On Throw Back Thursday (TBT), click here to read about doing the bumblebee dance in this article from 2008.

(photo from Wikimedia Commons. Click on the image to see the original)

On Throw Back Thursday (TBT), click here to read about doing the bumblebee dance in this article from 2008.

(photo from Wikimedia Commons. Click on the image to see the original)

21 April 2015

Yes, it’s time to get outdoors but remember there are dangers out there.

Not bears and mountain lions. I’m talking about deer ticks, also known as black-legged ticks (Ixodes scapularis). They transmit Lyme disease and it can ruin your life for a very long time.

Tick season never ends but it’s really dangerous in the spring and early summer. Most Lyme disease is transmitted in May through July when the deer ticks’ tiny poppy-seed-sized nymphs are active and we’re active too. We don’t notice the nymph, or we forget — or don’t know — the basics of protection against Lyme disease.

Here are the basics with great help from the TickEncounter website at the University of Rhode Island.

I thought I knew about deer ticks but I learned valuable new information at the TickEncounter Resource Center. Visit their website here.

Forewarned is forearmed.

p.s. Even if your clothes are sprayed with permethrin, don’t bushwhack through Bush honeysuckle or Japanese barberry. Those two shrubs are tick magnets!

(photo of clothes and dryer by Kate St. John. tick chart from the Center for Disease Control via Wikimedia Commons. Click on the chart to see the original)

Last Tuesday afternoon the frogs at Raccoon Creek State Park Wildflower Reserve in Beaver County, PA were singing up a storm so I recorded them with my cell phone.

The loud peeps or “crrrreeeep” sounds are spring peepers. The low mutterings or quackings are wood frogs.

There are so many wood frogs in this audio that you can’t hear individuals. There are so few spring peepers that you can hear each one. There might be more species here but I don’t have the ear to hear them.

Check out this list of western Pennsylvania frogs for more possibilities.

(video recorded on March 31, 2015 by Kate St. John)

Have you heard any frogs lately?

In early spring male frogs call from ephemeral pools to attract females to mate with them. This week in Frick Park I’ve heard spring peepers calling in the wetland next to Nine Mile Run. The sound is so miraculous in the City(*) that I always stop to absorb it.

Spring peepers are loud but so tiny I couldn’t find them. Look how small they are compared to someone’s hand! Needless to say I didn’t see the “singers” in Frick Park.

Peepers aren’t the only ones calling. Right now you can hear wood frogs and others if you’re in the right habitat. But which ones?

PA Herps does statewide surveys to confirm the ranges of Pennsylvania’s native frogs (and much more). Based on the PA Herps Frogs and Toads List I made this table of the frogs and toads that still occur in western Pennsylvania west of the Allegheny Front. I added my own description to the calls I know; Sue added all the rest(*) with her comment.

| Frog Name | Description of Call |

|---|---|

| Eastern American Toad, Anaxyrus americanus | a whirring trill |

| Fowler’s Toad, Anaxyrus fowleri | Wraaah or baby balling (*) |

| Cope’s Gray Treefrog, Hyla chrysoscelis | telephone ringing (*) |

| Eastern Gray Treefrog, Hyla versicolor | telephone ringing, slower than Cope’s (*) |

| Bullfrog, Lithobates catesbeianus | a low ‘hrrrrmp’ |

| Green Frog, Lithobates clamitans | a tuneless banjo twang |

| Pickerel Frog, Lithobates palustris | snores (*) |

| Northern Leopard Frog, Lithobates pipiens | creaky door (*) |

| Wood Frog, Lithobates sylvaticus | sounds like ducks quacking |

| Mountain Chorus Frog, Pseudacris brachyphona | fingers across a washboard or rubbing percussion sticks together (*) |

| Northern Spring Peeper, Pseudacris crucifer | LOUD! peeps, jingle bells -or- plinking the teeth of a comb |

| Western Chorus Frog, Pseudacris triseriata | fingers across a comb (*) |

| Eastern Spadefoot, Scaphoipus holbrookii | low-pitched “waah” (*) |

Click here on the PA Herps website to look up each frog including their photos and range map. To hear them, look them up here on the USGS Frog Quiz website. (Your computer must have QuickTime installed.)

If you know a lot of frog calls you can test your skills at the USGS Frog Quiz here. Don’t feel bad if you don’t recognize the calls. I tried the quiz and flunked immediately. It’s time to get outdoors and remedy that!

