20 July 2021

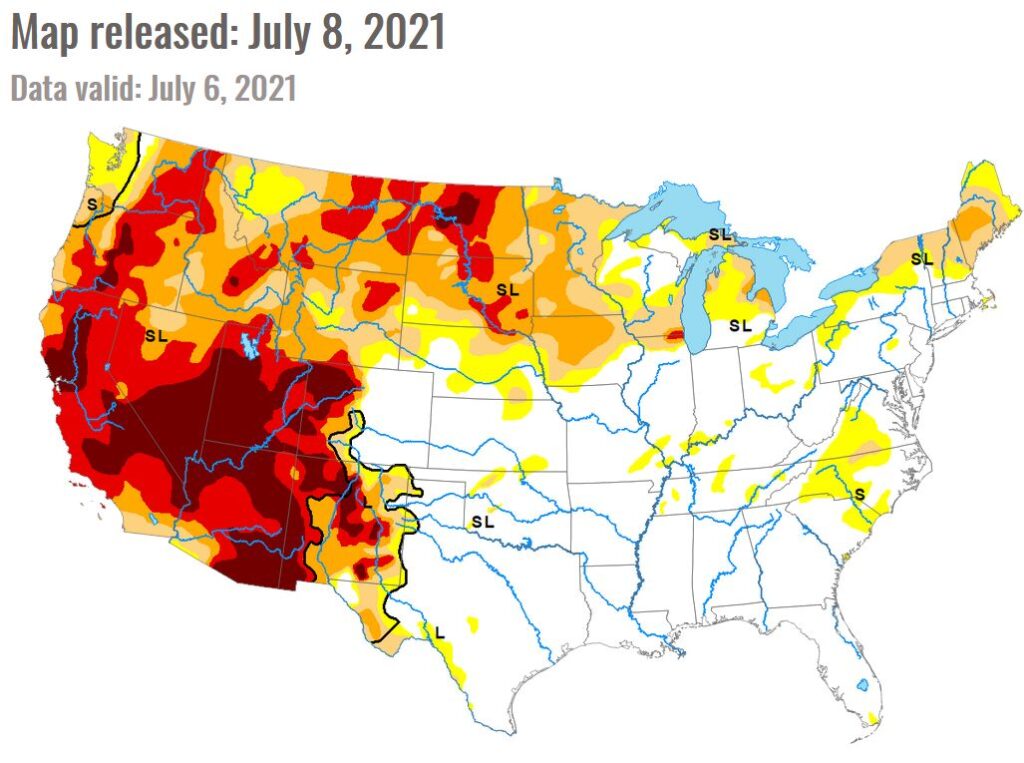

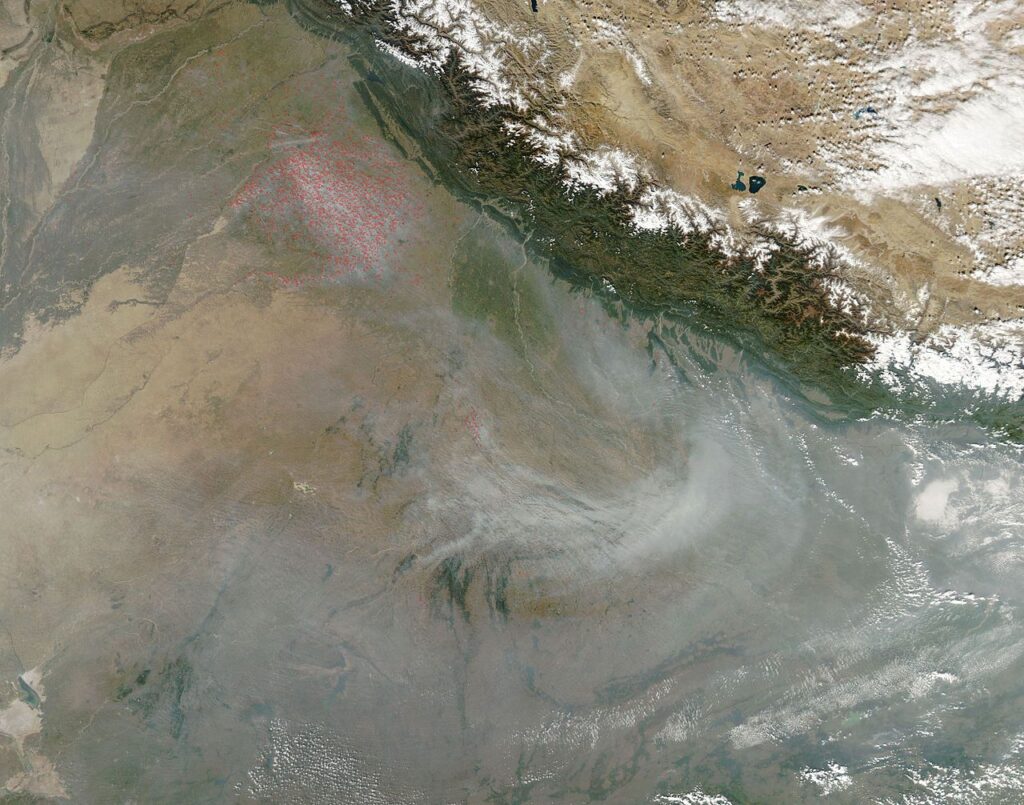

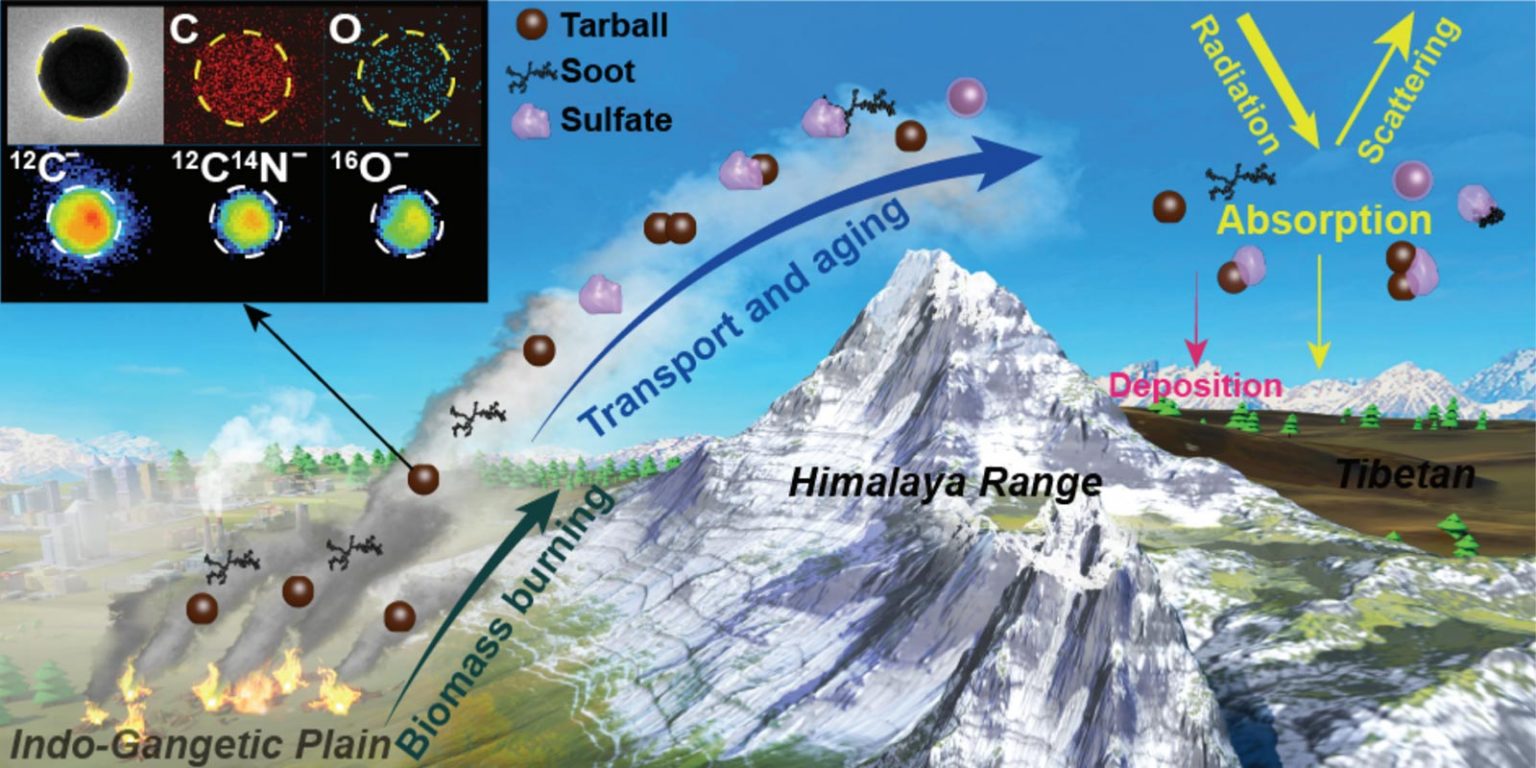

Withering heat, parching drought, devastating floods, dangerous wildfires.

