9 June 2023

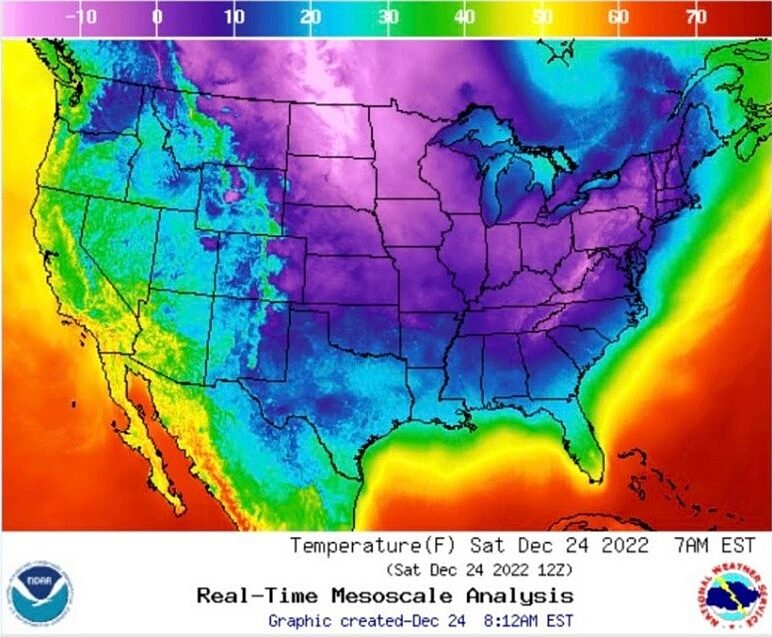

Plants are drooping, water levels are low, and clouds of dust engulf dirt roads in western Pennsylvania. It hasn’t rained for almost three weeks at a time of year that’s usually wet. Yesterday it became official. We’re in a drought.

