11 March 2025

A new study published last week in the journal Science analyzed butterfly surveys from 2000 to 2020 to determine the population status of each species in the continental U.S. The results were sobering.

Total butterfly abundance (all individuals of all species) decreased across the contiguous US at a rate of 1.3% annually, for a cumulative 22% decline in overall abundance between 2000 and 2020.

— Science: Rapid butterfly declines across the United States

during the 21st century

The only region of the continental US that didn’t suffer was the Pacific Northwest where the total population remained stable and the highly irruptive California tortoiseshell (Nymphalis californica) surged on and off as expected.

The study found that declines were common and increases rare.

Over our two-decade study period, 33% of individual butterfly species (114 of 342) showed significantly declining trends in abundance. Conversely, only 3% of species increased.

— Science: Rapid butterfly declines across the United States

during the 21st century

For instance, the West Virginia white (Pieris virginiensis), above, declined each year by nearly 20%, in part because they are fooled into laying eggs on invasive garlic mustard that kills their caterpillars. By now 98% of them are gone.

And in southern Texas and south Florida the Soldier butterfly (Danaus erisemus), a relative of the monarch, declined about 15% per year, which means about 96% of them gone.

Learn more about the study and see the graphs of declining species in Science.

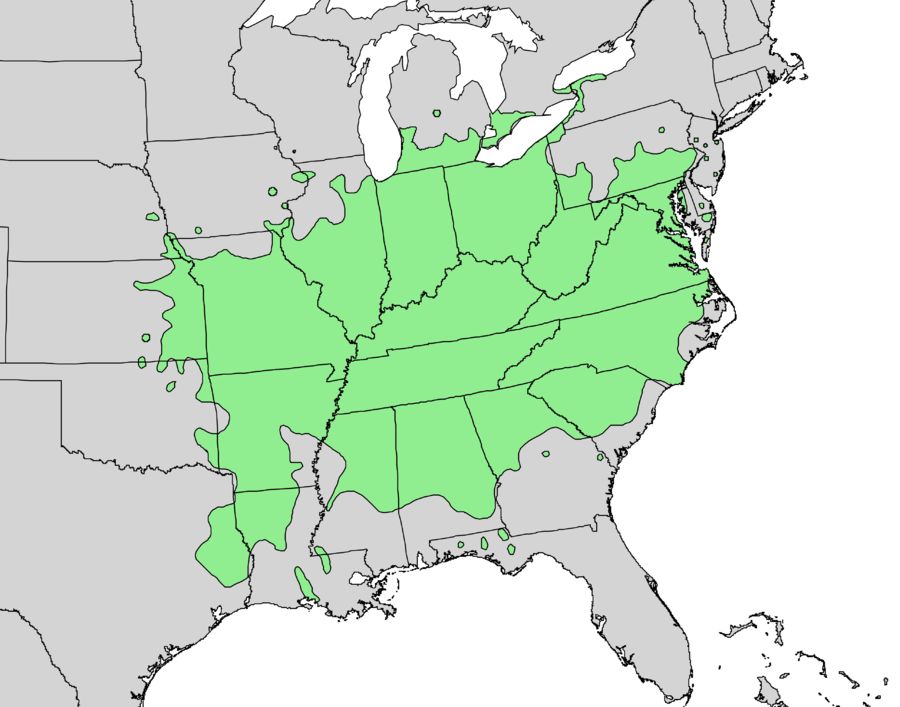

Meanwhile, what can we do to save butterflies? In some cases it simply means planting the butterfly’s host plant. The zebra swallowtail returned to Pittsburgh after an absence of 87 years(!) because many people planted its host plant, the pawpaw tree.