5 January 2022

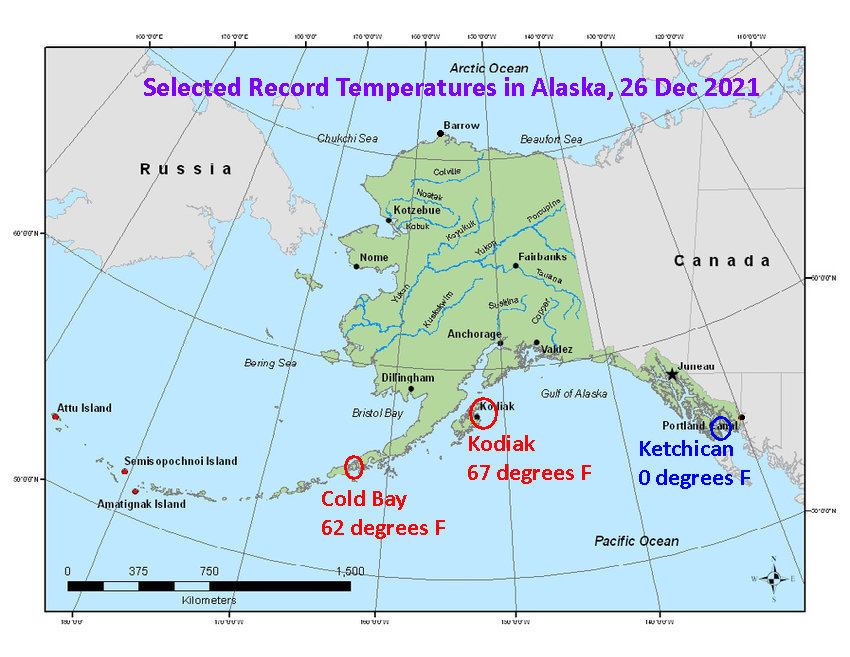

On 26 December 2021 the record high temperature for Alaska — for the entire state — was set at Kodiak Island when it reached 67oF at a tidal gauge. This was so unusual that the National Weather Service triple checked to make sure. Kodiak Airport was 65 degrees, Cold Bay was 62.

