gray!

p.s. I checked my Life List again and discovered I’ve never seen a boreal owl (Aegolius funereus). Fingers crossed for both.