(*) p.s. The miracle of frogs in Frick Park is a complex of meanders and wetlands completed in 2006 by the Nine Mile Run Watershed Association and U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Spring peepers found the wetlands on their own and now loudly pronounce them good for breeding every spring.

(photo of spring peeper calling by Justin Meissen via Wikimedia Commons. Photo of spring peeper on hand by Fungus Guy via Wikimedia Commons. Click on the captions to see the originals)

Did you know that there’s such a thing as biological immortality? That the mortality rate in some species does not increase with age?

Most plants and animals experience senescence, an age-related functional deterioration that also occurs on the micro scale. Cells progressively lose their ability to divide and grow properly. Humans know all about this.

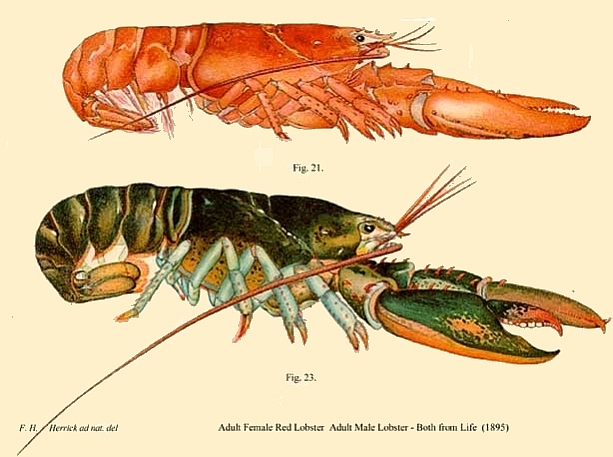

There are some notable exceptions to this rule including hydras, a species of jellyfish, planarian flatworms and lobsters.

Lobsters achieve biological immortality by expressing telomerase through most of their tissue, even as adults. Telomerase is the enzyme that repairs the DNA sequences at the ends of the chromosomes (telomeres) so that when a cell divides it doesn’t lose any information. Human fetuses have telomerase but we don’t have it as adults. Lobsters always have it so they never age.

Despite their immortality, predation or an accident can end a lobster’s life.

Accidents come to mind because …

[Seven years ago] On Tuesday November 25, 2014, just before 4:00pm, my husband was hit by a car while he crossed Murray Avenue in Squirrel Hill. He was in a crosswalk! And the car had a stop sign! He sustained 9 broken ribs on his right side, a broken nose, bruises, a concussion and a partially collapsed right lung. After six days in UPMC Presbyterian Hospital, first in the ICU then in the trauma wing, he came home on 1 Dec 2014 for the long, painful, healing process. Fortunately his injuries were not worse. We are thankful that by May 2015 he had fully recovered. The broken bones healed fast. The concussion took months to heal.

[16 Dec 2021: Seven years later, my husband is fine with no lasting effects.]

In an accident, it doesn’t matter if you’re biologically immortal.

Note: This article was originally published on 2 December 2014, then updated in 2021. Most of the comments were posted in 2014.

(illustration by Francis Hobart Herrick via Wikimedia Commons. Click on the image to see the original)

On Saturday’s blog, red+white made pink. Today, pink makes for roseate names.

The roseate tern has been called the most beautiful tern on earth for his pale rose-colored breast and long fluttering tail streamers. In the photo above, a roseate tern (Sterna dougallii) chases a common tern at Petit Manan Island, Maine. Look closely and you can see the pale pink blush on the tern in the foreground, so pale that the color is not one of its field marks.

The beautiful bird has a good reason for chasing the common one. Roseate terns are listed as endangered in the Northeast and where both species nest, such as Petit Manan, the common terns push out the roseates.

The roseate spoonbill (Platalea ajaja) is a South American bird whose U.S. population was decimated during the plume-hunting era. Now that its carmine, orange, and rose-colored plumes are no longer used for hats, it’s made a modest comeback in Florida and the Gulf Coast states. In Chuck Tague’s photo you can’t see the bird’s orange upper tail but you can see why its name is “roseate.” What a pink bird!

And finally, even a dragonfly can be rose-colored. The roseate skimmer (Orthemis ferruginea) ranges from the southern U.S. to Brazil and has been introduced in Hawaii, perhaps because it’s beautiful. Chuck Tague photographed this one in Florida.

Though their shades of pink are not the same, all three deserve a roseate name.