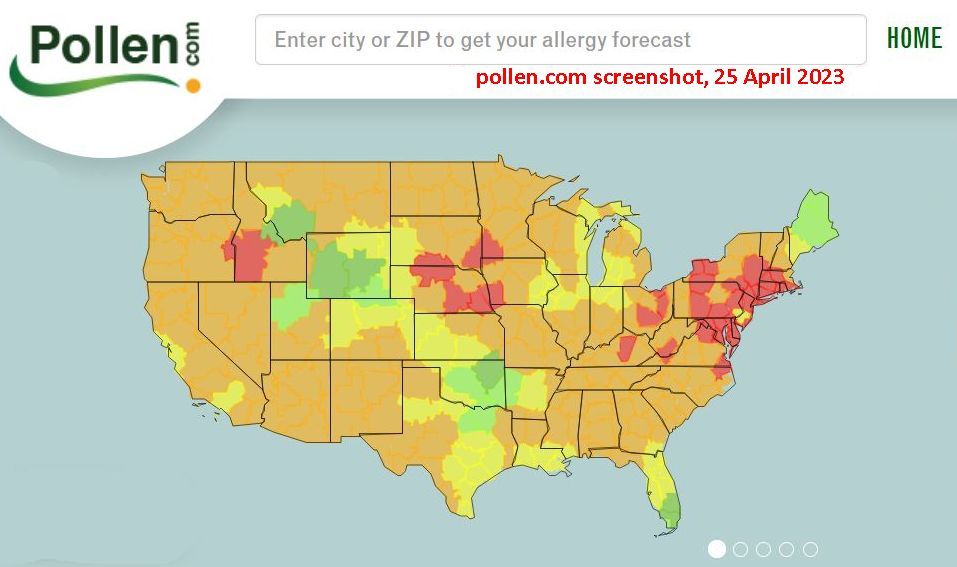

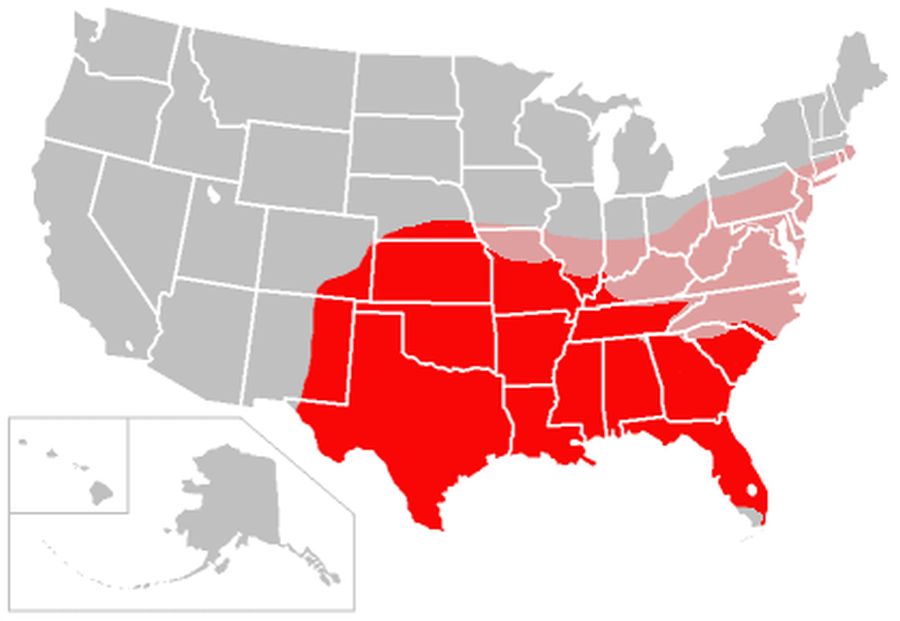

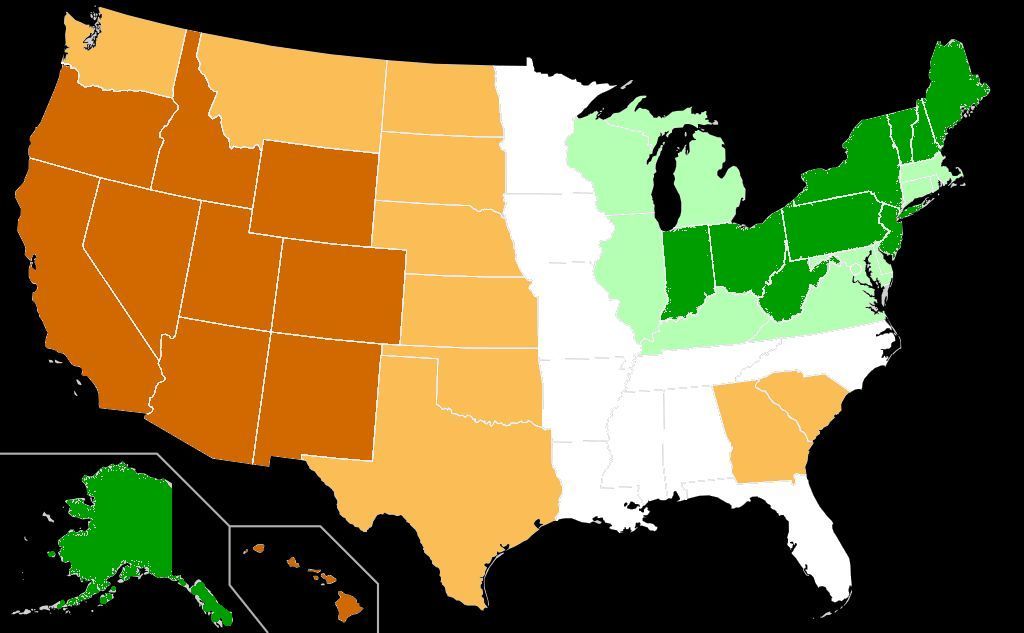

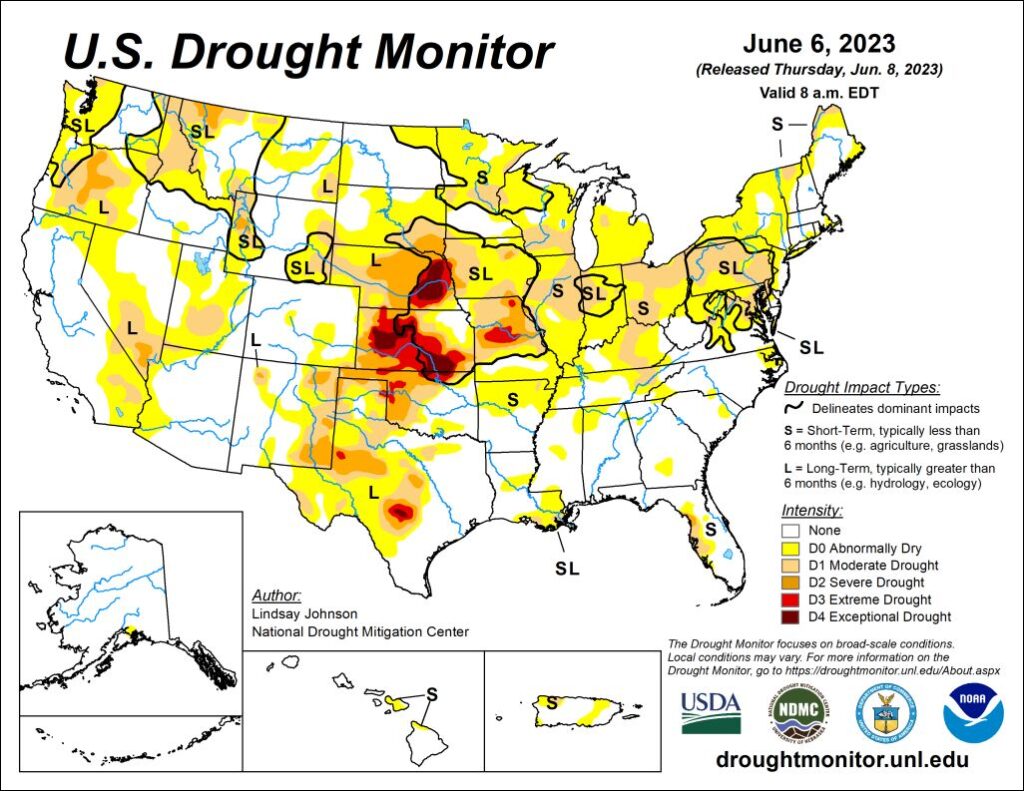

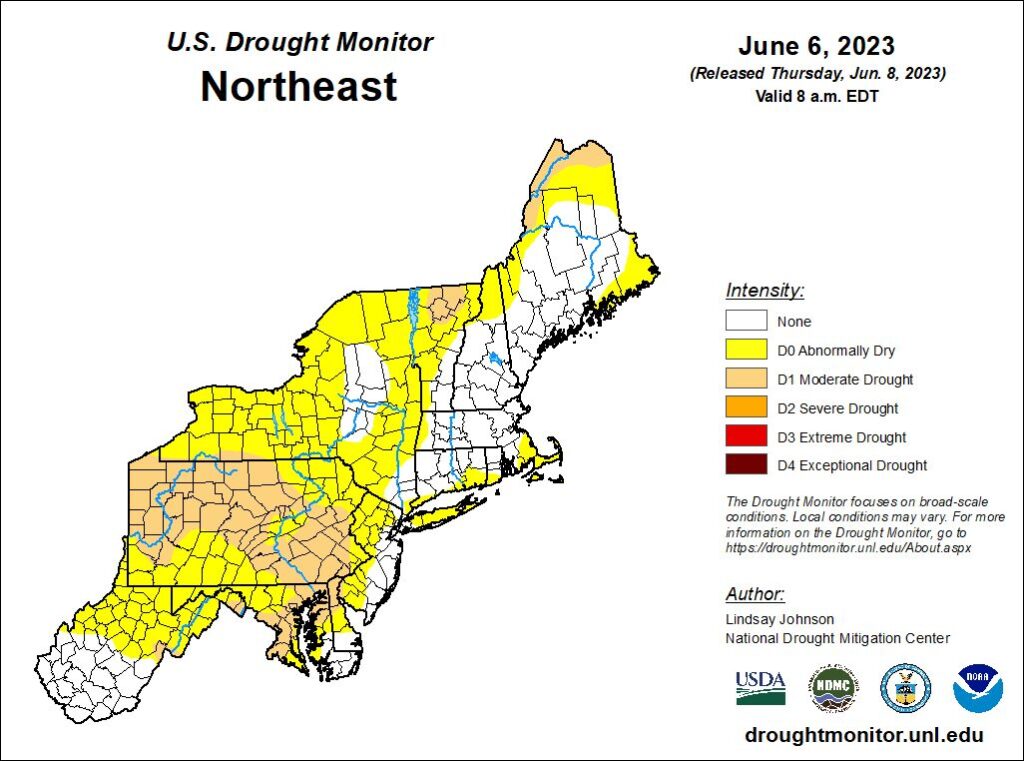

Every week the U.S. Drought Monitor at University of Nebraska-Lincoln issues a nationwide drought assessment. Pennsylvania is labeled “SL” on this week’s map for evidence in both Short term and Long term indicators. (Click here for the latest Drought Map.)