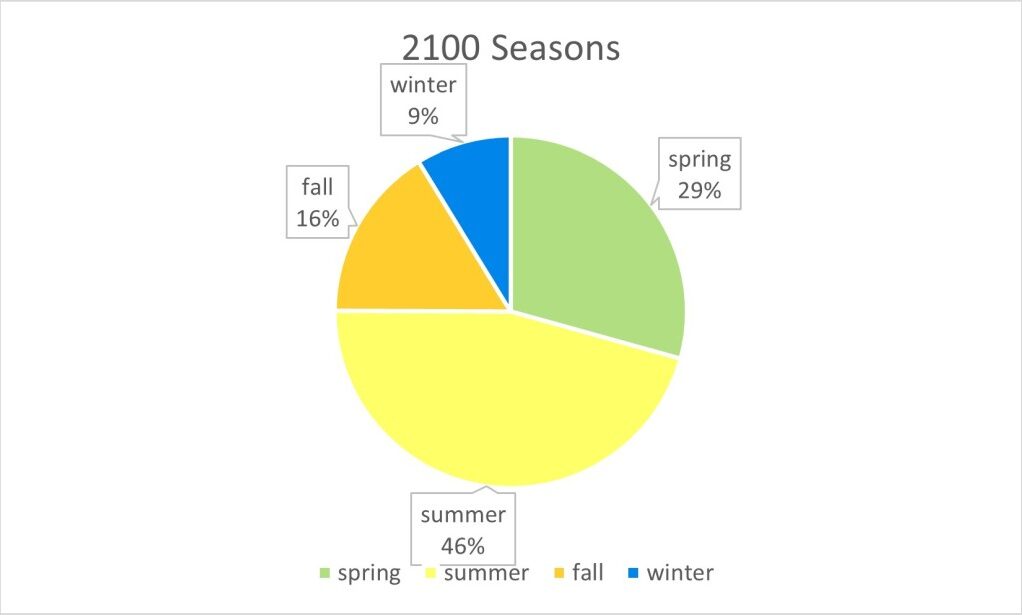

As unpleasant as this summer has been in the Northern Hemisphere we comfort ourselves that better weather will arrive with autumn in September. But even that is changing. A new study published in Geophysical Research Letters predicts that by the end of this century winter, spring and fall will retreat while summer will last nearly half the year.

