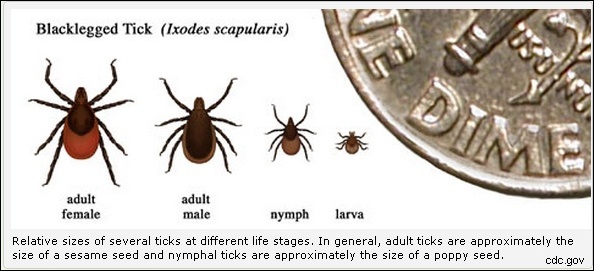

Yesterday damp weeds brushed our clothing as two friends and I walked a creek side trail in the drizzle. When we got back to our cars we checked for black-legged ticks (Ixodes scapularis) and found many on our clothing. I also found one on the car seat where I’d dropped off my backpack and gloves. Yikes!

Black-legged ticks transmit Lyme disease and other bacteria that can ruin your life for a very long time so it’s important to be vigilant about them.

You don’t have to go far to find them. Of course they are in the woods but they’re also found in backyards in Allegheny County. Damp weeds are a favorite habitat. Click on this photo of Japanese barberry to read why.

Needless to say I felt itchy all over after finding the ticks. When I got home I took a careful shower and put all my clothes in a hot dryer for 10+ minutes. Really. Dryers desiccate ticks. In 10 minutes they’re all dead.

Keep yourself safe by following these guidelines –> Forewarned is Forearmed.

Don’t be fooled. Black-legged ticks are still quite active in western Pennsylvania.

(photos from Wikimedia Commons and Kate St. John; click on the captions to see the originals)