6 May 2021

Now that the trees have leafed out and bug season is firing up in Pennsylvania, it’s time to watch for and report the spotted lanternfly.

Spotted lanternflies (Lycorma delicatula) are invasive planthoppers native to China and Vietnam whose favorite food is the invasive Ailanthus, the Tree-of-Heaven. If they ate only Ailanthus it would be OK but their sharp mouth parts pierce the stems and suck the sap of grapevines, hops, apple trees, peaches and hardwoods including oaks and cherries. They’re bad news for agriculture and forests.

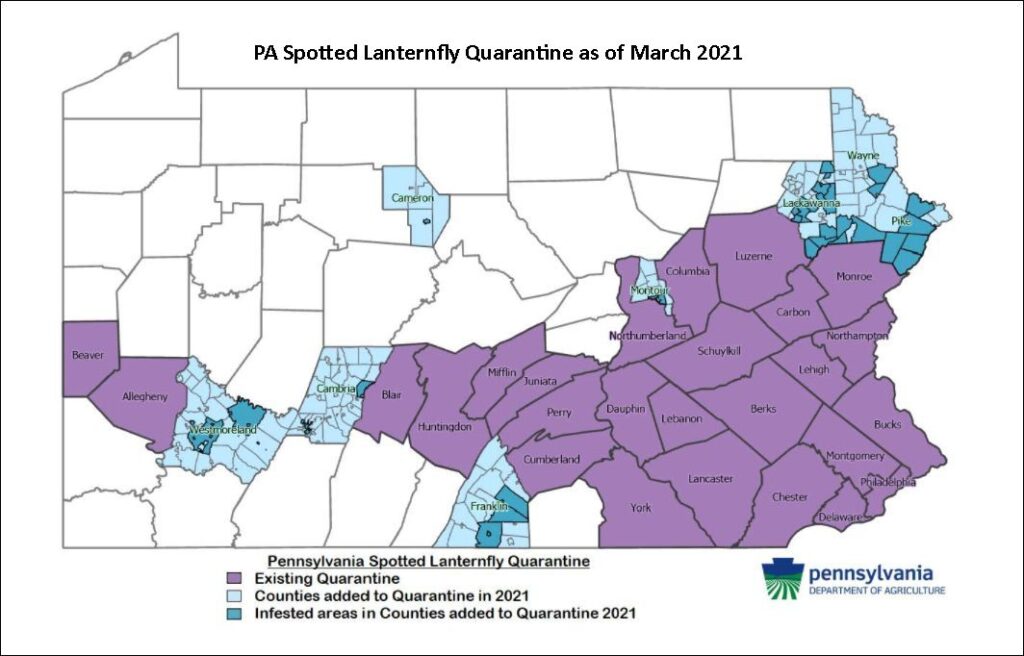

Lanternflies are making quick progress across Pennsylvania because they’re aided by human transportation. First discovered in North America in Berks County, PA in 2018 the bug spread through eastern PA for two years. In early 2020 it was found on rail cars at the Norfolk Southern railyard in Conway, Beaver County. Soon after in Allegheny County. Early this year it completed an unbroken path through the lower third of the state by adding Westmoreland and Cambria Counties. What’s on this path? The Norfolk-Southern Railroad.

