7 October 2023

The best photos from this week have been published already (Yesterday at Hays Woods Bird Banding) so I’m reaching back to late September for a few of things I’ve seen.

Bees of all kinds are attracted to deep purple asters beside the Westinghouse Memorial pond in Schenley Park. The honeybee, above, is hard to see near the flower’s orange center.

At Duck Hollow, yellow jewelweed still has flowers as well as fat seed pods. Try to pull one of the pods from the stem and see what happens.

On 28 September I explored the slag heap flats near Swisshelm Park where (I think) solar arrays will be installed. Because the slag is porous the flats are a dry grass/scrub land where this shrub would have done well except that it’s been over-browsed by too many deer. It looks like bonsai.

Deer overpopulation is also evident by the browse line at the edge of the flats.

On 26 September at Duck Hollow I encountered an optical illusion where Nine Mile Run empties into the Monongahela River. It looks as if this downed, waterlogged tree is damming the creek and that the water is lower on the downriver side of it. This illusion seems to be caused by the smooth water surface on one side of the log.

We found a tiny red centipede crossing the trail at Frick Park on 30 September …

… and a puffball mushroom outside the Dog Park.

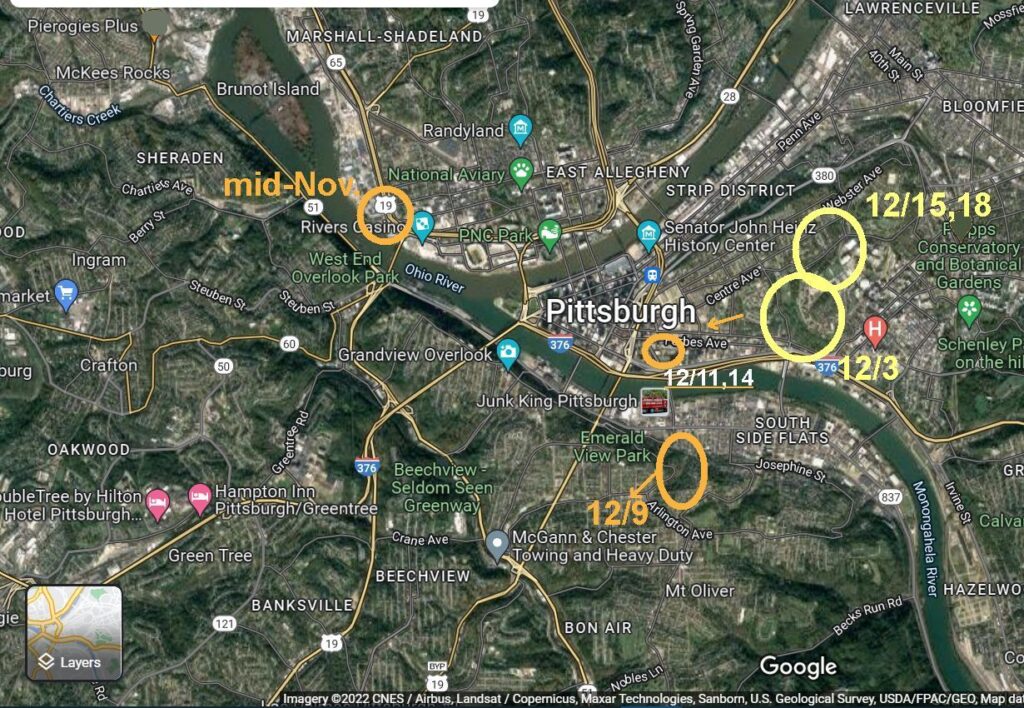

On 27 September hundreds, if not thousands, of crows gathered at dusk near Neville Street in Shadyside before flying to the roost. I thought this would happen again the next day but they changed their plan and have not come this close again.

Sometimes sunrise is the most beautiful part of the day.

These photos don’t give the impression that it’s been abnormally dry, but precipitation in Pittsburgh is down 6″ for the year. Almost 2″ of that deficit occurred in September. The Fall Color Prediction says our leaf color-change is later than usual.

(photos by Kate St. John)