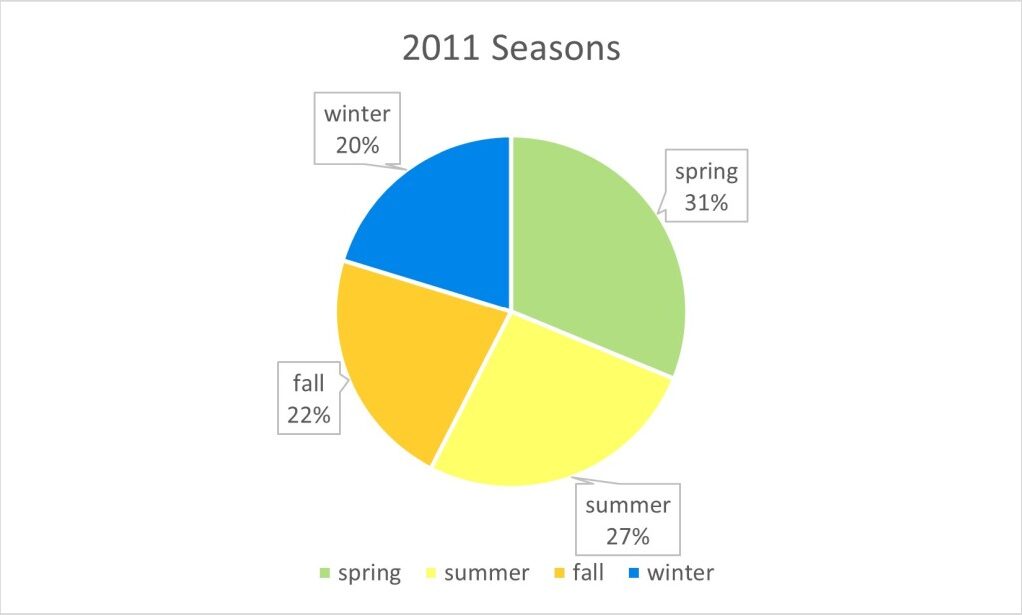

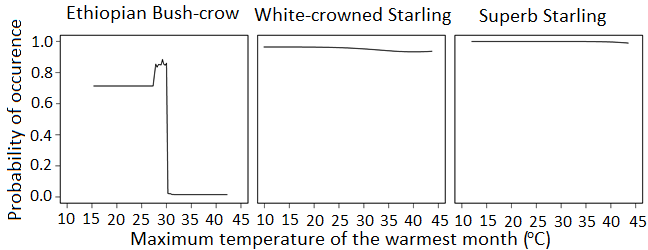

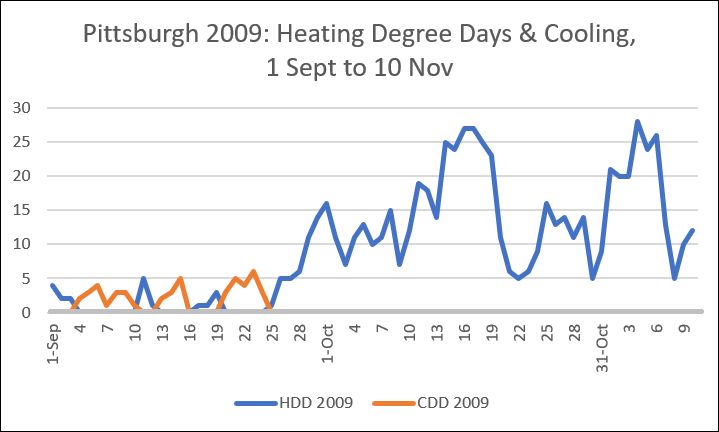

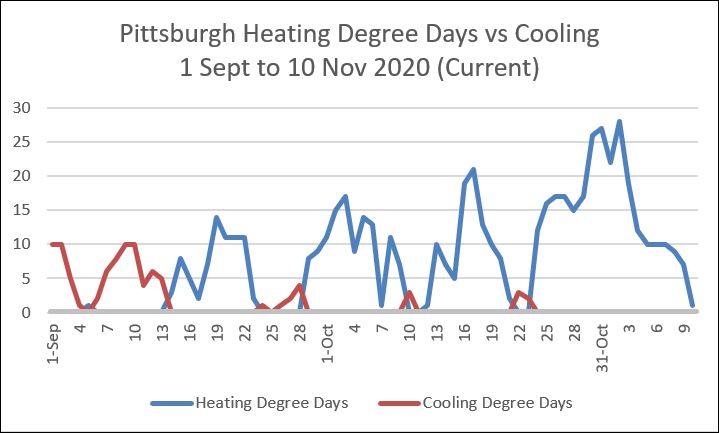

For perspective on the future the researchers studied the past across the Northern Hemisphere, specifically the length of seasons from 1952 to 2011. They set the parameters for summer as the “onset of temperatures in the hottest 25% during that time period, while winter began with temperatures in the coldest 25%.” Spring and fall filled the gaps.

During those sixty years, summers got longer while the other seasons shrank. The slides below show the historical seasons 1952 and 2011 plus the study’s prediction for the year 2100. By then summer will run from May to October.

Average seasonal lengths in Northern Hemisphere, information from Phys.org

