While in Arizona I went on a night outing to Carr Canyon in hopes of seeing owls. Though we merely heard owls, we saw some amazing bugs. The scarab beetles made the trip worthwhile.

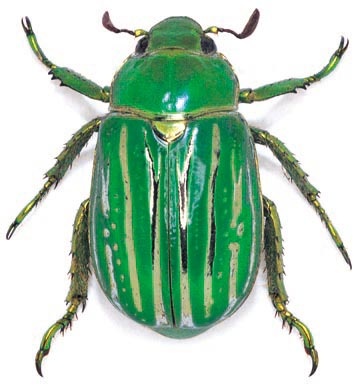

The Glorious scarab (Chrysina gloriosa) was stunning with golden stripes on a green body …

… but my favorite was Beyer’s scarab (Chrysina beyeri) at top, a bright green beetle with violet legs. Notice how big he is!

Their beauty helped me understand why people made jewelry with stones carved like beetles (scarab pin below), but I was wrong to assume that beauty motivated the jewelers.

The original scarab amulets were made in Ancient Egypt. The top of the stone was carved in the shape of the Sacred scarab beetle (Scarabeaus sacer), a symbol of the sun god Ra. The flat bottom was carved with hieroglyphs and used as an impression seal. When mounted on a ring, the scarab was held by a swivel so the seal could be rotated up.

Though an insect was sacred to the Egyptians, the beetle they chose is not a beautiful bug. It symbolized the sun god because, just as the sun rolls across the sky every day, their scarab rolls balls of dung. The Sacred scarab is a plain black dung beetle. Click here to see.

The jewel-like beetles I saw in Arizona live only in the western hemisphere. If the Egyptians could have seen the sunlight colors on the Glorious scarab’s legs and wings, perhaps they would have chosen him instead.

p.s. In Arizona I saw two of four Chrysina beetles that occur in the U.S. The only Arizona Chrysina we missed was LeConte’s (Chrysina lecontei). Yes, LeConte again. 😉

(two photos by Kate St. John, two from Wikimedia Commons. Click on the Wikimedia photos to see the originals)