Most of Pennsylvania, including Allegheny County, is in Moderate Drought.

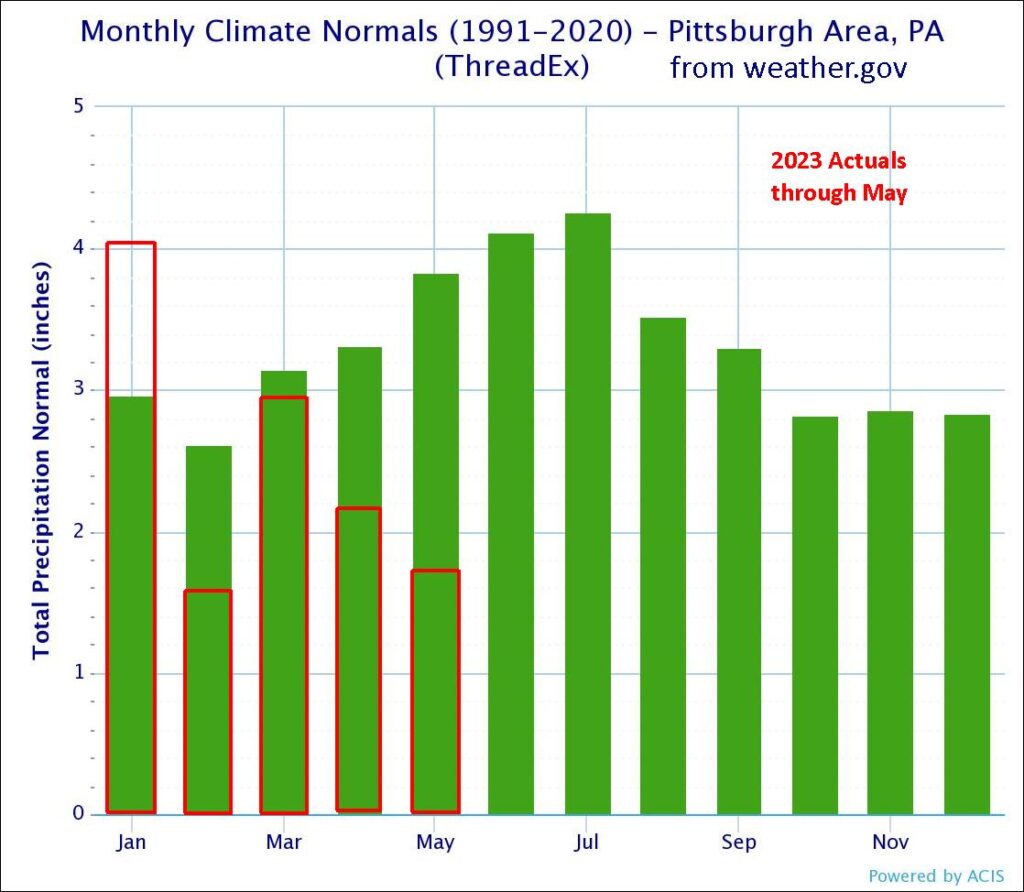

The drought seems sudden but it’s been building for a while. Precipitation was above normal last year through January 2023 but starting in February it fell off. April and May were seriously below normal. June has been bone dry so far. As of today Pittsburgh has a year-to-date precipitation deficit of 4.55 inches.

Even the hardiest invasive plants are wilting in the city parks …

… small tributaries are completely dry …

… and the cascade pools in Schenley Parks’ Phipps Run are stagnant. Unfortunately stagnant water is a breeding ground for mosquitos, an unexpected consequence of drought.

The forecast calls for rain on Monday 12 June, but one day’s rain can’t overcome the 4.5+ inch deficit.

Hoping for more rain soon. Meanwhile check out these drought tips for lawns and camping at TribLive: Dry conditions expected to continue in Western Pennsylvania.

(photos by Kate St. John, maps from U.S. Drought Monitor)