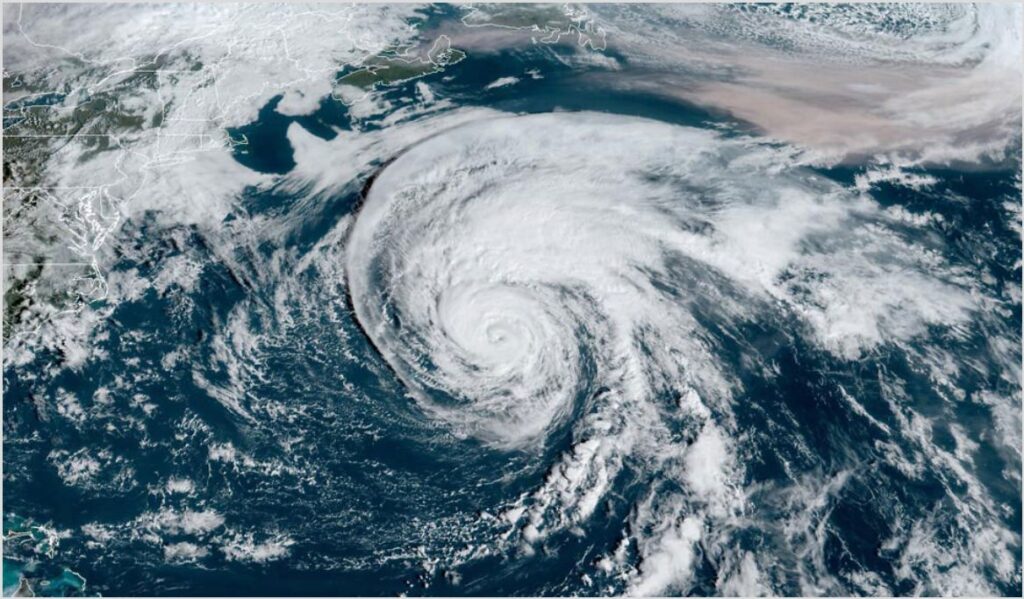

For those of you who don’t like winter this sounds like a great idea but the reality will be unsettling. The long summers and short winters will continue to have extreme temperature and precipitation swings with stunning storms like those we’ve seen in recent years. Imagine the heat of July lasting three months or more.

Meanwhile pleasant days will become scarce. My favorite seasons, spring and fall, will be shorter.

Our great-grandchildren will live in a very different world.

Read more and see the large version of this animation at Northern hemisphere summers may last nearly half the year by 2100 at Phys.org.

(photo from Wikimedia Commons, simple pie charts by Kate St. John, embedded animation from Phys.org)