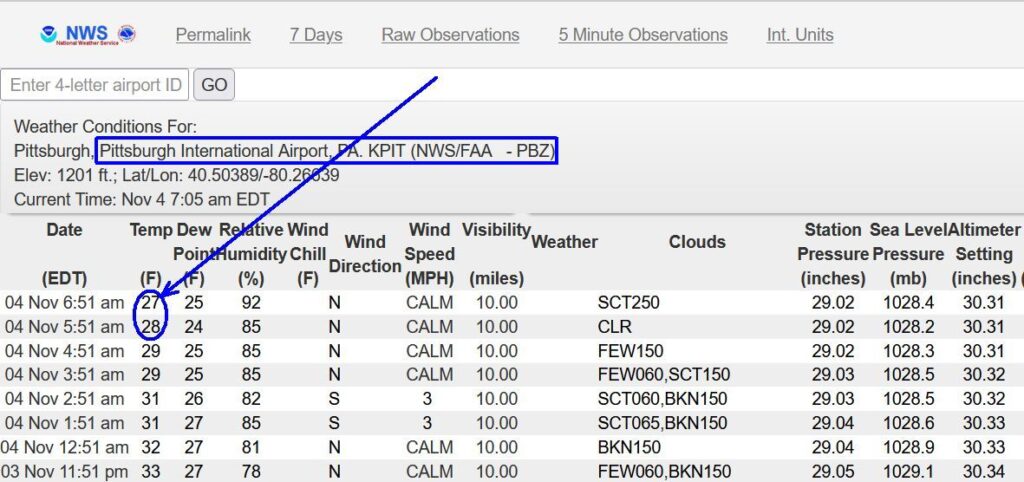

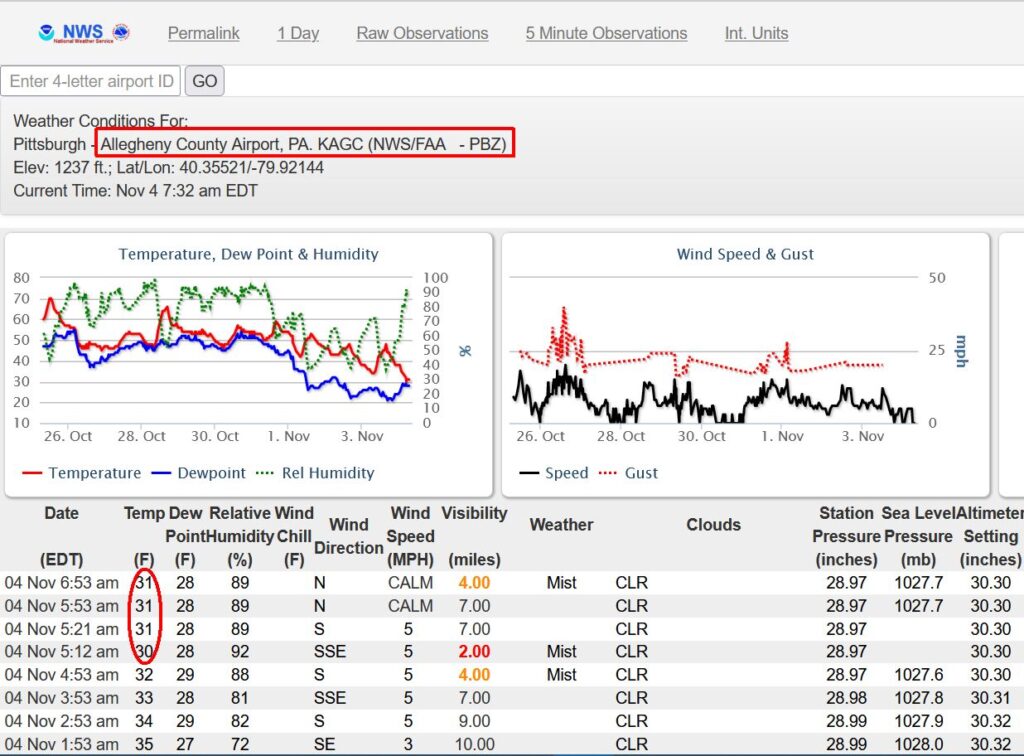

Pittsburgh also had record heat in December 2021 but not as hot as Alaska. Our record-tying high was 64oF on 16 December.

?The Kodiak Tide Gauge station recorded an amazing 67°F yesterday. This is a new statewide temperature record for December. The Kodiak Airport recorded 65°F. This broke their monthly record by 9°F! The weather balloon launched at the same time confirms these amazing readings. pic.twitter.com/IuTPCGOrFU

— NWS Alaska Region (@NWSAlaska) December 27, 2021

Other hi temp records were set y’day across the Bering. Cold Bay obliterated its daily record by 18º, also setting a monthly record for Dec. It is the warmest temp recorded between Oct. 27 and May 7, so monthly records would’ve been set in Nov, Jan, Feb, Mar, and Apr.#AKwx pic.twitter.com/umQXivoGgP

— NWS Anchorage (@NWSAnchorage) December 27, 2021

Meanwhile, across the Gulf of Alaska from the record heat was a record low temperature of 0 degrees F at Ketchican.

Ketchikan did it again yesterday, by breaking it’s record low temp of 5F from 1917! when it recorded 0. Other locations also broke their daily low temp yesterday Juneau forecast office (-7F), Haine#2(-2f), Klawock airport (3F), Pelican(10F) & Thorne Bay (0F) #akwx .@KRBDRadio pic.twitter.com/cruI3QeUe5

