4 February 2024

Any day with a crow in it is full of promise.

— Crows: Encounters with the Wise Guys, by Candace Savage

Crows are a favorite theme of mine so I was pleased that we encountered Africa’s most common crow at nearly every birding site on our trip in southern Africa. We saw only one Corvus species, the pied crow (Corvus albus). He wears a white vest.

Pied crows are intermediate in size between crows and ravens and are closely enough related to Africa’s dwarf raven, the Somali crow, that they can hybridize. However their behavior is closer to that of American crows (Corvus brachyrhynchos).

Wikipedia says the same of both of them.

The pied crow‘s behavior is more typical of the Eurasian carrion crow.

American crows are the New World counterpart to the carrion crow and the hooded crow of Eurasia. They all occupy the same ecological niche.

Both are smart and inquisitive.

The pied crow’s voice is intermediate between crow and raven.

Typically we saw only one or two crows at a time except at dawn when they left their roost. Then my highest count was eight.

The main difference between pied and American crows appears to be that pied crows don’t migrate and are less gregarious. As far as I know they never aggregate into huge flocks.

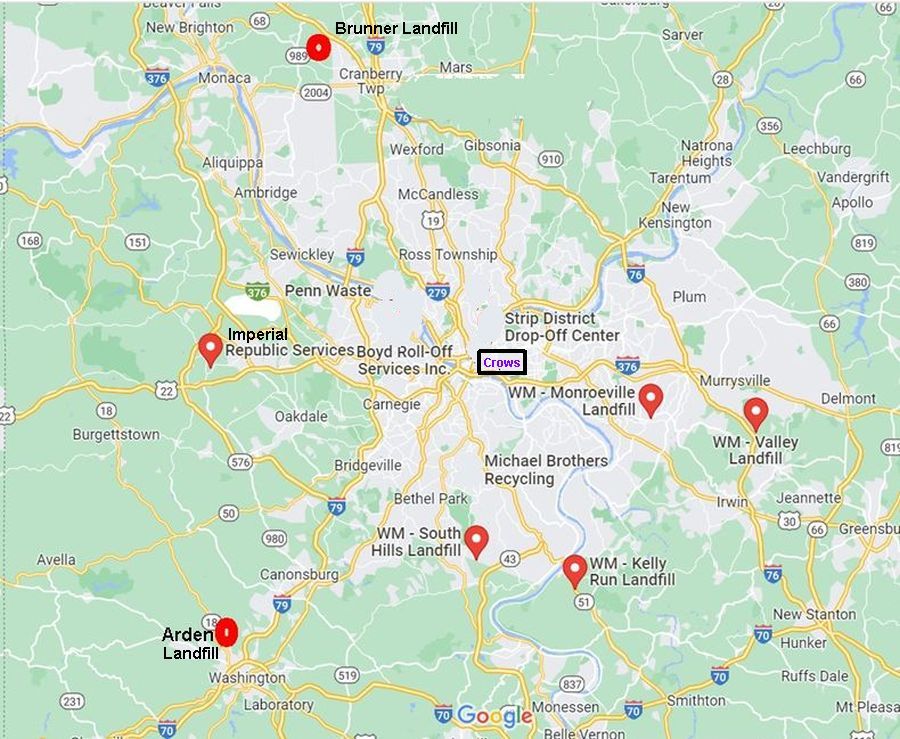

Africans would be surprised, and perhaps horrified, to see Pittsburgh’s flock of 20,000 American crows in winter.

(photos from Wikimedia Commons)