8 July 2020

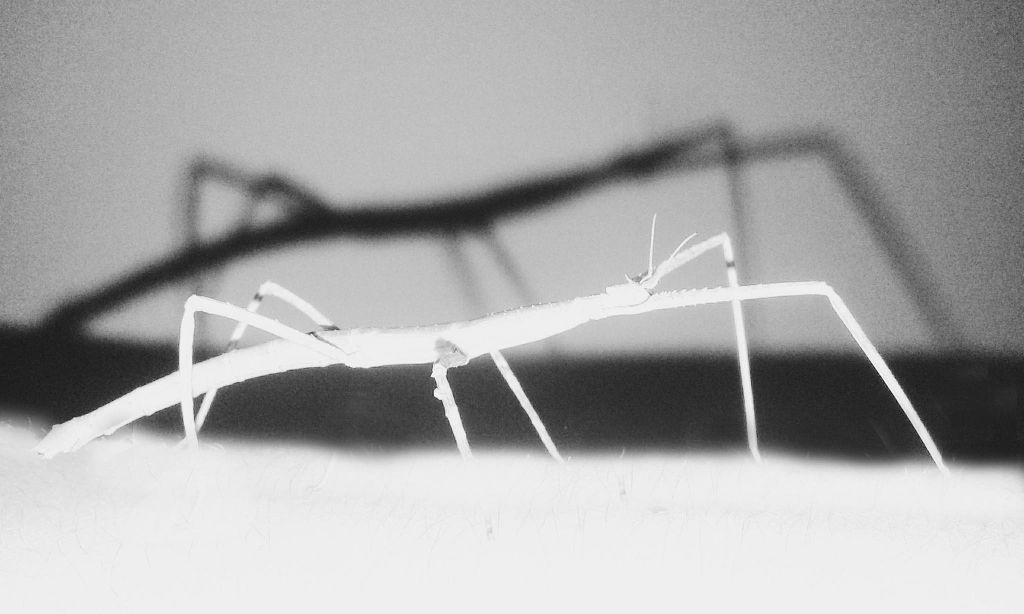

With COVID-19 raging around the world, we humans feel a little less invincible that we did a few months ago. Despite our own fragility there’s a tiny creature, less than 1mm long, that has survived all five mass extinctions. The tardigrade or water bear is practically indestructible.

Tardigrades have a second nickname — moss piglets — because moss and lichen are their favored habitat. Tardigrades don’t care how cold it is. They live in glacier mice and …

… a lot of harsh locations as shown in the video below.

Tardigrades’ only weakness seems to be prolonged heat, so climate change may be bad for them in some places on Earth. However, they’re so versatile and widespread I think most will survive. They are tough little water bears.

p.s. If you missed the blog post on glacier mice, click here to catch up.

(water bear screenshot from the Dodo video above; glacier mouse by cariberry via Flickr)