11 February 2025

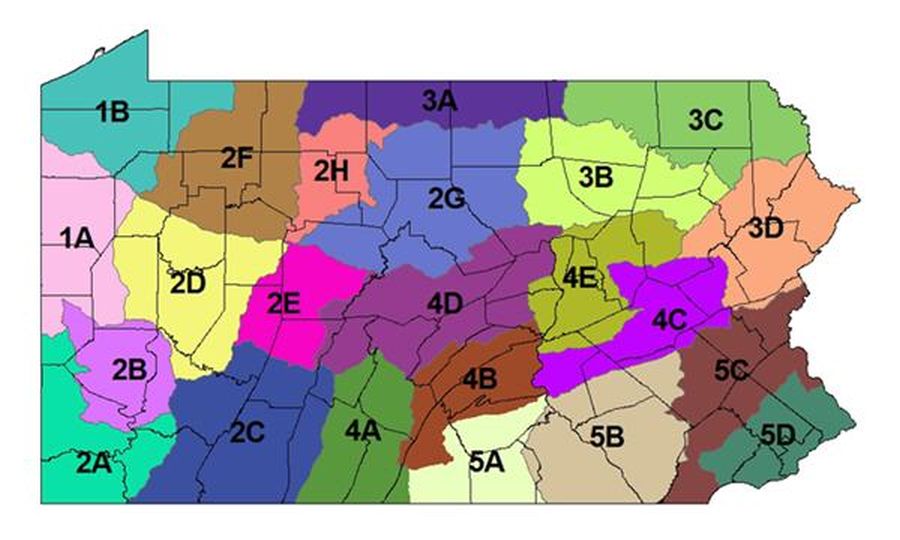

It’s been six weeks since hundreds of snow geese stricken with highly pathogenic (HPAI, H5N1) avian influenza were found dead and dying in Pennsylvania’s Lehigh and Northampton Counties on New Year’s Day.

By 24 January bird flu had killed 5,000 snow geese in Northampton County as well as raptors and scavengers including bald eagles and vultures and a snowy owl at Presque Isle.

Meanwhile the virus jumped from wild birds to an enormous commercial poultry farm: The first commercial poultry outbreak in PA since Feb 2024 was reported in Lehigh County on 27 January in a 50,000 commercial layer flock (egg farm). All commercial poultry facilities within a 10km (6.2 mile) radius have been placed under quarantine. (This is an example of why eggs are scarce and expensive.)

And so it comes as no surprise that the #1 location for snow goose migration in Pennsylvania — Middle Creek Wildlife Management Area near Kleinfeltersville — has been closed for the spring migration season.

The PA Game Commission announced ACCESS RESTRICTED AT MIDDLE CREEK on 3 February 2025.

HARRISBURG — Due to highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) that is currently affecting many parts of the state, the Pennsylvania Game Commission is restricting public access at the Middle Creek Wildlife Management Area, effective Tuesday.

With the continued warming trends and the anticipated arrival of snow geese to Middle Creek, this decision was made out of an abundance of caution for human and domestic animal health.

Beginning Tuesday 4 February 2025, the following areas will be CLOSED to all public access:

- Willow Point Parking Lot and Trail

- Archery Range

- Boat Launch

- White Oak Picnic Area

- All shoreline access of the lake, INCLUDING fishing

The Wildlife Drive remains seasonally closed, and an extended closure is possible.

Hiking trails (with the exception of Willow Point Trail and Deer Path Trail) and the Visitor Center will remain open during regular business hours, and all events will take place as scheduled.

All visitors are reminded:

- If you have pet birds, backyard domestic poultry, or connections with commercial poultry facilities, you are STRONGLY discouraged to visit during this time to minimize transmission risk.

- You are HIGHLY ADVISED to remain in your vehicles while observing wildlife from roadways.

Please remember the public plays a critical role in wildlife health surveillance. Report sick or dead wild birds to the Game Commission by calling 1-833-PGC-WILD (1-833-742-9453).

— PGC Press Release, 3 Feb 2025

Flocks at Middle Creek can contain 100,000 snow geese and 10,000 tundra swans at the peak of migration. This is what it looked like 3 years ago in 2022. It’s easy to see how these birds could spread contagious diseases.

While bird flu (HPAI) spreads during spring migration remember to:

- Always observe wildlife from a safe distance.

- Avoid contacting surfaces that may be contaminated with feces from wild or domestic birds.

- Do not handle wildlife unless you are hunting, trapping, or otherwise authorized to do so.

UPDATE, 28 Feb 2025 via Post-Gazette: The snow goose death toll in Lehigh County, Pennsylvania is now at 5,000 –> and these are just the birds that people could see and count.