— NWS Juneau (@NWSJuneau) December 27, 2021

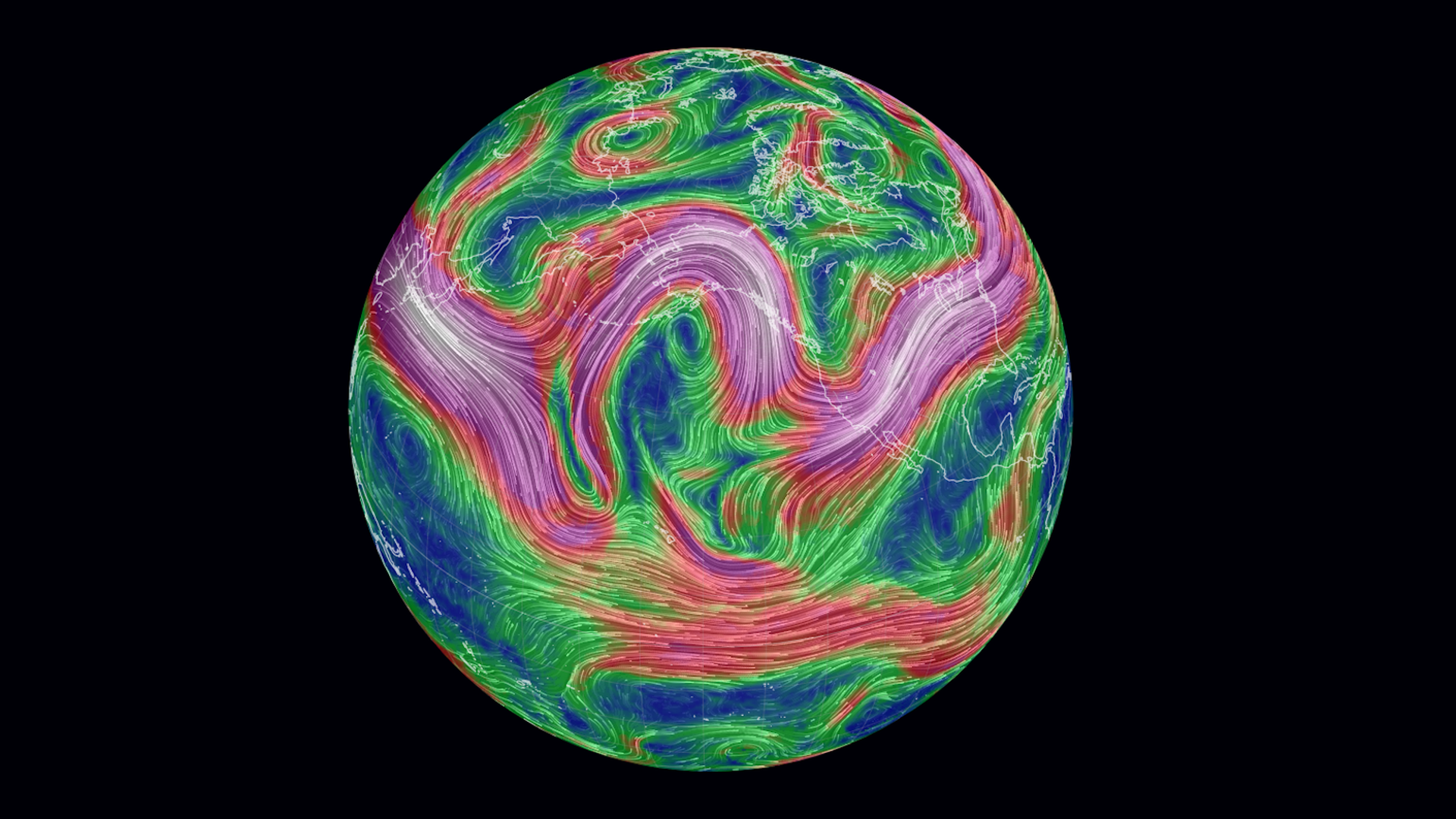

How could Alaska have such high and low extremes on the same day? The wildly wobbling jet stream pushed warm air up the western side of the Gulf of Alaska and poured cold air down its eastern side. This jet stream map, centered on the Gulf of Alaska, is explained at Axios: Alaska sets December temperature record at 67 degrees.

The extremes caused trouble throughout Alaska as unusual rain turned to ice and heavy snow. Alaska is definitely the poster child for climate change.

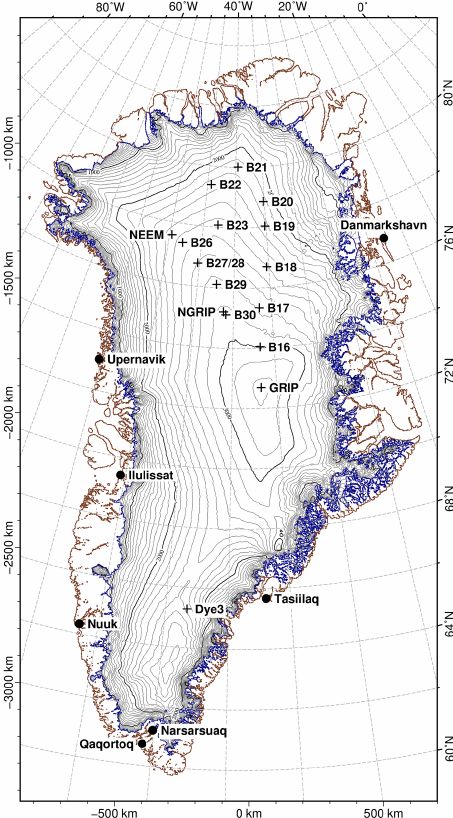

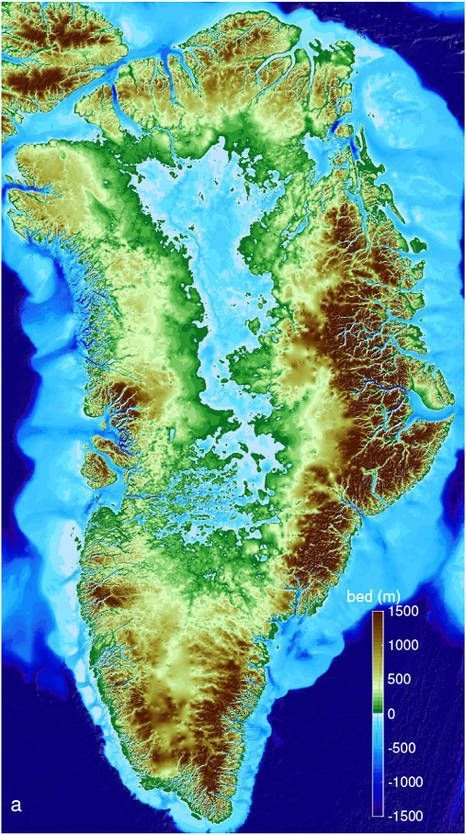

(map from data source: Alaska Geospatial Data Clearinghouse via Researchgate, tweets from @NWSAlaska, jet stream winds from earth.nullschool.net embedded from Axios)