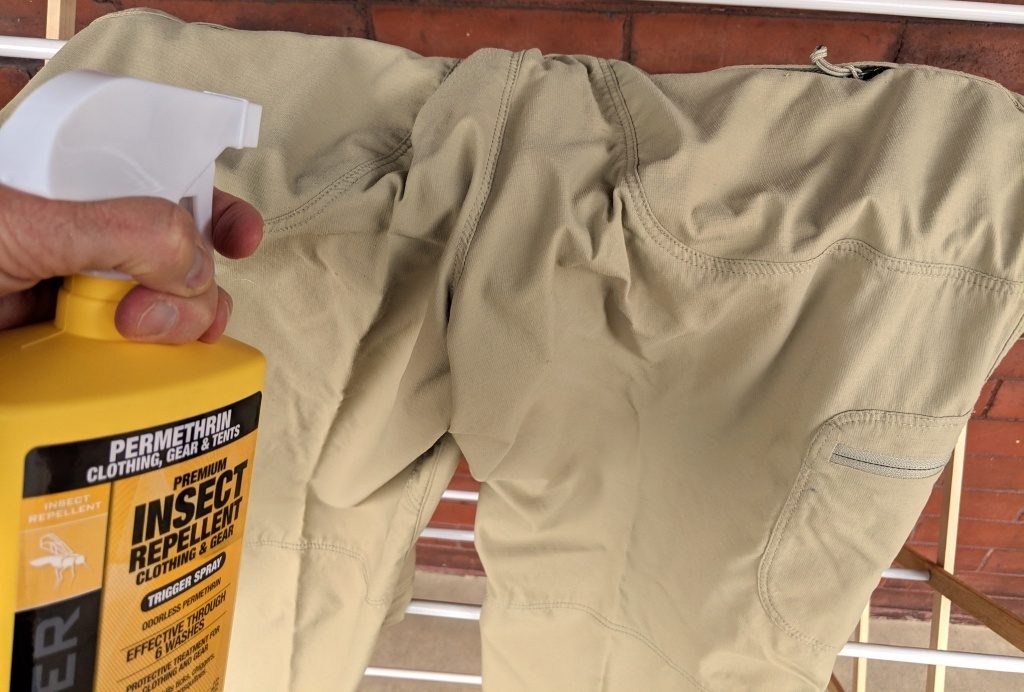

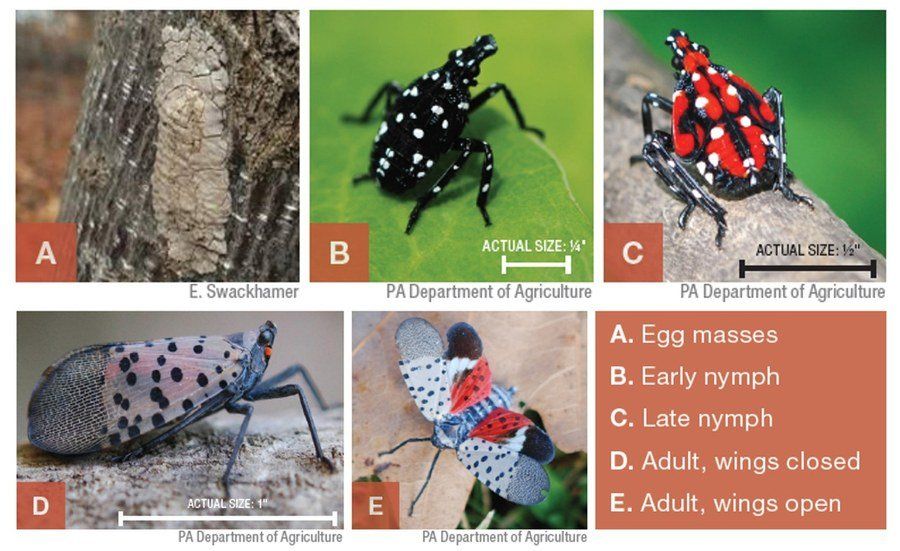

The lanternfly travels easily from September to May as flat gray egg masses on rail cars, trucks and automobiles.

The eggs hatch from spring through summer so now’s the time to watch for black or red spotted nymphs, especially in the unmarked counties above.

If you see spotted lanternflies in any life stage report them at this easy-to-use Penn State Extension website: Have You Seen a Spotted Lanternfly?

We won’t see adult lanternflies until July to November. And frankly, we really don’t want to.

(photos and map from PA Dept of Agriculture, Penn State Extension and Bugwood; click on the captions to see the originals)