(Photo of a roseate tern chasing a common tern from US Fish and Wildlife via Wikimedia Commons; click on the image to see the original. Photos of roseate spoonbill and roseate skimmer by Chuck Tague)

Yesterday I mentioned hemlock woolly adelgid, a really bad invasive insect that’s killing our eastern hemlock forests. It devastated the southern Appalachians (click here to see, here to read) and has moved north into south, central and eastern Pennsylvania. Has it conquered the Allegheny High Plateau? Now’s the best time to find out.

Hemlock woolly adelgids (Adelges tsugae) have no North American predators and a very unusual lifestyle. Originally from Japan, they kill eastern hemlocks in 4-20 years by locking onto the underside of their branches and sucking the lifeblood out of them.

The adults are female, immobile and practically microscopic. Twice a year they reproduce asexually, laying up to 300 eggs a year in woolly white egg sacs that protect their young. The larvae, present in April and July, are the only mobile phase and so tiny that they spread easily on the wind or hitchhike unseen on birds, animals and humans.

Harsh winters used to protect Pennsylvania’s hemlocks but the climate is warming. Our worst fears were realized when they were found in Cook Forest in March 2013. Last winter’s Polar Vortex reduced that infection 90-100% but the bugs are poised to take off again. Unfortunately the only biological control, a tiny beetle, is even less winter-hardy than the pest so the only way to save our hemlocks right now is by treating individual trees with pesticide. (*)

What trees should be treated? The Nature Conservancy, the U.S. Forest Service and DCNR have teamed up to survey the area from Cook Forest to New York’s Allegany State Park (click on this map to see a larger version).

It’s a big area and they need your help. Don’t worry, it’s easy.

In the winter hemlock woolly adelgid egg sacs are large and visible (see top photo). If you’re in this region — even for a quick hike or birding trip — take a moment to notice the underside of hemlock branches. Birders, you may accidentally find this while looking at a bird.

Report infections by calling or emailing the location to one of the folks on this list of contacts. (Contact any of them and they’ll forward the information if necessary).

Do you need more information before you begin? Contact Sarah Johnson at The Nature Conservancy, sejohnson@tnc.org, 717-232-6001 Ext 231.

Start looking now.

(photo credits:

top photo, wool sacs: Nicholas Tonelli via Wikimedia Commons

middle photo, adults: Ashley Lamb, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, Bugwood.org

map: courtesy The Nature Conservancy and U.S. Forest Service. Click on the map to see a larger version.)

(*) Note: Work is underway to breed winter-hardy biological controls. It just takes time.

Look at what’s walking on my hand!

On the night before Halloween at Wissahickon Nature Club Sarah Lyle taught us about Pennsylvania spiders and showed us her pet tarantulas. Three of them were very tiny but two were … huge!

I am not a spider lover but Sarah’s enthusiasm for them is infectious. When I first saw her tarantulas I thought, “No way will I handle one of those!” but by the end of the evening I did.

Dianne Machesney, who took this photo, called it “the fearless spider whisperer.”

Not!

My look of concentration is not spider whispering. It’s intent focus on one thought: “Do not do anything to upset this spider!”

Two of the hands in the photo are Sarah’s, gently corralling the tarantula so it doesn’t walk up my arm.

Whew!

(photo by Dianne Machesney)

Yesterday I photographed this half-inch-long moth at Harrison Hills County Park near Natrona Heights.

This morning I tried to identify it at butterfliesandmoths.org using the online photos. I was able to narrow my list to 20 possibilities out of more than 3,000 moths but none of them were correct when I compared closely.

Changing tactics I used the regional perspective: Which of my 20 possibilities were on the Allegheny County moth checklist? The checklist subtracted 10 and added four. However, my faith in that checklist was shattered when I discovered it’s missing Malacosoma americanum, the eastern tentworm moth, that Tom Pawlesh photographed in Allegheny County and posted on the website.

Nonetheless the checklist gave me a hint. Perhaps this is one of the owlet moths, Noctuidae. It looks a bit like the three-spotted sallow moth (Eupsillia tristigmata). Searching through Noctuidae at BugGuide.net I also found one here.

Can you can tell me what moth this is? Please leave a comment with your answer.

UPDATE 25 July 2015: This moth may be the Dotted Sallow moth (Anathix ralla), a member of the Noctuidae family (owlet moths).

(photo by Kate St. John)

p.s. Fascinating news on Monday Oct 27: Owlet moths pollinate witch-hazel flowers at night!

What can you catch in the river in October? The Monster of the Ohio.

On Throw-Back Thursday (TBT), here’s a fish story from October 2008.

(photo from Sam Hall)