We had a fruit fly episode at work last week. We trapped and did not release.

It all began when Emily came back from maternity leave and discovered a co-worker had left old food in her office refrigerator. Emily carefully wrapped up the rotting fruit and threw it away but a couple of fruit flies escaped.

For two days we barely noticed them. A single fruit fly would appear at mealtimes and disappear afterward. By Thursday however the single fruit fly became two and one of them never went away.

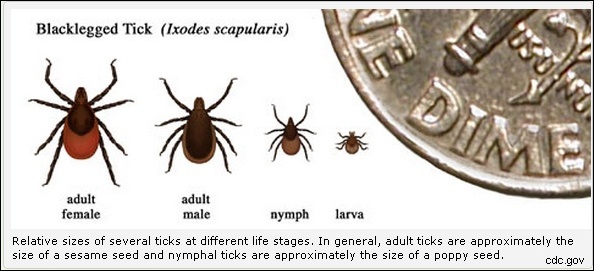

I’m no expert on fruit fly identification but these seemed to be Drosophila melanogaster nicknamed “vinegar flies” because they’re especially attracted to vinegar, a by-product of the rotting fruit which is their favorite food. Here’s a close-up from Wikimedia.

D. melanogaster is well studied. For more than 100 years it’s been the subject of genetic research because its traits are easy to parse out and it reproduces quickly. At warm room temperature (77oF) a newly laid egg becomes a breeding adult in only 8.5 days. The adults live about three weeks during which time the females can lay 100 eggs per day. The D. melanogaster population can quickly get out of hand if you don’t have swallows and flycatchers around to eat them.

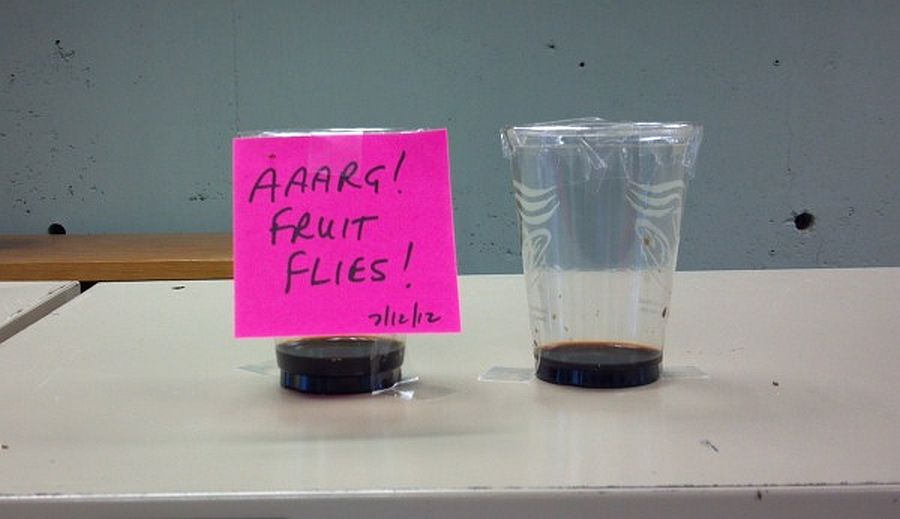

Fortunately Emily knew exactly what to do. She taught us how to make vinegar traps, as in…

- Pour a little vinegar in the bottom of a cup

- Cover the top, leaving only a small hole. We used tape to cover the cups.

- Wait for the flies to fly in and never come out.

Emily supplied the plastic cups. We supplied the tape and vinegar. All we had was balsamic vinegar — very dark.

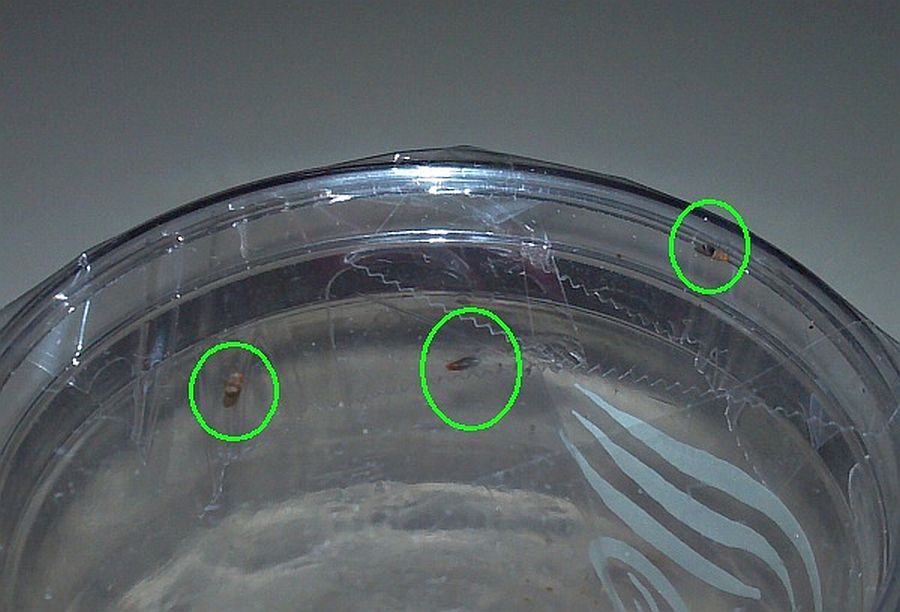

The first photo shows what our traps looked like from the side. The photo below shows them from the top. Because we used tape, the trap hole is a triangle.

My traps caught nothing for hours. Emily’s caught many.

When she left for the day Emily threw away her traps so the next day was quite a success for mine. Using their keen sense of smell, the flies flew further to find the vinegar. In a matter of seconds they could find a new food source down the hallway, the equivalent of a human smelling food and traveling seven miles.

My traps’ success is shown below with three circled fruit flies. And what are those tiny dark specks near the flies? Eggs!

Without birds to eat the flies, vinegar traps will have to do.

(close-up of D. melanogaster from Wikimedia Commons, all other photos by Kate St. John)